Tolan Committee

The House Select Committee Investigating National Defense Migration, commonly known as the "Tolan Committee," held hearings in February and March 1942 in four cities about the possible removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. The hearings began two days after Pres. Franklin Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066 authorized the exclusion from the Pacific Coast of any and all persons that the U.S. military deemed a threat. The Committee did not issue its final report until May 1942, so it played no official role in the decision to remove or incarcerate Japanese Americans. Nevertheless, as hundreds of people presented testimony or written statements to the Committee, it became a major conduit for those trying to influence government policy on this issue. Most historians agree that the Tolan Committee's failure to recommend that U.S. citizens and non-citizens of Japanese descent be accorded the same rights as their counterparts of German and Italian descent represented the final capitulation of the U.S. government to the racist policy of mass removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans.

Organization and Purpose

Representative John Tolan, a Democrat from Oakland, California, was a New Deal liberal who had entered Congress in 1935, and he headed the committee that began in 1940 as the Select Committee to Investigate the Interstate Migration of Destitute Citizens. Thus, the Committee's initial hearings centered on the problems that refugees from the Dust Bowl encountered as they moved west. By 1941, as workers flocked to military production jobs with the nation preparing for war, the Committee changed its focus and its name to the House Select Committee Investigating National Defense Migration. The other members of the Tolan Committee were John Sparkman (D-Alabama), Laurence Arnold (D-Illinois), Carl Curtis (R-Nebraska), and George Bender (R-Ohio). Sparkman was also a New Dealer, albeit a virulent opponent of civil rights for African Americans. Curtis and Bender, both elected to the House in 1938, believed President Roosevelt and the New Deal to be far too liberal.

As discussion increased in early 1942 about the removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast, some liberals, including Carey McWilliams , believed that a sympathetic Committee chairperson such as Tolan could help forestall the most extreme anti-Nikkei actions. The Committee held hearings in San Francisco on February 21, 23, and March 12, in Portland on February 26, in Seattle on February 28 and March 2, and in Los Angeles on March 6 and 7. During the early sessions much of the testimony centered on whether any group of people should be removed from their homes en masse. In the later sessions, as the policy of removal became a fait accompli, some testimony shifted to the logistics of removal, and how to make it more humane. In all four cities, but especially in San Francisco and Los Angeles, the Committee took testimony not only regarding Japanese Americans but also regarding German and Italian nationals on the West Coast. For example, the Nobel Prize-winning author Thomas Mann, a refugee from Nazism, spoke about German expatriates in California, but made no reference to proposals to remove Japanese Americans from the West Coast. [1]

Testimony for and Against Mass Removal

Most of those who gave oral testimony on Japanese Americans to the Tolan Committee supported removal, though a significant minority opposed singling out Japanese Americans on a racial basis for removal from the West Coast. Forty-five of the non-Japanese American witnesses who gave testimony at the hearings favored removal or exhibited strong anti-Japanese American sentiments. Thirty-four of the non-Japanese American witnesses spoke clearly against the mass removal of Japanese Americans, and twelve others at least expressed concern for the rights of Japanese Americans. (These figures do not include those who spoke only about German or Japanese nationals, or who, like several FBI agents, spoke only on technical or logistical questions.) Of the written statements submitted, a greater percentage favored removal. Of the nineteen Japanese Americans who testified in person, eleven spoke clearly against removal. However, even most of those–whether whites or Japanese Americans–who testified that removal was bad policy or violated constitutional rights stated that they would cooperate with removal if it were implemented, so as not to harm the war effort. [2]

