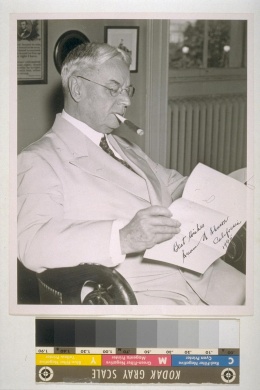

Hiram Johnson

| Name | Hiram Warren Johnson |

|---|---|

| Born | September 2 1866 |

| Died | August 6 1945 |

| Birth Location | Sacramento, CA |

The governor of California from 1911 to 1917 and a five-term United States senator from California, Hiram Johnson (1866–1945) signed the 1913 alien land act into law and as a senator, played a key role in the passage of Japanese exclusion in 1924. One of the leading exponents of isolationism and unilateralism between the wars, Johnson's was one among many voices from the West calling for the mass removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast.

Before the War

Hiram Warren Johnson was born on September 2, 1866, to Grove and Ann Johnson in Sacramento, California, the fourth of five children. His father was a successful lawyer and politician, who served in the state assembly and senate and served one term in the U.S. House of Representatives. He entered the University of California in Berkeley in 1884, but left in his junior year to marry Minnie McNeal, taking a job in his father's law office as a stenographer. In 1888, he passed the bar and became a law partner with his father and brother Albert. He and Albert managed his father's successful run for the Congress in 1894, but the brothers later broke with their father over a Sacramento mayoral election and moved their law practice to San Francisco.

In San Francisco, Johnson became part of a special prosecution team that saw the conviction of elected officials and political bosses, and he rode his subsequent popularity and notoriety to the governor's office in 1910. In 1912, he broke off with the Republicans and ran for vice-president as Theodore Roosevelt's running mate in 1912.

California's anti-Japanese movement reigned during his time as governor, and, despite his initial opposition, he signed the 1913 alien land act into law, rejecting entreaties from the Woodrow Wilson administration. He rationalized that the measure was not discriminatory, since it was the federal government that prohibited citizenship to certain races. Given the overwhelming support of the measure—the Senate voted 35 to 2 in favor and the House 72 to 3—he told Wilson's envoy William Jennings Bryan, "With such unanimity of opinion, even did I hold other views, I would feel it my plain duty to sign the bill, unless some absolutely compelling necessity demanded contrary action. Apparently no such controlling necessity exists." [1]

Reelected governor in 1914, Johnson successfully ran for the United States Senate in 1916, resigning the governorship. His long senate tenure was marked by his influence on foreign relations and advocacy of unilateralism and non-intervention. His biographers Michael A. Weatherson and Hal Bochin write that he "was the primary spokesman for neutrality during the period between World War I and World War II." [2] He opposed the League of Nations treaty and helped prevent America's participation in the World Court. And as one of the leaders of a coalition of Western state congressional members, he also played a key role in the prohibition of Japanese immigration that was part of the Immigration Act of 1924 , working closely with friend and anti-Japanese leader V.S. McClatchy .

World War II

As the senior member of the West Coast congressional delegation, Johnson played a role in creating the public outcry that made mass removal and incarceration possible. At the urging of Senator Rufus C. Homan of Oregon and as nominal leader of the West Coast congressional delegation, Johnson called a general meeting of congressmen and senators from the three states in his office on February 2, 1942, to discuss defense measures in their states and the dangers of fifth column activity. Out of that meeting, two committees were formed, one of which, the Committee on Alien Nationality and Sabotage headed by Senator Monrad C. Wallgren of Washington, would go on to agitate for the exclusion of Japanese Americans. Later, on March 24 and 25, 1942, Johnson held subcommittee hearings with Senators Tom Stewart of Tennessee and Burnet Maybank of South Carolina, on Stewart's bill that that would authorize "the secretary of war to detain all enemy aliens and any native-born citizen believed to have ties with the enemy." [3] Undoubtedly due to his failing health, Johnson was not otherwise active with regard to the Japanese American question, and his role in the Senate diminished. He was too weak to walk two blocks to his office by 1942 and a 1943 stroke paralyzed him for several weeks. He died while still in office on August 6, 1945.

His papers are at the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. Hiram Johnson High School in Sacramento is named after him.

For More Information

California Museum. "California Hall of Fame: Hiram Johnson." http://www.californiamuseum.org/exhibits/halloffame/inductee/hiram-johnson .

Daniels, Roger. The Politics of Prejudice: The Anti-Japanese Movement in California and the Struggle for Japanese Exclusion . 1962. 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977.

Grodzins, Morton. Americans Betrayed: Politics and the Japanese Evacuation . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1949.

Hiram Johnson Papers. Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley. http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf8t1nb3kr/ .

Robinson, Greg. A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in North America . New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

Weatherson, Michael A., and Hal Bochin. Hiram Johnson: A Bio-Bibliography . New York: Greenwood Press, 1988.

Last updated June 12, 2020, 4:46 p.m..

Media

Media