Return to West Coast

The exclusion of "loyal" Japanese Americans from the West Coast states ended on January 2, 1945, delayed for months until the after the 1944 presidential election due to continued opposition from those states. Early returnees faced stiff opposition and even physical violence that dissipated slowly over time. Returnees to urban areas faced severe housing and job shortages. Though the Japanese American population on the West Coast had nearly returned to prewar levels by 1950, it was a very different community than it had been before.

Ending Exclusion

As allied forces made headway against Japan in the Pacific—and as the War Relocation Authority ushered "loyal" incarcerees from its camps to points east and Japanese American soldiers entered into battle in Europe in mid-1943—the War Department was coming to believe that there no longer was a "military necessity" to exclude Japanese Americans from the West Coast. However General John L. DeWitt and the Western Defense Command (WDC) continued to insist that this was not in fact the case. Speaking before a house committee on April 13, 1943, DeWitt stated, "There is a feeling developing, I think, in certain sections of the country, that the Japanese should be allowed to return. I am opposing it with every proper means at my disposal." [1]

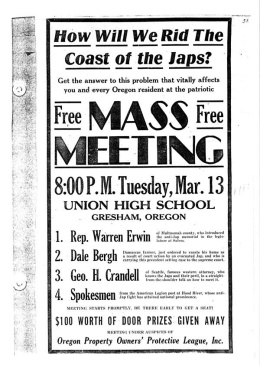

Despite the fact that the West Coast had been cleansed of Japanese Americans—save for those in concentration camps—anti-Japanese agitation began to rise in 1943 for various reasons, including the WRA's institution of its leave program, stories of unrest in the camps and of inmates being "coddled," and reports of Japanese barbarism in the Pacific. Old anti-Japanese groups were reinvigorated and new ones formed, calling for a constitutional amendment to strip all Japanese Americans of citizenship, expanding alien land laws , deporting Issei , and preventing Nikkei from returning to the West Coast. The Hood River County Sun ran a poll in January 1943 in which 84% of respondents would not allow any Japanese Americans to return after the war. A Los Angeles Times survey published in December 1943 found that 9,855 respondents favoring the permanent exclusion of Japanese from the Pacific Coast states to 999 opposed. [2]

Despite the opposition of the WDC and West Coast public and political leaders, steps toward opening the West Coast took place. In April of 1943, Gen. DeWitt acceded to allowing Nisei soldiers to return while on furlough. By the spring of 1944, the Departments of War, Interior, and Justice were all ready to recommend the ending of exclusion. New WDC head Delos Emmons (who had replaced DeWitt in September 1943) began issuing individual exemptions, leading to over 1,400 Japanese Americans returning by the end of 1944. Emmons' successor, Charles Bonesteel, advocated ending exclusion by the summer of 1944 and even the navy agreed by September. Administration officials also knew that pending legal decisions in the Shiramizu, Ochikubo , and Endo cases would very likely throw open the gates to the concentration camps. But the ultimate decision rested with President Franklin D. Roosevelt , who decreed that any action on this matter would have to wait until after the election in November. In the first cabinet meeting after the election, the decision to lift the exclusion was made. Public Proclamation Number 21 was issued on December 17, 1944, rescinding the exclusion orders, with individual exclusion orders taking their place. Most Japanese Americans would be free to return as of January 2, 1945.

The First Returnees and Anti-Japanese Agitation

The first to return after the opening of the West Coast largely fell into two overlapping categories. The first were the fortunate minority who had homes, farms, or businesses to return to. The second group were what WRA community analysts called "scouts," those who went to explore the climate—housing and job possibilities, the attitudes of the locals, the general sense of what returning would be like—before returning to camp to report back to the camp community before making their final decision. [3]

The first scouts undoubtedly reported on a mixed bag. Well-publicized discriminatory and terrorist actions greeted many returnees. The two most highly publicized were the removal of Nisei soldiers' names from a veterans' monument in Hood River, Oregon, and the attempted dynamiting and burning down of a packing shed of a returning family in Placer County, California. (See Hood River Incident and Terrorist Incidents Against West Coast Returnees .) Some twenty episodes of shots fired into homes of returnees, along with dozens of incidents of arson, terroristic threats, and vandalism greeting those bold enough to return. Yet more anti-Japanese organizations formed or expanded in the early months of 1945: the Japanese Exclusion League in Bellevue, Washington; the California Preservation Association in Placer County, California; and the Remember Pearl Harbor League in Seattle were but a few. Reports of these incidents reached the camps and further discouraged those reluctant to leave. [3]

