Ochikubo v. Bonesteel

A federal lawsuit filed in 1944 in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles challenging the continued mass exclusion of all Americans of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast. When mass exclusion ended in January 1945, the lawsuit shifted to challenge the Western Defense Command 's exclusion of specific individuals. The court resolved the case in the early summer of 1945 on procedural grounds, without deciding the lawfulness of the individual exclusion program.

Background

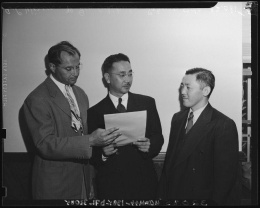

The plaintiff, George Ochikubo, was a Nisei from Oakland, California, born in 1911, who became a dentist before World War II. He and his family were forced from their home into detention at the Tanforan Assembly Center in the spring of 1942 and then at the Central Utah (Topaz) Relocation Center in the fall of 1942. In the summer of 1944, Ochikubo became convinced that there was no longer any military necessity for the continued exclusion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. He retained Los Angeles civil rights attorney A.L. Wirin to file a lawsuit contesting the continued policy of mass exclusion.

Wirin lined up two additional plaintiffs: Ruth Shizuko Shiramizu, the twenty-four-year-old widow of a member of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team , and Masaru Baba, a twenty-six-year-old U.S. Army veteran who had been incarcerated at the Rohwer Relocation Center. Their lawsuit sought a court order barring the military from enforcing the mass exclusion orders that had been implemented in 1942 under the authority of Executive Order 9066 .

The defendant was Major General Charles H. Bonesteel, who as of June 1944 was the Commanding General of the Western Defense Command ("WDC").

Delaying Tactics

The lawsuit, filed in July of 1944, presented difficult problems for the Roosevelt Administration. A central assertion was that mass exclusion of Japanese Americans was no longer militarily necessary. This was a position with which officials at the highest levels of the War Department agreed, but President Roosevelt wished to defer ending mass exclusion until after the November 1944 election. The Justice Department therefore had to find a way to prevent consideration of the case or delay it until after the election.

The Justice Department first suggested blocking consideration of the case entirely by granting Ochikubo, Shiramizu, and Baba permission to return to the West Coast. This would have had the effect of mooting the lawsuit, and would have required the courts to dismiss it. Major General Bonesteel was willing to grant such permission to Shiramizu and Baba, and did so in August of 1944, but refused in Ochikubo's case, believing him, notwithstanding the War Relocation Authority's contrary finding, to "possess[ ] the qualities and connections essential to an enemy agent." Justice Department lawyers therefore had no other choice but to file various motions in court in an attempt to put off the moment when they would need to file a response defending the mass exclusion program that they knew the government no longer believed necessary. John Burling, a Justice Department attorney who opposed this strategy of throwing up procedural impediments to the litigation, charged in an internal memorandum that this amounted to nothing more than "stalling on bad faith procedural tactics."

In September of 1944, Wirin was able to force the hand of the Justice Department and require it to reveal its grounds for defending mass exclusion. Rather than do this, the government decided to issue an order for Ochikubo's individual (as opposed to mass) exclusion. This move had the effect of converting Ochikubo's lawsuit from a test of the validity of mass exclusion to a test of the validity of continuing to keep Ochikubo himself out.

Trial and Outcome

Trial of Ochikubo v. Bonesteel began on February 27, 1945, before Federal District Court Judge Pierson M. Hall in Los Angeles. Three issues were before the court: Did the military situation along the West Coast still require the exclusion from the WDC of some Nisei? Did the WDC have a valid mechanism in place to decide who was too dangerous to be allowed to return to the coast? And was the determination that Ochikubo was too dangerous impermissibly arbitrary?

On each of these points, military witnesses from the WDC distorted the truth in order to try to secure from the court a broad declaration that the military had virtually limitless power to control civilians. Contrary to all military intelligence data, a WDC witness testified that the military risk that Japan posed to the West Coast in early 1945 remained high and that the danger of sabotage and espionage by Japanese Americans was actually increasing rather than decreasing, if only because of the known Japanese penchant for "face-saving" behavior in the teeth of defeat. More disturbingly, another witness from the WDC testified that the process for deciding who should be individually excluded was loose, highly discretionary, and dependent on daily shifts in the military security situation along the coast, when in fact the process was a rigid, simplistic, and unvarying inquiry into whether a particular individual possessed one of a few listed disqualifying attributes, such as having requested expatriation to Japan. Most disturbingly of all, under the WDC's actual system, George Ochikubo presented none of the disqualifying attributes, and should not have been excluded.

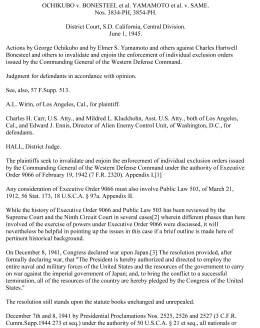

Federal district judge Hall decided the case in June of 1945 on grounds that had no relationship to the testimony that had been adduced in court. He held that because Congress had passed a criminal law making it a civilian crime to disobey a military exclusion order authorized by Executive Order 9066, the commanding general of the WDC did not have the power to enforce an order excluding someone like Ochikubo; the most he could do if an excluded person returned to the coast was refer the matter to the Justice Department for criminal prosecution. As a result, Ochikubo was suing to prevent the commanding general of the WDC from taking an action that the law did not allow him to take, and the suit was groundless.

Although Ochikubo v. Bonesteel did not end up producing a decision on the validity of the individual exclusion of George Ochikubo, it is noteworthy for the lengths to which military witnesses and Justice Department lawyers were willing to go in order to try to get a court to declare that military officials have nearly unreviewable power to control civilians during wartime.

For More Information

Muller, Eric L. American Inquisition: The Hunt for Japanese American Disloyalty in World War II . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Ochikubo v. Bonesteel, Federal Supplement, vol. 60, p. 916 (U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, 1945). Accessible online at http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=118331013469824771&hl=en&as_sdt=2&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr .

Last updated June 15, 2020, 7:03 p.m..

Media

Media