Elected political leaders, American Legion representatives, and business owners were most likely to call for removal and to question whether anyone of Japanese descent, whether a U.S. citizen or not, could be a loyal American. For example, Angelo Rossi, the mayor of San Francisco, strictly counterposed German and Italian aliens resident in the U.S. as loyal while he called for the removal of all Issei and most Nisei . [3] Los Angeles mayor Fletcher Bowron similarly supported the removal of "the entire Japanese population" because he knew of "no way to separate those who say they are patriotic and are, in fact, loyal at heart, and those who say they are patriotic and, in fact, are loyal to Japan." [4] Other politicians who spoke in favor of mass removal included California Attorney General Earl Warren —who would later, as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, be much more solicitous of civil rights—and Seattle mayor William Millikin. [5] Fred Fueker of the American Legion was one of several representatives of the veterans' group who called for the removal of all people of Japanese descent from the West Coast along with other "enemy aliens," and he presented the Committee with dozens of resolutions from affiliates of his powerful organization. [6]

The mayors of Berkeley, California, and Tacoma, Washington, were the only two elected officials who expressed support at the hearings for rights for Japanese Americans. [7] But supporters of Japanese American rights included almost all of those associated with universities and social welfare organizations, along with a sprinkling of business owners and farmers. As the Committee noted in its final report, "Every spokesman for religious organizations who testified on the west coast advocated individual treatment of the Japanese," not wholesale removal. [8] Two statements may be taken as representative of the arguments against mass removal. Jesse Steiner, chair of the University of Washington Sociology Department, stated that government acceptance of mass removal, in contrast to selective evacuation based on individual charges, amounted to race prejudice, and he compared it to "the treatment of minorities by the totalitarian governments in Europe and Asia." [9] Esther Boyd, a hardware store owner in Washington's Yakima Valley, praised the industriousness, honesty, and personal loyalty of Japanese Americans in her agricultural region, and attributed demands for removal to spite and economic greed by white farmers. [10]

Some who opposed the scapegoating of Japanese Americans nevertheless presented ambiguous or timid statements at the Committee hearings. A representative of the Puget Sound chapter of the American Association of Social Workers asserted the need to protect citizens' constitutional rights and denounced racially-based mass removal, but nevertheless expressed confidence in the government's handling of the issue and offered to help in the planning necessary to make any partial evacuation humane. [11] Even Carey McWilliams, later an outspoken critic of removal and incarceration, stated that removal, if conducted properly, would reassure Japanese Americans of their inclusion in American democracy. [12]

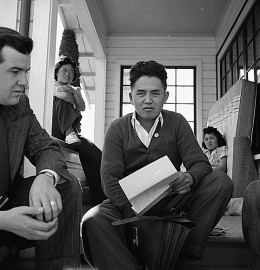

Among Japanese Americans who testified, journalist James Omura strongly denounced the proposed mass removal of Nisei, comparing it to Hitler's prewar mistreatment of Jews. [13] Japanese American Citizens League leader Mike Masaoka , however, tried to balance criticism of the policy with support for the government in wartime:

If in the judgment of military and Federal authorities, evacuation of Japanese residents

from the West Coast is a primary step toward assuring the safety of this nation, we will have no hesitation in complying...But if, on the other hand, such an evacuation ...cloaks the desires of political or pressure groups who want us to leave merely

from motives of self-interest, we feel we have every right to protest... [14]

Recommendations

The Committee's final report, released on May 13, included an objective summary of the testimony; a review of the history of Japanese immigration, legal status, social structure, and economic position on the West Coast; and comments on German and Italian aliens. Among its main recommendations were that the U.S. government needed to take stronger steps to safeguard the property of those removed from the West Coast. The Tolan Committee's efforts contributed to the Roosevelt Administration's designation of the Federal Reserve Bank as the agency which would help Japanese Americans deal with homes, mortgages, and finances, and the Farm Security Administration as the agency to ensure that Japanese American farms remained productive and that ownership not be compromised while their owners were incarcerated. These recommendations undoubtedly prevented some economic losses by Japanese Americans, although such losses were still tragically high. [15]

