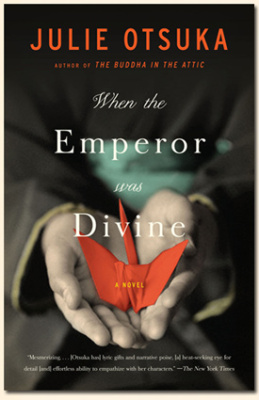

When the Emperor Was Divine (book)

| Title | When the Emperor Was Divine |

|---|---|

| Genre | Fiction |

| Author | Julie Otsuka |

| Original Publisher | Knopf |

| Original Publication Date | 2002 |

| Pages | 144 |

| WorldCat Link | https://www.worldcat.org/title/when-the-emperor-was-divine-a-novel/oclc/978251525 |

Short novel centering on the forced removal and incarceration of a Japanese American family from Berkeley, California, in 1942 and their return to their home after the war. Praised for its spare yet detailed and poignant text that tells each section of the story from the perspective of a different character, the novel received numerous and positive reviews. Educators in particular embraced the book in part for its relevance in the aftermath of the 9/11 tragedy and fallout. The book has been translated into six languages and has sold more than 250,000 copies.

Book and Author Overview

Julie Otsuka was born on June 15, 1962, in Palo Alto, California, the eldest of three children born to an aerospace engineer father and lab technician mother. When she was nine, the family moved to Palos Verdes, California, an upscale suburb of Los Angeles. Otsuka excelled in school and was accepted to Yale University where studied sculpture and painting, graduating with a degree in art in 1984. Over the next several years, she pursued a career as a painter, first in New Haven, then entering an M.F.A. program at the University of Indiana, then in New York City, ultimately giving up in 1990 at age 27. She spent the next three years going to a cafe to read and eventually write, supporting herself doing word processing in the evenings. She entered Colombia's MFA program in 1994, eventually graduating in June 1999.

While at Columbia, she began what would become When the Emperor Was Divine . She told William Nakayama "The first chapter of the novel started as a story that I wrote at Columbia. It literally seemed to come out of nowhere. I had never written about the war before. I'd never written a serious voice before. It was very uncharacteristic of me to write in that way and about that subject." [1] Two chapters were published in anthology that was eventually read by well known literary agent Nicole Aragi, who took her on as a client. Her master's thesis included two-and-a-half chapters of the book. When Aragi sent the finished manuscript to an editor at Knopf on a Friday, the editor called back the following Monday wanting to buy it. The book was published in September 2002. [2]

The novel was loosely based on the experience of the author's mother's family whose members were the same age as the characters in the book and were taken to the same camps. It tells the story of an unnamed family of four—"the woman," a 41 year old mother of two, "the girl," who is ten when the story begins, and "the boy" who is seven—from the posting of the " evacuation order " to their return to their home after the war. When the narrative begins, the father had already been taken away on the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor to be held in a variety of detention camps away from his family. The book consists of five chapters, each told from the perspective of a different character: "Evacuation Order No. 19," on the preparations for "evacuation" is told through the eyes of the mother; "Train," on the journey from Tanforan "Assembly Center" to Topaz, from the perspective of the daughter; "When the Emperor Was Divine," on their time at Topaz , from the perspective of the son; and "In a Stranger's Backyard" from the perspective of both children. The brief final chapter, "Confession" is an angry and satirical rant by the father. The family had been quite privileged before the war, with the father having been a successful businessman, and the family lived in a nice home in Berkeley "not too far from the ocean." When they return to the home after the war , it has been vandalized. All dream of being reunited throughout their incarceration and letters to between the man and his family are frequent. However, the reunion never does come in camp, and when he finally comes home to Berkeley, he is no longer the same person, never going back to work and staying in his room staring out the window.

Reaction and Impact

The book received almost universally positive reviews. Influential New York Times reviewer Michiko Kakutani set the tone, writing that "Ms. Otsuka's precise but poetic evocation of the ordinary ... lends this slender novel its mesmerizing power" and praising Otsuka's "lyric gifts and narrative poise, her heat-seeking eye for detail, her effortless ability to empathize with her characters." Similar reviews followed in such publications as The New Yorker ("Otsuka's incantatory, unsentimental prose is the book's greatest strength"), Los Angeles Times , Times Literary Supplement (UK) and many other magazines, newspapers, and journals. [3] Some reviewers thought the prose too distant to be affecting and some, including Kakutani, were critical of the final chapter, which differs in tone greatly from the rest of the book. [4]