At the same time, the vast majority did return largely without serious incident. Many who owned land and farms were able to reclaim their property, though they often found things missing and the properties vandalized or in poor repair. A few had been able to organize caretakers to watch over their property. The residents of the agricultural colonies of Livingston, Cressy, and Cortez, California, had been able to arrange for the wartime management of their farms by a white organization and were able to return as communities. The owners of the California Flower Market in San Francisco had also arranged for caretakers and were able to return to a functioning organization. The WRA had also established around twenty-five district offices in communities along the West Coast to help with resettlement. [4]

But the anti-Japanese agitation was short lived for the most part. While many local officials railed against the return of the Nikkei, most state and federal officials—including those who once pushed for exclusion such as California Governor Earl Warren —preached tolerance, or least obeying the law. Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron , who had opposed the return of the Nikkei two years prior, held a public ceremony welcoming them back. [5] Many individuals spoke out and provided assistance to returnees. The exemplary military record of the Japanese American soldiers also helped turn public opinion, and white soldiers who had served with Nisei often spoke out against the agitation upon their return. The changing demographics of the West—large numbers of African Americans and other ethnic minority groups had migrated to California during the war—and comparisons with Nazi Germany no doubt also led to the shift in public opinion.

Return to Rural Communities

Those who returned to rural areas versus urban areas faced a different set of issues and opportunities. Prior to the war, the population had been heavily rural, with farming serving as the economic backbone of the ethnic economy. But circumstances related to the war years contributed to a shift from agriculture. Whereas over 40% of Japanese Americans worked in agriculture in 1940, the number dropped to 32.5% in 1950, then to 20.9% by 1960. [6]

While a quarter of Japanese American farmers had property to which they could return to after the war, the rest faced difficult obstacles to returning. [7] For one thing, discrimination in rural areas—as evidenced by the preponderance of overt agitation and terrorist incidents taking place there—seemed more intense than in urban areas. Land to purchase or lease was hard to come by, and the war had wiped out capital reserves necessary to acquire the land anyway. Beyond discrimination, many Japanese Americans returned to find that land they had leased was now slated for new shopping centers or suburban developments or had seen land prices rise due to such changes in land use. [8] Alien land laws were still on the books, and the state of Oregon actually passed a harsher law in March of 1945. As a result, many prewar farmers without farms to return to were relegated to manual labor. As one Nisei returnee reported, "I am doing the kind of work I haven't done for 15 to 20 years before evacuation. I used to hire other men to do it for me. But I'm not proud. I'll do anything that comes along." [9]

Even those farmers who had property to return to faced difficulties. Movements to boycott the purchase and marketing of "Japanese" produce sprang up in some places. A new wave of escheat cases —legal proceedings to repossess land "illegally" owned under the dictates of alien land laws—were brought by the states to further harass returning farmers throughout the West Coast. And many businesses in farm communities refused to sell to returning Nikkei.

Return to Urban Areas

Those returning to urban areas faced a different set of issues, most of them centering on the lack of housing and jobs. Those who returned to cities found them very different places than the ones they had left, given the wartime influx of large numbers of workers drawn by war industries. The "vacancies" created in the former Japanese towns were soon filled with war workers, many of them African American. Little Tokyo in Los Angeles became known as "Bronzeville" and African Americans gravitated to the former Japantown in San Francisco as well. Housing in other parts of town was scarce, and restrictive covenants and housing discrimination reigned.

