Mike Masaoka

| Name | Mike Masaoka |

|---|---|

| Born | October 15 1915 |

| Died | June 26 1991 |

| Birth Location | Fresno, CA |

| Generational Identifier |

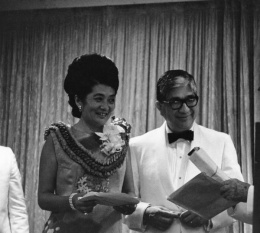

Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) leader and lobbyist. One of the witnesses to testify before the Tolan Committee in the wake of Executive Order 9066 and original member of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team , Mike Masaru Masaoka (1915-1991) was an influential but controversial figure in the history of the Japanese American incarceration. As JACL representative at the congressional hearings, he opposed the mass removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast, but vowed to comply if such measures fell under military necessity . He also chose to serve the country in uniform while many citizens of Japanese descent were still confined to prison camps. His assimilationist strategy as JACL leader has left a legacy of debate about the meaning of wartime loyalty and patriotism.

Before the War

Mike Masaoka was born in Fresno, California, in 1915 as the fourth child of Japanese immigrants from Hiroshima and Kumamoto prefectures. His family moved to Salt Lake City where his father operated a small fish market. When Masaoka was nine years old, his father was killed in an automobile accident, leaving his mother to raise eight children on her own. Upon graduating from the University of Utah, he accepted an instructorship in the department of speech until he moved to San Francisco to work for the JACL. He was named executive secretary in August 1941.

Critical to Masaoka’s rise as a spokesperson for the JACL was Utah's political science professor turned Senator, Elbert D. Thomas, a Mormon missionary who had lived in Japan as a youth. As a member of the Senate Education and Labor Committee, Senator Thomas invited Masaoka to a hearing held by the Presidential Commission on Equal Employment Opportunities in Los Angeles. Masaoka has also recalled that Senator Thomas may have had a hand in Curtis B. Munson’s visit to the JACL office while investigating Japanese American loyalty. (See Munson Report .) Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Masaoka was jailed in North Platte, Nebraska, where he was recruiting for the JACL. Senator Thomas arranged for Masaoka's release. [1] Masaoka's political ties with Washington would become more prominent and pronounced as the crisis progressed.

Wartime Role and Debate

As Japanese-language newspapers were forced to shut down in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, Masaoka attempted to keep the line of communication alive by producing news bulletins and distributing them to JACL chapters. This, in effect, placed the JACL in the position of censoring and disseminating news stories intended to offset government suspicion. He next turned his attention to public relations work. In his autobiography, Masaoka writes that the "JACL urged its members to cooperate with authorities, buy war bonds, volunteer for civil defense units, sign up for first-aid classes and donate blood, look for good newspaper publicity, and, in short, do everything to project a favorable patriotic image." [2] That New Year's Eve, he addressed fellow JACL members with a message proclaiming his allegiance to the United States, consistent with his manifesto, the " Japanese-American Creed ," penned in 1940 for the JACL national convention.

Masaoka's pro-American ideology would shape the JACL's course of action and, in turn, affect government policy on Japanese Americans throughout the Second World War. As the war broke out between the U.S. and Japan, key Issei leaders were immediately arrested and incarcerated. Amid the power vacuum created by the disintegration of Issei leadership, Masaoka found himself as the liaison between the War Relocation Authority (WRA) and the Japanese American community as plans for forced migration became closer to reality. In a show of ultimate loyalty to the country, Masaoka approached the army with a proposal to form a suicide battalion of Nisei volunteers. Lest any doubt remain, they would offer their parents as hostages. The army responded instead with an advisory role for Masaoka on how to operate the prison camps and later appointed him head of the Japanese American Advisory Council. [3] Meanwhile, his testimony at the Tolan Committee already underway proved ineffective in saving the Nisei from mass incarceration, which many believe was a foregone conclusion. When the 442nd Regimental Combat Team was formed, Masaoka became the first to volunteer and urged other Nisei to enlist as proof of their loyalty. He has defended his controversial position on the internment in his autobiography arguing that cooperation was essential if some safeguards were to be provided by the government.

