Yasui v. United States

The content in this article is still under development. A completed version will appear soon!

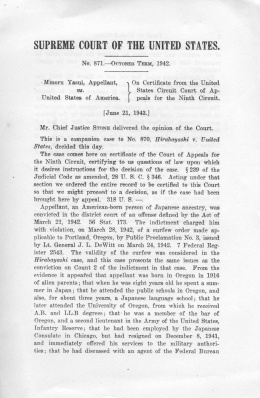

Minoru Yasui v. United States was one four cases challenging aspects of Japanese American exclusion and detention to reach the U.S. Supreme Court. Yasui's challenge of the curfew applied to Japanese American citizens was the first test by any Japanese American of wartime restrictions against them. Found guilty initially, the Supreme Court upheld his conviction and the legality of the curfew.

The case originated in Portland, Oregon, where Yasui was a young Nisei lawyer. Unable to find a legal position before the war, he had been working for the Japanese consulate in Chicago at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, immediately resigning his position and returning to Portland after Dec. 7, 1941 . Angered by Executive Order 9066 , he discussed mounting a test case with legal colleagues, including prominent Portland attorney Earl Bernard, who reminded him that he could only test the law by violating it. He also kept in touch with local U.S. Attorney Carl Donaugh, letting him know he would be launching a test case. Yasui decided to challenge the first restriction aimed at Japanese Americans, not necessarily waiting for exclusion. He also searched in vain for the ideal test case subject, finally resigning himself to being that subject, despite his being far from ideal due to his father's internment and his own work with the Japanese consulate.

On March 24, General John DeWitt announced an 8 pm to 6 am curfew for enemy aliens and for Japanese American citizens. When the curfew went into effect on March 28, Yasui had himself arrested. (He was not bailed out until two days later by Bernard, who had agreed to represent him, not realizing that anyone arrested on a weekend had to spend the weekend in the drunk tank until Monday morning.) When the exclusion order was issued for Portland, Yasui ignored it, and drove to his family home in Hood River. MPs were eventually dispatched to escort him from Hood River to the Portland Assembly Center . The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) both declined to assist him, the former steering clear because of his prior connection with the Japanese consulate, the latter opposing all dissent at that time. (In a JACL publication, executive secretary Mike Masaoka referred to Yasui and other legal challengers as "self-styled martyrs who are willing to be jailed in order that they might fight for the rights of citizenship.")

His trial took place on June 12, 1942, before District Court Judge Alger Fee. Yasui had waived his right to a jury trial, preferring a judge decide the case. The trial lasted the full day, with the prosecution focusing its efforts on his consulate job and trying to question his loyalties. He was escorted back to the Portland Assembly Center after the trial, where he remained through the summer and after being transferred to Minidoka along with the other Portland inmates. Finally, on November 14, a U.S. marshal came to Minidoka to escort him back to Portland for the verdict.

Judge Fee's verdict first argued that without martial law, the military had no right to treat Nisei any differently that other American citizens. However, he then argued that Yasui's employment at the consulate had effectively resulted in his forfeiting his U.S. citizenship and thus found him guilty. He was sentenced to the maximum penalty of one year in jail and a fine of $5,000. He was held at the Multnomah County Jail in solitary confinement, ostensibly for his own protection, allowed no exercise periods, no showers, or haircuts. He and Bernard immediately decided to appeal.

The appeal took place five months later, before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco, together with the appeals for the Hirabayashi and Korematsu cases. Under the influence of Edward Ennis of the Justice Department, the appeals court invoked certification—essentially declining to rule and asking a higher court to rule on the case—to send the case directly to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court heard the case—along with that of Gordon Hirabayashi —on May 10 and 11, 1943. Before the Supreme Court, Bernard was joined by A. L. Wirin of the Southern California office of the ACLU, which did eventually decide to participate in the case. The government acknowledged that Judge Fee had erred arguing that Yasui's consulate employment had been a renunciation of citizenship. Solicitor General Charles Fahy argued that the military should have the discretion to determine military necessity and that Japanese American "racial characteristics" made it reasonable to exclude them. The court issued a unanimous ruling on June 21, 1943, upholding Yasui's conviction and the legality of the curfew and sent the case back to Fee for sentencing. Fee considered the nine months Yasui had already served as sufficient and suspended the fine. On August 19, 1943, he was "released" from prison, to be escorted by a U.S. marshal back to the American concentration camp at Minidoka.

In the 1980s, the case was revisited when historical research documented that the government had hidden or knowingly falsified evidence during the original trials. Through the use of a petition for a writ of error coram nobis , Yasui's conviction was eventually vacated.

For More Information

Minoru Yasui v. U.S., 320 U.S. 115 (1943), http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?court=us&vol=320&invol=115 .

Bangarth, Stephanie. Voices Raised in Protest: Defending Citizens of Japanese Ancestry in North America, 1942–49 . Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008.

Irons, Peter. Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases . New York: Oxford University Press, 1983. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Kessler, Lauren. Stubborn Twig: Three Generations in the Life of a Japanese American Family . New York: Random House, 1993.

Yamamoto, Eric, Margaret Chon, Carol L. Izumi, Jerry Kang, and Frank H. Wu. Race, Rights, and Reparation: Law and the Japanese American Internment . Gaithersburg, Md.: Aspen Law & Business, 2001.

Last updated Oct. 5, 2020, 6:05 p.m..

Media

Media