To help ease the housing shortage, both non-governmental and governmental facilities were opened. Most of the non-governmental hostels were in former Buddhist temple properties. A hostel association formed in Los Angeles and established uniform rates that went up after a ten-day stay. One returnee to San Francisco recalled, "We slept at the Buddhist church auditorium where they had just rows and rows of cots for single men. Married couples slept on the balcony. They had army blankets for partitions. We stayed there until someone threw a rock into the window and they felt it was too dangerous." She added, "The snoring resembled an orchestra tuning up." [10]

But when it became clear that further assistance would be needed, the WRA worked with the Federal Public Housing Authority (FPHA) to use former army facilities as emergency housing for returning Nikkei in urban areas. In the Sacramento area, the WRA obtained use of army barracks at Camp Kohler in November 1945; ironically, this was the same facility that had been the Sacramento Assembly Center three-and-a-half years prior. In Southern California, returnees lived in barracks and trailers in Burbank, Santa Ana, Lomita, Hawthorne, El Segundo, Santa Monica, and Long Beach run by the FPHA. Most of these facilities were closed down by the middle of 1946, with special trailer parks in Burbank and Sun Valley remaining open for "hardship cases." These two facilities—each consisting of about 100 trailers that residents could purchase—remained open for many years after the war, with the Burbank facility closing in 1948 and Sun Valley in 1956. [11]

Closely related to the search for housing was the search for jobs. The ethnic economy that had sustained the community before the war was largely gone, and most former business owners lacked the capital to start new businesses. So large numbers of Japanese Americans took work as domestics, janitors, or caretakers. Some of these jobs were doubly appealing because they also came with live-in housing arrangements. But this sometimes resulted in the dispersion of families where different family members lived and worked in different places. But as a short-term solution, the good wages and low expenses provided a boost to many returned Japanese Americans.

As a business that required little capital—and one that Japanese Americans had established a positive reputation in—gardening became a large occupational niche for others. As time went on, civil service and other jobs that had been closed to Japanese Americans began to open up. Many Nikkei who did have capital purchased residential hotels and apartments since they offered both housing and income, driving up prices of these properties tenfold from what many had been forced to sell them for upon removal in 1942. The high rents Nikkei hotel owners passed on to their tenants—and the often overcrowded conditions in the hotels—led to charges that they where exploiting their co-ethnics. [12]

Residual Effects

The largely gloomy picture of the immediate return to the West Coast eased for many over the next decade. Japanese Americans were among those caught in larger trends such as the postwar economic boom and the easing in race relations inspired by the Cold War. Inspired by the wide publicity of the heroic exploits of Japanese American soldiers, the image of Japanese Americans changed, and many of the discriminatory laws that had once ruled—including bans on naturalization, alien land laws, and restrictive housing covenants—were turned back. In fact, before long, Japanese Americans had a new image as a " model minority "; however, that image ignored the many—particularly Issei—who would never recover from the upsets of wartime.

While many Japanese Americans had left the incarceration camps for resettlement in the mountain states, Midwest, or East during the war, many began to come back to the coast after the war. By 1950, the Nikkei population on the West Coast was well over 80% of what it had been before the war. But that community was different in many ways—more urban and more decentralized within urban areas, as Little Tokyos were replaced or augmented by suburban residential clusters. Many Issei were now dependent on Nisei in multiple generation households that were centered on a new generation of Sansei children. Many Japanese Americans recalled going out of their way to keep a low profile. (See psychological effects of the camps .) Incarceration had not killed Japanese American communities—and Japanese American identity—but it had changed it in ways that wouldn't be understood for many years.

For More Information

General

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians . Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1982. Foreword by Tetsuden Kashima. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997.

Daniels, Roger. Asian America: Chinese and Japanese in the United States since 1850 . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988.

Dempster, Brian Komei. Making Home from War: Stories of Japanese American Exile and Resettlement . Berkeley, Calif. Heydey Books, 2010.

Girdner, Audrie, and Anne Loftis. The Great Betrayal: The Evacuation of the Japanese-Americans during World War II . Toronto: Macmillan, 1969.

Spicer, Edward H., Asael T. Hansen, Katharine Luomala, and Marvin K. Opler. Impounded People: Japanese Americans in the Relocation Centers . Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Interior, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1946. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1969.

Impact on Specific Communities

Brooks, Charlotte. Alien Neighbors, Foreign Friends: Asian Americans, Housing, and the Transformation of Urban California . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Cole, Cheryl L. A History of the Japanese Community in Sacramento, 1883-1972: Organizations, Businesses and Generational Response to Majority Domination and Stereotypes . San Francisco: R & E Research Associates, 1975.

deGuzman, Jean-Paul. "'And Make the San Fernando Valley My Home': Contested Spaces, Identities and Activism on the Edge of Los Angeles." Ph.D dissertation, UCLA, 2014.

