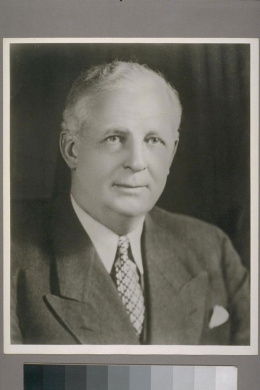

Culbert Olson

| Name | Culbert Olson |

|---|---|

| Born | 1876 |

| Died | April 13 1962 |

| Birth Location | UT |

Culbert Olson (1876–1962) successfully campaigned in 1938 for the governorship of California on a New Deal platform, enjoying the open support of President Roosevelt. It came as no surprise, then, that Olson would become a staunch advocate of Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066 . But the one-term governor who allowed thousands of his state's residents to be expelled from their homes would be defeated in 1942 by Earl Warren , an even more zealous proponent of the removal and imprisonment of Japanese Americans.

Culbert Olson, born in 1876, was a lawyer in his native state of Utah, earning a reputation as a political progressive and a defender of labor unions. He moved to California in 1920 and was elected to the state senate in 1934 as a Democrat representing Los Angeles. When he ran for the state's highest office four years later, no Democrat had served as governor of California for forty years.

Olson held a number of left-leaning positions, opposing oil company monopolies, backing compulsory universal health insurance, and promoting reform of the state penal system. Despite a long career as an activist for the rights of the common man, Olson joined liberals and conservatives alike in anti-Japanese fervor.

Soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor, California's Attorney General Earl Warren began investigating Japanese land holdings, looking for violations of the state's Alien Land Law , while Olson attempted to revoke the professional and business licenses of " ." In January of 1942, General John DeWitt held a series of meetings to discuss options for "mass evacuation" of West Coast residents of Japanese ancestry. Olson recommended moving California's Issei inland, a position DeWitt briefly embraced before Provost Marshal General Allen Gullion and, especially, his assistant Karl Bendetsen pressed DeWitt to endorse harsher measures that would apply to both aliens and American citizens. [1]

Still, Olson was in agreement with Warren and DeWitt, upon whose recommendations E.O. 9066 rested, about the potential for sabotage coming from the California's ethnic Japanese population. Olson, reacting to information from DeWitt, believed that evidence existed supporting Japanese residents of California preparing for fifth column activities. They argued that an act of sabotage must be imminent because none had yet occurred, completely dismissing the possibility that DeWitt's information was false and that no incident would be forthcoming.

Shortly after the issuance of E.O. 9066 on February 19, 1942, Olson testified before a U.S. Congressional committee charged with studying potential problems resulting from the order. On March 6, 1942, Governor Olson stated that, "because of the extreme difficulty in distinguishing between loyal Japanese Americans, and there are many who are loyal to this country, and those other Japanese whose loyalty is to the Mikado. I believe in the wholesale evacuation of the Japanese people from coastal California." [2]

The expulsion of all Japanese immigrants and their descendants from California would, however, have a serious impact on agricultural output. Olson believed the exclusion zone, as he had testified before the Congressional committee, should be limited to "coastal California." Instead, he proposed that adult Japanese men should live inland, in work camps, so they could harvest crops in the state's productive Central Valley. It is possible that Olson considered the potential for a different race problem caused by the removal of Japanese communities and subsequent influx of job seekers. Author Michi Weglyn charged that Olson feared "inundation of the state by Blacks and Chicanos would be unavoidable." [3]

Yet Olson promoted the image of a racially tolerant atmosphere in his state. Olson said, "Californians have kept their heads...There have been few if any serious denials of civil rights to either aliens or citizens of Japanese race, on account of the war. The American tradition of fair play has been observed...all the organs of public influence and information—press, pulpit, school welfare agencies, radio and cinema—have discouraged mob violence and have pleaded for tolerance and justice for all law abiding residents of whatever race." [4] By the time 93,000 California residents of Japanese heritage were expelled from their homes and imprisoned in desolate and remote "camps," Olson's statements rang especially hollow.

The Republican Party nominated Earl Warren to run against Culbert Olson and Warren soundly defeated him. Olson returned to his law practice and, as an atheist, lead the United Secularists of America. Olson's wife had died shortly after his inauguration as governor. He died on April 13, 1962 at the age of 85.

For More Information

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997.

Daniels, Roger. Concentration Camps North America: Japanese in the United States and Canada During World War II . Malabar: Krieger Publishing Company, 1993.

Hosokawa, Bill. Nisei: The Quiet Americans . Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2002.

Schlenker, Gerald. "The Internment of the Japanese of San Diego County During the Second World War." In The Journal of San Diego History, San Diego Historical Society Quarterly . Edited by James E. Moss. Winter 1972, Vol. 18, No. 1. https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1972/january/internment/#:~:text=Early%20in%20March%20the%20Board,one%20could%20not%20distinguish%20a

Smith, Page. Democracy on Trial . New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

Weglyn, Michi Nishiura. Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America's Concentration Camps . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996.

Footnotes

- ↑ Page Smith, Democracy on Trial (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 112-113.

- ↑ "Olson Wants All Japs Moved: Tells Committee Some Might Be Returned," United Press, San Francisco News , March 6, 1942.

- ↑ Michi Nishiura Weglyn, Years of Infamy (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996), 94.

- ↑ Smith, Democracy on Trial , 100.

Last updated Feb. 15, 2024, 10:43 p.m..

Media

Media