Manzanar riot/uprising

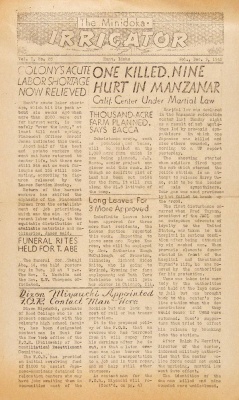

A December 1942 incident at the Manzanar camp that resulted in the institution of martial law at the camp and that culminated with soldiers firing into a crowd of inmates, killing two and injuring many. The incident was triggered by the beating of Japanese American Citizens League leader Fred Tayama upon his return from a meeting in Salt Lake City and the arrest and detention of Harry Ueno for the beating. Coming one year after the attack on Pearl Harbor, sensationalist coverage of the event inflamed anti-Japanese sentiment outside the camps. The episode exposed deep divisions within the inmate population and with the camp administration.

Background

For various reasons, Manzanar's was a divided population on the eve of the unrest. To some degree, the divisions predated the camp. Manzanar's population came mostly from Los Angeles, and tensions around Little Tokyo had been on rise prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor. According to Togo Tanaka , the English section editor of the Rafu Shimpo newspaper and later a key figure in the unrest, "several months before Pearl Harbor, the Japanese expression 'inu'... was being applied to some J.A.C.L. [Japanese American Citizens League] leaders" due to rumors that some were talking to the FBI and Office of Naval Intelligence. [1] After the attack on Pearl Harbor, further actions of JACL leaders aroused anger. Some formed the Anti-Axis Committee, which operated out of the Los Angeles JACL office and took a strong patriotic stand in an attempt to sway public opinion against drastic action towards Japanese Americans. Tokutaro Slocum , a leader of the committee, later boasted before the Tolan Committee that he turned in names of fellow Japanese Americans to the FBI. Fred Tayama, a local JACL leader and Los Angeles businessman, was accused of exploiting Issei fears in the weeks prior to the mass removal, by charging them exorbitant fees for simple services. In general, many Japanese Americans—particularly Issei and Kibei—objected to the JACL strategy of encouraging cooperation with the mass removal, viewing those who promoted such an approach as race traitors. [2]

Once in the camp, broken promises and high turnover of administrators stoked inmate frustrations. Manzanar had begun under the administration of the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA), a branch of the army, and later transferred to War Relocation Authority (WRA) administration. It had five managers/project directors in its first eight months of operation, and promises made under one administration were often broken by succeeding ones. In one example, WCCA manager Clayton E. Triggs promised inmates much higher salaries for work done in the camp than was actually implemented. Salary checks were also late, with the first ones not arriving for three months after the work had been completed. Many of the WRA administrators were disliked by inmates, with one in particular, Assistant Project Director Ned Campbell, drawing near universal scorn for his condescending and short-tempered approach. Inmates also widely believed that several staffers were stealing supplies such as sugar and selling them outside the camp on the black market. Campbell was among those suspected, accused by Harry Ueno, the popular leader of the Mess Hall Workers Union. For these and other reasons, animosity towards the administration—and by association, Japanese American inmates who worked with them—was high relative to other camps. [3]

Through the fall, a variety of occurrences added fuel to the smoldering resentments. Most block managers at Manzanar under WCCA administration were Issei or Kibei. But in line with WRA regulations that favored placing American citizen Nisei in leadership posts, the camp administration sought to install a community council whose membership would be limited to Nisei in place of the existing Block Leaders' Council. Many of the Nisei who sought leadership posts were associated with the JACL, including Tayama, who was elected chairman of the Manzanar Work Corps, and Tanaka, who headed the Commission on Self-Government. Pro-JACL Nisei in a coalition with Nisei leftists/Communists also formed the patriotic Manzanar Citizens Federation, which advocated working with the administration to improve camp conditions and allow Nisei to serve in the U.S. armed forces. Early meetings of the federation were contested by heated opposition from Joe Kurihara , an embittered Nisei World War I veteran who would become a leader among Manzanar dissidents. There was also a widespread belief that some of the JACL-aligned Nisei were acting as informers to the FBI. [4]

But the immediate precipitating event to the riot/uprising was Tayama's participation in a national JACL meeting in Salt Lake City in November. Among other recommendations adopted at the meeting, was one advocating that Nisei eligibility for the draft be restored. When Tayama returned to Manzanar, he was a marked man.

