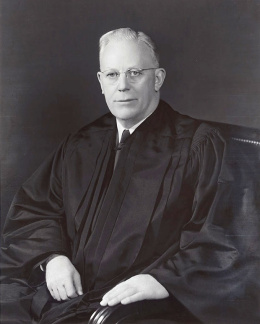

Earl Warren

| Name | Earl Warren |

|---|---|

| Born | March 19 1891 |

| Died | July 1 1974 |

| Birth Location | Los Angeles, CA |

Governor of California and chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. One of the most influential Supreme Court justices in the country's history, the Warren Court over which he presided was renowned for its expansion of civil liberties in the mid-20th century. However, in 1942, as the attorney general of the state of California, Warren was a vocal proponent of forcibly removing all Japanese Americans from the West Coast. He would express regret for his wartime actions in his posthumously published memoirs.

Before the War

Earl Warren (1891–1974) was born on March 19, 1891, in Los Angeles, California, to Erik Methais "Matt" Warren and Christine "Crystal" Hernlund. Both of his parents had come to America with their families as young children, his father from Norway, his mother from Sweden. His father lost his job when Earl was three and the family moved to Sumner, a town just outside of Bakersfield, California, located in the desert east of Los Angeles. His father found work repairing railroad cars and eventually made a living in real estate. Earl grew up in Sumner and moved to Berkeley in 1908 to attend the University of California, earning an undergraduate degree and continuing on to law school at Boalt Hall, earning his law degree in 1914. While in school, he worked on the gubernatorial campaign of Hiram Johnson , a progressive Republican.

Upon graduation, he practiced law, but found it unsatisfying. When the U.S. entered World War I, he volunteered, and rose from private to first lieutenant, exiting in December 1918. In 1920, he was hired as a deputy district attorney by Alameda County and, when a vacancy for the top job came in 1925, he was appointed to fill it. He won reelection in 1930 and 1934, gaining a national reputation for effectiveness and incorruptibility. He also started to become active in Republican Party politics by the late 1920s and was elected chairman of the State Republican Central Committee in 1934. He ran for state attorney general in 1938 and won by an overwhelming margin.

Proponent of Exclusion

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor , Warren emerged as one of the leading western political figures advocating the mass removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast states. As attorney general, Warren had demonstrated a preoccupation with preparedness and with civil defense; as a native Californian, he could not help but have absorbed some of the state's anti-Japanese attitudes, though he never showed such sentiments outwardly. He was a member of the American Legion and Native Sons of the Golden West , organizations that had often expressed anti-Japanese sentiments.

As was the case with other exclusion proponents, his advocacy became more extreme between December 1941 and February 1942. One of his first acts actually came in support of Japanese Americans, when he fought the California State Personnel Board's attempt to prevent Japanese Americans from taking the civil service exam and suspending all Japanese American civil service employees. But over time—and through frequent meetings with General John DeWitt , the military leader charged with the security of the West Coast—he moved towards a position advocating mass removal of all Japanese Americans, including American citizens.

His argument for mass eviction had three main components. He had convened a meeting of state law enforcement officials and asked them to map local Japanese American land holdings in their areas. The resulting maps showed concentrations of Japanese American owned lands near sensitive areas such as power lines, railroads, military bases, and oil fields leading Warren to conclude "Such a distribution of the Japanese population appears to manifest something more than coincidence"; indeed, "the Japanese population of California is, as a whole, ideally suited… to carry into execution a tremendous program of sabotage on a mass scale should any considerable number of them be inclined to do so." [1] The fact that coastal land was well suited for farming and the scraps of land along railroads and power lines were relatively undesirable—and thus available to Japanese—didn't seem to occur to him. His presentation of these maps before the Tolan Committee was so convincing that DeWitt lifted much of it for his Final Report, Japanese Evacuation From the West Coast, 1942 .

A second component was the idea that there was no way to determine the "loyalty" of Japanese Americans, and that there was some racial predisposition to supporting Japan, a belief shared by many people at that time. While it was possible to determine the loyalty of German or Italian Americans, "when we deal with the Japanese we are in an entirely different field and we cannot form any opinion that we believe to be sound." [2]

The third and related component was what historian Roger Daniels sarcastically dubbed the "Invisible Deadline for Sabotage" theory: the idea that the complete lack of espionage or sabotage activity by Japanese Americans was not an indication there wasn't going to be any, but rather a sign that some massive coordinated activity was coming at an unknown future date. [3]

Warren's actual influence on the exclusion policy is debatable. As a California state official, he had no direct impact in formulating that policy. However, he no doubt influenced officials like General DeWitt who did help to form policy as well as newspaper columnist Walter Lippmann , whose influential column advocating mass removal espoused the "invisible deadline" theory.

Elected governor of California in November 1942, Warren—like most West Coast politicians—continued to oppose the return of Japanese Americans to his state. He told the Dies Committee in 1943 that "we don't propose to have the Japs back in California during this war if there is lawful means of preventing it." [4] But when Japanese Americans were allowed back to the West Coast in January of 1945, he urged Californians to respect their rights in the name of the war effort.

Postwar Governor of California and Supreme Court Justice

Warren enjoyed great popularity as governor of California and won reelection by large margins in 1946 and 1950 in a state with a Democratic majority. Given his popularity along with his ideal family—he had been married since 1925 to Nina Palmquist Myers and had six children—national political office came calling in the form of being the vice-presidential running mate of Thomas Dewey in 1948. Though the ticket lost, he gained greater national exposure and was briefly a candidate for president in 1952 before supporting Dwight D. Eisenhower's campaign. Upon Eisenhower's election, the new president promised Warren the first vacancy on the Supreme Court. However when Chief Justice Fred Vinson died in 1953, Eisenhower hesitated to name Warren chief justice, considering, among others, Japanese American exclusion architect John McCloy for the post. However, after heavy behind the scenes lobbying, Eisenhower eventually did name Warren to the post in late September 1953.

