Fred Tayama

| Name | Masaru "Fred" Tayama |

|---|---|

| Born | July 15 1905 |

| Died | May 9 1966 |

| Birth Location | Hawaii |

| Generational Identifier |

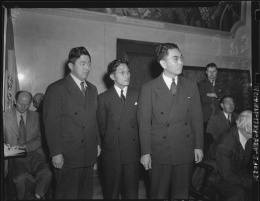

Businessman, Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) leader, beating victim at Manzanar. Fred Tayama (1905–66) was a JACL leader whose beating at Manzanar set off a chain of events leading to a riot/uprising at the camp.

Masaru "Fred" Tayama was born in Hawai'i on July 15, 1905, and graduated high school in central California, going on to attend the Armour Institute in Illinois before settling in Los Angeles in 1929. At Armour, he did experiments with early versions of television and aspired to be an electrical engineer, but as with many older Nisei who aspired to professional employment, was deterred by racism. After getting a job fixing radios in Little Tokyo, he opened the first of a chain of U.S. Café restaurants with his parents. Over the next decade, he became a successful entrepreneur and community leader in Little Tokyo. A member of the Japanese Union Church, he met his future wife Chiyoko Shiina there. The couple had a daughter in August 1931. He also served as president of the Los Angeles chapter of the JACL and chairman of the Southern District Advisory Council, which encompassed twenty chapters. Just prior to the war, he left the restaurant business and opened the Pacific Service Bureau, a legal services and insurance agency that was also very lucrative.

Like many of the early JACL leaders, he espoused a "100% American" philosophy, having renounced his dual citizenship in 1925 and vowing not to send his children to Japanese language schools (though he was himself fluent in Japanese). At the same time, he was known to have a regular golf date with the Japanese consul general. He also made some enemies in the community with his aggressive business style, becoming embroiled in a dispute with labor organizers over working conditions at his restaurants and being vilified in the pages of the Japanese American leftist newspaper Doho . Many also claimed that he charged Issei exorbitant prices for routine legal services and exploited his JACL position to secure business.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Tayama became the head of the Anti-Axis Committee, a swiftly formed Japanese American organization meant to demonstrate Nisei loyalty. A December 13th statement by Tayama on behalf of the committee read, "The United States is at war with the Axis. We shall do all in our power to help wipe out vicious totalitarian enemies. Every man is either friend or foe. We shall investigate and turn over to the authorities all who by word or act consort with the enemies." [1]

Despite his efforts to demonstrate "loyalty," Tayama and all other West Coast Japanese Americans were removed from their homes and sent to inland concentration camps, in Tayama's case to Manzanar. After representing Manzanar at a JACL conference in Salt Lake City, Tayama was attacked in his barracks room and severely beaten by six masked men on December 5, 1942. The subsequent arrest of Harry Ueno for the beating set off a chain of events that led to a mass riot/uprising that resulted in two inmates being shot to death by guards. (See Manzanar Riot/Uprising and Homicide in camp .) The following day, a gang went to the hospital where Tayama was recuperating to try to "finish him off"; he was hidden by hospital staff and eventually spirited out of Manzanar, along with other Nisei on the so-called "death list."

According to a report by Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS) researcher Morton Grodzins, Manzanar residents widely approved of Tayama's beating. In addition to being a suspected " inu ," his detractors pointed to his alleged labor exploitation and to allegations of various financial improprieties that victimized other Japanese Americans in the run up to mass removal. Class resentments were undoubtedly also a factor. [2]

After being evacuated to a Civilian Conservation Corps camp in Death Valley , he resettled in Colorado and taught Japanese classes at the United States Naval Intelligence Language School until 1946. He eventually returned to Los Angeles and opened Tayama Wholesale in 1947, a cut flower and orchid enterprise. He later became president of the Southern California Floral Association. He died on May 9, 1966. [3]

For More Information

Grodzins, Morton. " The Manzanar Shooting. " The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive. Bancroft Library, University of California. Call number BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder O10.04.

Hansen, Arthur A., and David A. Hacker. "The Manzanar Riot: An Ethnic Perspective." Amerasia Journal 2.2 (1974): 112-57.

Hayashi, Brian Masaru. ' For the Sake of Our Japanese Brethren': Assimilation, Nationalism, and Protestantism among the Japanese of Los Angeles, 1895-1942 . Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995.

Kurashige, Lon. Japanese American Celebration and Conflict: A History of Ethnic Identity and Festival, 1934-1990 . Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

Mori, Henry. "Fred's Bleakest Christmas Eve." Pacific Citizen , Dec. 19, 1958, A-4, A-14.

Tanaka, Togo. " A Report on the Manzanar Riot of Sunday December 6, 1942. " The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive. Bancroft Library, University of California. Call number BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder O10.12 (2/2).

Footnotes

- ↑ Arthur A. Hansen and David A. Hacker, "The Manzanar Riot: An Ethnic Perspective" Amerasia Journal 2.2 (1974): 148.

- ↑ Morton Grodzins report summarizes the many grievances large segments of the ethnic community had with Tayama, noting that they were widely believed, whether they were true or not. Grodzins, "The Manzanar Shooting" 2–3, 13–14, The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, University of California, call number BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder O10.04, accessed on Sept. 1, 2015 at http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b210o10_0004.pdf ; Hansen and Hacker, "The Manzanar Riot," 156; Lon Kurashige, Japanese American Celebration and Conflict: A History of Ethnic Identity and Festival, 1934-1990 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 84.

- ↑ Brian Masaru Hayashi, ' For the Sake of Our Japanese Brethren': Assimilation, Nationalism, and Protestantism among the Japanese of Los Angeles, 1895-1942 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995), 155; "Final Rites Held for Fred Tayama," Pacific Citizen , May 13, 1966, 1.

Last updated Sept. 20, 2015, 1:24 a.m..

Media

Media

![[Report on Manzanar strike/riot] [Report on Manzanar strike/riot]](https://encyclopedia.densho.org/front/media/cache/df/2b/df2b7759ffe9608c3d5d0688b8b2645e.jpg)