The Event

On Saturday night, December 5 at around 8 pm, Fred Tayama was attacked by a group of six masked intruders in his barracks room in Block 28. A young woman passing by heard the commotion and screamed, causing the attackers to disperse. An ambulance conveyed Tayama to the hospital, where he was treated for a cut scalp and other non-life threatening injuries. Though he could not positively identify his attackers, Tayama fingered Harry Ueno as one of the culprits. Ueno was taken into custody and questioned, then taken by Campbell outside the camp to the county jail in Independence. Two other suspects were also questioned through the night, but were released early the next morning.

The next morning a group of about 200 gathered at the Block 22 (Ueno's block) mess hall. The group met briefly and adjourned, deciding to arrange a larger meeting at 1 pm. The 1 pm meeting drew an overflow crowd of over 2,000 and spilled into a neighboring firebreak. At the meeting, angry speeches by Joe Kurihara and others called for Ueno's release under threat of a general strike. Prevailing sentiment was that Ueno's arrest had more to do with his accusations against Campbell than any role in the beating. Kurihara also called for the death of "inu" on a "death list" he had made. The meeting ended with the formation of a negotiating "Committee of Five" (CoF) who would be empowered to negotiate with Camp Director Ralph Merritt. The committee included Issei Sakichi Hashimoto, Kazuo Suzukawa, and Genji Yamaguchi; Kibei Shigetoshi Sam Tateishi, and Kurihara, who was named spokesman of the group. Merritt and John M. Gilkey, the acting chief of internal security, arrived as the meeting was breaking up, then returned to the administration building to await the CoF.

At about 1:30, the CoF along with a large crowd, arrived at the administration building. By that time, Captain Martyn L. Hall, commanding officer of the military police detail at Manzanar, had assembled a group of about twelve soldiers who had entered the camp and who stood guard at the administration building armed with machine guns. [5] Escaping from the unruly crowd, Merritt met with the CoF and they reached an agreement: Ueno would be brought back to the jail at Manzanar and would be tried at Manzanar; in return, the CoF would disburse the crowd and agree not to hold further demonstrations or to attempt to free Ueno. Kurihara spoke to the crowd, telling them they should disburse and reassemble at 6 pm. While they did not disburse immediately, they did disburse by 3 pm once the MPs moved back outside the camp. Ueno was brought back to Manzanar at about 3:30.

At 6:00 a crowd now consisting of some 2,000 to 4,000 people reconvened at Block 22's mess hall and the firebreak. The CoF announced the return of Ueno and attempted to resign, but the crowd would not allow them. After a few speeches—including Kurihara's further elaboration on the "death list" of fellow inmates headed by Tayama and also including alleged "inu" Tokutaro Slocum, Karl Yoneda , Togo Tanaka, and others—the crowd became more agitated and two groups formed, one to go after those on the "death list" starting with the hospitalized Tayama, the other to go to the camp jail to attempt to free Ueno.

Sometime after 6:30 a group of 50–75 people arrived at the hospital, armed with whatever weapons they had been able to find. They were held off at the door by inmate women hospital workers. Meanwhile head inmate doctor James M. Goto and other staff hid Tayama on the lower shelf of a bed and covered him with blankets. Believing that Tayama had been removed from the hospital already, Morse Little, the chief medical officer at Manzanar, decided to allow five representatives of the group to search the hospital. When the group failed to find Tayama, they broke off into smaller groups to go after others on the list. Most on the list had been tipped off and had gone into hiding and so were not found that night.