One of his first decisions was his most momentous: in May 1954, the Court delivered a unanimous verdict authored by Warren in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka , which ruled racial segregation in the public schools unconstitutional. Split prior to Warren's appointment, he used his political and persuasive skills to unify all nine justices behind the verdict, which was seen as particularly important in such a politically sensitive case. Over the next decade and a half, the Warren Court greatly expanded civil rights and civil liberties and the rights of the accused.

After the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, President Lyndon Johnson asked Warren to head an official investigation. Reluctant to do it, the President appealed to Warren's patriotism and the potential danger of all the rumors and conspiracy theories circulating. Warren agreed. However, the Warren Commission's report—which concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald had acted alone—was greeted with great skepticism by the public and did little to quell conspiracy theorists.

Warren retired from the Supreme Court in 1969. Despite his stated intent to appoint someone who would reverse much of the work of the Warren Court, President Richard Nixon's choice, Warren Burger ended up actually expanding some of what Warren had started.

Legacy

As his legacy as a civil libertarian grew, the seeming anomaly of his wartime support of Japanese American exclusion remained a black mark on his record. Yet despite having had many opportunities to admit error, he never did so publicly. As chief justice in 1962, he defended the court's decisions in the Hirabayashi , Yasui , and Korematsu cases, arguing that "there are some circumstances which the Court will, in effect, conclude that it is simply not in a position to reject descriptions by the Executive of the degree of military necessity." [5] Japanese American activist Edison Uno was among those who fruitlessly wrote Warren seeking an apology starting in the late 1960s. At a presentation at Boalt Hall in 1969 titled "Observations on Human Rights and Racial Discrimination," he faced a group of Japanese American students. Afterwards, one asked him "Is it true that you, of all principal figures involved, are the only one who has refused to admit error?" to which he replied, "Yes, that is true. I never apologize for a past act. Besides, that is just a matter of history now." [6]

At the urging of his son, he agreed to lend his support to late 1960s efforts to repeal Title II of the Internal Security Act . In a letter to Japanese American Citizens League president Jerry Enomoto, he wrote "I express these views as the experience of one who as a state officer became involved in the harsh removal of the Japanese from the Pacific Coast in World War II, almost 30 years ago." [7] In a 1972 oral history interview, he stated, "I feel that everybody who had anything to do with the relocation of the Japanese, after it was all over, had something of a guilty consciousness about it, and wanted to show that it wasn't a racial thing as much as it was a defense matter." According to Edward G. White a former Warren clerk, tears rolled down his face when he mentioned the faces of children separated from their parents and the interview was temporarily stopped. [8] In June 1974, he told former inmate Morse Saito that he felt the "greatest regret" for his support of mass eviction. [9]

His posthumously published memoirs finally fully acknowledged his error, repeating some of the language from the 1972 interview:

I have since deeply regretted the removal order and my own testimony advocating it, because it was not in keeping with our American concept of freedom and the rights of citizens. Whenever I thought of the innocent little children who were torn from home, school friends, and congenial surroundings, I was conscience-stricken. It was wrong to react to impulsively, without positive evidence of disloyalty, even though we felt we had a good motive in the security of our state. [10]

Warren suffered his third heart attack in July 1974 and died a week later in Washington, D.C. at the age of 83.

For More Information

Newton, Jim. Justice for All: Earl Warren and the Nation He Made . New York: Riverhead Books, 2006.

Warren, Earl. The Memoirs of Earl Warren . New York: Doubleday & Company, 1977.

White, G. Edward. Earl Warren: A Public Life . New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

__________. "The Unacknowledged Lesson: Earl Warren and the Japanese Relocation Controversy" Virginia Quarterly Review (Autumn 1979): 613–29. http://www.vqronline.org/articles/1979/autumn/white-unacknowledged-lesson/ .

New York Times obituary by Alden Whitman: https://www.nytimes.com/1990/09/05/nyregion/obituary-alden-whitman-is-dead-at-76-made-an-art-of-times-obituaries.html

Record of the Earl Warren Papers at the California State Archives. http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf4b69n6gc/ .

A Register of His Papers in the Library of Congress. http://international.loc.gov/service/mss/eadxmlmss/eadpdfmss/2000/ms000012.pdf .

Footnotes

- ↑ Jim Newton, Justice for All: Earl Warren and the Nation He Made (New York: Riverhead Books, 2006), 131.

- ↑ Newton, Justice for All , 136.

- ↑ Roger Daniels, Concentration Camps, North America: Japanese in the United States and Canada during World War II (Malabar, Fla.: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Co., 1981), 76.

- ↑ Greg Robinson, By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), 193.

- ↑ G. Edward White, "The Unacknowledged Lesson: Earl Warren and the Japanese Relocation Controversy" Virginia Quarterly Review (Autumn 1979).

- ↑ Newton, Justice for All, 139.

- ↑ Newton, Justice for All , 140.

- ↑ G. Edward White, Earl Warren: A Public Life (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), 76–77.

- ↑ Alice Yang Murray, Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008), 189.

- ↑ Earl Warren, The Memoirs of Earl Warren (New York: Doubleday & Company, 1977), 149.

Last updated Dec. 15, 2023, 5:28 p.m..

Media

Media