Masaoka's loyalty campaigns were not without critics and his wartime actions remain a contested issue. His emphasis on patriotic duty went so far as reporting to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) on what the JACL considered traitorous elements within the Japanese American community. He opposed challenging the evacuation order in court on the grounds that any violation of the law was a subversive act that "would hurt the majority." [4] His ideas for resettlement to unrestricted zones were also predicated on the demonstration of loyalty. Despite making administrative recommendations for the WRA camps, he was never an inmate. The army had made an exception for him to head directly to Washington without going through the detention process.

After the War

Masaoka became a lobbyist in the postwar years on behalf of Japanese Americans in bringing changes to U.S. immigration and naturalization policies. He was behind the passage of the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act of 1948, which attempted to compensate Japanese Americans for material losses incurred as a result of their mass detainment. He also played a role in mending U.S–Japanese relations, resulting in an invitation to the signing of the San Francisco Peace Treaty in 1951 that brought the Allied occupation of Japan to a close the following year. His lobbying efforts have been credited for the success of the McCarran-Walter Immigration and Naturalization Act that allowed the Issei to become eligible for citizenship for the first time in 1952. Though not a cure-all, it virtually repealed the Japanese exclusion clause of the Immigration Act of 1924 that had barred Japanese immigration. In his later years, he began his own consulting business for Japanese and American agricultural and commercial interests. He initially opposed individual monetary redress for camp survivors, but later supported the reparations. He resided in the Washington area until his death on June 29, 1991.

Posthumous Controversy

In 2000, Masaoka became the focus of a public debate regarding a national memorial in Washington D.C. commemorating the Japanese American incarceration and Nisei who served in the military during World War II. At issue was the memorial's inscription of Masaoka's name and quote from the "Japanese-American Creed" honoring his wartime role as "civil rights advocate," when no such consensus exists in the Japanese American community. Critics argued that the inclusion of Masaoka in the National Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism would send an erroneous message that identifies patriotism with government cooperation. They also questioned the glaring omission of other "heroes" who resisted imprisonment and the draft. Supporters of the memorial included historian Bill Hosokawa who described Masaoka as "cocky, aggressive, bursting with enthusiasm and ideas" as JACL leader. "I know the vigor and intensity with which we opposed the evacuation," he said, "So I think the opposition to Mike is unfair." Opponents instead highlighted "his arrogance, his ego, his mistakes." [5] Yet, in a surprising turn of events, the JACL made a formal apology to the resisters for failing to recognize their loyalty. Although voting to support the memorial, the recognition marked the first step towards reconciliation and healing from the painful legacy of division.

For More Information

Committee for a Fair and Accurate Japanese American Memorial. http://www.javoice.com/pamphlet1.html#Anchor-AN-33869

Hosokawa, Bill. Nisei: The Quiet Americans . Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 2002.

Masaoka, Mike. Conscience and Constitution audio interview about wartime actions of the JACL. DVD directed by Frank Abe. http://www.resisters.com/jacl/index.htm

Masaoka, Mike with Bill Hosokawa. They Call Me Moses Masaoka: An American Saga . New York: William Morrow, 1987.

Spickard, Paul. "The Nisei Assume Power: The Japanese-American Citizen's League, 1941–1942." Pacific Historical Review 52:2 (May 1983): 147-174.

Takahashi, Jere. Nisei/Sansei: Shifting Japanese American Identities and Politics . Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1997.

Footnotes

- ↑ Bill Hosokawa, Nisei: The Quiet Americans (Boulder: The University of Colorado Press, 2002), 205, 213, 228.

- ↑ Mike Masaoka, They Call Me Moses Masaoka: An American Saga (New York: William Morrow, 1987), 76.

- ↑ Paul Spickard, "The Nisei Assume Power: The Japanese American Citizen's League, 1941–1942, Pacific Historical Review 52:2 (May, 1983): 164-165.

- ↑ Masaoka, They Call Me Moses Masaoka , 100; Jere Takahashi, Nisei/Sansei: Shifting Japanese American Identities and Politics (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1997), 89.

- ↑ Hosokawa, Nisei , 205; Annie Nakao, "Furor over memorial to Japanese Americans: Critics fight to remove name of man hailed as rights leader," San Francisco Chronicle July 7, 2000.

Last updated July 29, 2020, 5:37 p.m..

Media

Media