———. "Race, Community, and Activism in Greater Los Angeles: Japanese Americans, African Americans, and the Contested Spaces of Southern California." In The Nation and Its Peoples: Citizens, Denizens, and Migrants . Edited by John S.W. Park and Shannon Gleeson. New York: Routledge, 2014. 29–48.

Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California. Nanka Nikkei Voices: Resettlement Years, 1945–1955 . Torrance, CA: Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California, 1998.

Kurashige, Scott. The Shifting Grounds of Race: Black and Japanese Americans in the Making of Multiethnic Los Angeles . Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

Leonard, Kevin Allen. "'Is That What We Fought For'? Japanese Americans and Racism in California, the Impact of World War II." Western Historical Quarterly 21.4 (Nov. 1990): 463-82.

———. The Battle for Los Angeles: Racial Ideology and World War II . Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2006.

Maeda, Wayne. Changing Dreams and Treasured Memories: A Story of Japanese Americans in the Sacramento Region . Sacramento: Sacramento Japanese American Citizens League, 2000.

Matsumoto, Valerie J. Farming the Home Place: A Japanese American Community in California, 1919-1982 . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993.

———. City Girls: The Nisei Social World in Los Angeles, 1920–1950 . New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Modell, John. "The Japanese of Los Angeles: A Study in Growth and Accommodation, 1900-1946." Diss., Columbia University, 1969.

Neiwert, David. Strawberry Days: How Internment Destroyed a Japanese American Community . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Robinson, Greg. After Camp: Portraits in Midcentury Japanese American Life and Politics . Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

Tamura, Linda. The Hood River Issei: An Oral History of Japanese Settlers in Oregon's Hood River Valley . Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

Taylor, Sandra C. Jewel of the Desert: Japanese American Internment at Topaz . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Footnotes

- ↑ Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1982; Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997), 221.

- ↑ Kevin Allen Leonard, The Battle for Los Angeles: Racial Ideology and World War II (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2006), 223–25.

-

↑

3.0

3.1

Robert F. Spencer, et al.,

Impounded People: Japanese Americans in the Relocation Centers

(Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Interior, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1946; Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1969), 259.

Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "ftnt_ref3" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Valerie J. Matsumoto, Farming the Home Place: A Japanese American Community in California, 1919-1982 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993), 155–57; Gary Kawaguchi, Living with Flowers: The California Flower Market History (San Francisco: California Flower Market, 1993), 58–63.

- ↑ Roger Daniels, Asian America: Chinese and Japanese in the United States since 1850 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988), 292; Leonard, Battle for Los Angeles , 249–50.

- ↑ Daniels, Asian Americans , 289–90.

- ↑ Matsumoto, Farming the Home Place , 157.

- ↑ See for instance, Neiwert, Strawberry Days , 215–16 and Wayne Maeda, Changing Dreams and Treasured Memories: A Story of Japanese Americans in the Sacramento Region (Sacramento: Sacramento Japanese American Citizens League, 2000), 208.

- ↑ Spicer, et al., The Impounded People , 289.

- ↑ Pacific Citizen , July 28, 1945, 8; Sandra C. Taylor, Jewel of the Desert: Japanese American Internment at Topaz (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 278.

- ↑ WRA: A Story of Human Conservation (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Interior, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1946), 152; Cheryl L. Cole, A History of the Japanese Community in Sacramento, 1883-1972: Organizations, Businesses and Generational Response to Majority Domination and Stereotypes (San Francisco: R & E Research Associates, 1975), 66; Pacific Citizen , Oct. 13, 1945, 3; Nov. 3, 1945, 8; Nov. 10, 1945, 2; Nov. 17, 1945, 3; Mark Igler, "Both Fond, Bitter Memories: Post-War Trailer Park Refugees Plan Reunion," Los Angeles Times , Jun. 5, 1986.

- ↑ Charlotte Brooks, Alien Neighbors, Foreign Friends: Asian Americans, Housing, and the Transformation of Urban California (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.), 167–68.

Last updated Oct. 8, 2020, 3 p.m..

Media

Media