The Tolan Committee did endorse the plan to remove all Japanese Americans, whether U.S. citizens or not, from the West Coast, and concluded that, due to the state of public opinion, neither Issei nor Nisei could live or work freely even east of the restricted areas. The Committee framed its support for such injustices around the need for the War Relocation Authority to provide ways for incarcerated Japanese Americans to make a living, to contribute to the war effort, and to prepare for postwar life in the nation. Perhaps the most disappointing aspect of the Tolan Committee was its refusal to call for individual hearing boards to determine the loyalty of any Japanese Americans, whether U.S. citizens or not, even as it recommended such hearing boards for German and Italian aliens living on the West Coast to avoid the mass detention or removal of these groups. With its conclusions couched in the language of the New Deal, the Tolan Committee represents the abdication of responsibility by mainstream liberalism during World War II for the mistreatment of Japanese Americans.

For More Information

"Interrupted Lives: Japanese American Students at the University of Washington, 1941-1942," at https://www.lib.washington.edu/specialcollections/collections/exhibits/harmony/interrupted , accessed 2 July 2012.

Robinson, Greg. A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in North America . New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

Saccento, Matthew. "The Tolan Committee and the Internment of Japanese Americans." B.A. Thesis, Wilkes Honors College, Florida Atlantic University, 2008, at http://www.scribd.com/doc/86674058/Tolan-Committee-and-the-Internment-of-Japanese-Americans , accessed 2 July 2012.

Shaffer, Robert. "Cracks in the Consensus: Defending the Rights of Japanese Americans During World War II." Radical History Review #72 (Fall 1998): 84-120.

Smith, Page. Democracy on Trial: The Japanese American Evacuation and Relocation in World War II . New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

United States. Congress. House. Select Committee Investigating National Defense Migration, 77th Cong., 2nd sess. National Defense Migration. Parts 29, 30, 31: Problems of Evacuation of Enemy Aliens and Others from Prohibited Military Zones (Tolan Committee hearings), at www.bpl.org/online/govdocs/interstate_migration.htm (click on Parts 29, 30, 31)

United States. Congress. House. Select Committee Investigating National Defense Migration.77th Cong., 2nd sess. National defense migration, Fourth interim report ...Findings and recommendations on evacuation of enemy aliens and others from prohibited military zones (Tolan Committee report). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1942.

Footnotes

- ↑ United States. Congress. House. Select Committee Investigating National Defense Migration. 77th Congress, 2nd sess. National Defense Migration (hereafter Tolan Committee hearings), Part 31, 11725-11733.

- ↑ For more complete analysis of the Tolan Committee hearings, see Robert Shaffer, "Cracks in the Consensus: Defending the Rights of Japanese Americans During World War II," Radical History Review #72 (Fall 1998): 84-120, and Matthew Saccento, "The Tolan Committee and the Internment of Japanese Americans" (B.A. Thesis, Wilkes Honors College, Florida Atlantic University, 2008).

- ↑ Quoted in Greg Robinson, A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in North America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 107.

- ↑ Tolan Committee hearings, Part 31, 11644.

- ↑ Tolan Committee hearings, Part 29, 10973ff and Part 30, 11404ff.

- ↑ Tolan Committee hearings, Part 30, 11433ff.

- ↑ Tolan Committee hearings, Part 29, 11095ff and Part 30, 11410ff.

- ↑ United States. Congress. House. Select Committee Investigating National Defense Migration. 77th Congress, 2nd sess. National Defense Migration, Fourth Interim Report , 148.

- ↑ Tolan Committee hearings, Part 30, 11558.

- ↑ Tolan Committee hearings, Part 30, 11582ff.

- ↑ Tolan Committee hearings, Part 30, 11541-11552.

- ↑ Tolan Committee hearings, Part 31, 11788ff.

- ↑ Tolan Committee hearings, Part 29, 11231.

- ↑ Tolan Committee hearings, Part 29, 11137.

- ↑ For this interpretation of the Tolan Committee's impact, see esp. Page Smith, Democracy on Trial: The Japanese American Evacuation and Relocation in World War II (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), chap. 9.

Last updated Dec. 21, 2023, 3:10 a.m..

Media

Media