The book also struck a chord with educators, who saw the book as an ideal educational vehicle in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks and the questions about civil liberties in times of war that emerged. As noted by New York Times education writer Samuel G. Freedman, "What has happened with 'Emperor' is what no one in publishing or education can predict: the way an accomplished work of art, though set in the past, captures something essential about the present day." Freedman went on to compare the impact of the book to the debuts for Lord of the Flies or To Kill a Mockingbird , books that remain staples of high school curricula. [5] It has been chosen for freshman read-type programs (where all incoming freshman read the book) at over 35 colleges and universities and became a selection of both Barnes and Nobles "Discover Great New Writers" and Border's "Original Voices" programs. It was also one of the ten recipients of the 2003 Alex Award by the Young Adult Library Services Association, awarded to adult books with particular appeal to young adult readers. Otsuka's website reports that the book has been translated into six languages and has sold more than 250,000 copies. [6]

Otsuka's second novel, The Buddha in the Attic , about a group of picture brides , was released to great acclaim in 2011.

Might also like: The Legend of Fire Horse Woman by Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston; The Red Kimono by Jan Morrill; After the Bloom by Leslie Shimotakahara

For More Information

Otsuka, Julie. When the Emperor Was Divine: A Novel. New York: Knopf, 2002.

Julie Otsuka website: https://www.julieotsuka.com/copy-of-the-swimmers .

Freedman, Samuel G. "On Education: One Family's Story of Persecution Resonates in the Post-9/11 World." New York Times , August 17, 2005, 9.

Fugikawa, Laura Sachiko. "Domestic Containment: Japanese Americans, Native Americans, and the Cultural Politics of Relocation." Ph.D dissertation, University of Southern California, 2011.

Hong Sohn, Stephen. "These Desert Places: Tourism, the American West, and the Afterlife of Regionalism in Julie Otsuka's When the Emperor Was Divine." Modern Fiction Studies 55.1 (Spring 2009): 163–88.

Kawano, Kelley. "Bold Type: A Conversation with Julie Otsuka." http://www.randomhouse.com/boldtype/0902/otsuka/interview.html .

Manzella, Abigail Genee Hughes. "Permanent Transients: The Temporary Spaces of Internal Migration in Four 20th-Century Novels by U.S. Women Writers." Ph.D. dissertation, Tufts University, 2010.

Morishima, Emily Hiramatsu. "Remembering the Internment in Post-World War II Japanese American Fiction." Ph.D. dissertation, UCLA, 2010.

Nakayama, William. "Simmering Perfection." Goldsea.com. http://goldsea.com/Personalities/Otsukaj/otsukaj.html .

Park, Josephine. "Alien Enemies in Julie Otsuka's When the Emperor Was Divine ." MFS Modern Fiction Studies 59.1 (Spring 2013): 135–55.

Shea, Renee H. "The Urgency of Knowing." Poets & Writers 39.5 (Sept./Oct. 2011): 50–56.

Trachtenberg, Peter. Anchor Books Teacher's Guide to When the Emperor Was Divine . New York: Anchor Books, 2003. https://www.randomhouse.com/catalog/teachers_guides/9780385721813.pdf .

Wong, Gary Sasaki. "Sansei Internment Camp Literature and Guilt from Secondary Victimization." M.A. thesis, San José State University, 2010.

Footnotes

- ↑ William Nakayama, "Simmering Perfection." Goldsea.com. http://goldsea.com/Personalities/Otsukaj/otsukaj.html , accessed October 14, 2012.

- ↑ Author and book background from Samuel G. Freedman, "On Education: One Family's Story of Persecution Resonates in the Post-9/11 World," New York Times , August 17, 2005, 9; Kelley Kawano, "Bold Type: A Conversation with Julie Otsuka," http://www.randomhouse.com/boldtype/0902/otsuka/interview.html ; and Nakayama, "Simmering Perfection."

- ↑ Michiko Kakutani, "Books of the Times: War's Outcasts Dream of Small Pleasures." New York Times , Sept. 10, 2002, http://www.nytimes.com/2002/09/10/books/books-of-the-times-war-s-outcasts-dream-of-small-pleasures.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm ; "Books Briefly Noted," The New Yorker , October 28, 2002, http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2002/10/28/021028crbn_brieflynoted , both accessed on October 14, 2012.

- ↑ For instance, Sylvia Santiago "When the Emperor Was Divine (Book)," Herizons 17.3 (Winter 2004): 37-38, Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost and "When the Emperor Was Divine (Book)," Kirkus Reviews 70.15 (August 2002): 1068, Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost , both accessed October 14, 2012.

- ↑ Freedman, "On Education."

- ↑ Charlotte Abbott, "Paperback Comebacks," Publishers Weekly 250.12 (March 24, 2003): 19, Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost ; 2003 Alex Award Winners, http://www.ala.org/yalsa/booklistsawards/bookawards/alexawards/annotations/2003alexawards ; http://www.julieotsuka.com/about/ , all accessed October 14, 2012).

Last updated Dec. 15, 2023, 6:43 a.m..

Media

Media