A larger group of some 500 arrived at the police station at around 6:50 with the intent of freeing Ueno. Arthur L. Williams, the assistant chief of internal security at Manzanar, met with the CoF, pointing out that they had breached the agreement from earlier that day. When Williams informed Merritt of the situation—which also saw inmate police having largely scattered out of fear for their lives—Merritt gave the okay to bring back MPs to restore order. The first group of MPs arrived at 7:15. As Williams met with the CoF—Merritt's attempts to get to the police station were stymied by the crowd—the crowd grew increasingly unruly, throwing stones and taunting the MPs. After Hall's addresses to the crowd after 8 pm failed to break it up, he decided that force would be necessary. At around 9:30, he ordered tear gas fired into the crowd. In the ensuing chaos, the crowd aimed a car sans driver toward the police station, causing MPs to open fire on it. Two other MPs, Privates Ramon Cherubini and Tobe Moore, fired into the crowd on their own initiative. As the crowd disbursed, several casualties of the shootings remained behind. Through the night, mess hall bells tolled continuously, various meetings were held, and several alleged "inu" were beaten.

Aftermath

When the dust had settled, one young man, 17-year-old James Ito of Los Angeles, had been killed by the gunfire; another, 21-year-old Jim Kanagawa of Tacoma, would die of injuries several days later. Nine others were shot but survived. [6]

Two groups of inmates subsequently left Manzanar. The first group consisted of those the administration considered responsible for the unrest, included Ueno, members of the CoF, and twenty others. These men were arrested and held in jails in Lone Pine and Independence, though ten were later returned to Manzanar. The other sixteen ultimately were sent to a newly established prison camp in Moab, Utah , administered by the War Relocation Authority, then transferred to another such camp in April 1943 in Leupp, Arizona. Most ultimately ended up at post-segregation Tule Lake when Leupp closed in December 1943.

The other group to leave the camp where those who had been threatened with violence, including JACL-associated figures such as Tayama, Tanaka, Slocum, and others, including several who had been attacked and injured on Sunday night. Initially housed in the MPs barracks and administration building, sixty-five refugees were moved to the Cow Creek camp adjacent to the Death Valley National Monument. The group, which included the families of some of the men, remained there until arrangements could be made for their resettlement outside the restricted area. Several ultimately ended up moving to Chicago.

Back at Manzanar, inmates organized anew. A group of 108 elected delegates—three from each block—formed and threatened a general strike unless Ueno and the others were released. Block managers also distributed black arm bands, which most inmates chose to wear. An informal strike slowed camp operations, such as the schools, which remained closed until January 10. Additional military police were added, and they patrolled the camp for a few days. But gradually, conditions in the camp calmed and operations returned to "normal" in January, as the MPs' presence gradually diminished.

A military investigation of the actions of the MPs in January 1943 exonerated them of any wrongdoing, concluding that Cherubini and Moore were justified in firing their weapons "because members of the mob were closing in and surging towards them." [7]

Legacy

Due in part to the timing of the riot/uprising, many contemporaneous external accounts characterized it as a pro-Axis revolt commemorating the one-year anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor. It was part of a raft of negative publicity about the incarceration that led to Congressional investigations that put the WRA on the defensive. The event—along with similar unrest in other camps—influenced the WRA in developing and implementing a policy to identify and segregate the "disloyal" inmates and to encourage the "loyal" to leave the camps and " resettle " in communities outside the West Coast.

Over the years, the riot/uprising has been analyzed numerous times by a range of scholars, and the varying interpretations of the event parallel the change in how the incarceration as a whole has come to be viewed. Contemporaneous investigations and analysis included reports from the WRA, particularly Community Analyst Morris Opler , and from Togo Tanaka, written for the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS). These various reports cited as the causes of the unrest the pre-existing frictions that existed between groups of inmates, the failures of camp administrators, and generational conflict between the Issei/Kibei and Nisei. In the 1970s, historians Gary Y. Okihiro and Arthur A. Hansen/David A. Hacker analyzed the event through a resistance framework. In 2001, Lon Kurashige introduced elements of class and gender studies to the analysis. Through the Oral History Program at California State University, Fullerton, Hansen has interviewed several other participants in or witnesses of the unrest, including Togo Tanaka, Ned Campbell, and Harry Ueno; an extensive interview with the latter was published in 1986. Eileen H. Tamura's biography of Joe Kurihara appeared in 2013.

For More Information

Secondary Sources

Cates, Rita Takahashi. "Comparative Administration and Management of Five War Relocation Authority Camps: America's Incarceration of Persons of Japanese Descent during World War II." Diss., University of Pittsburgh, 1980.

Embrey, Sue Kunitomi, Arthur A. Hansen, and Betty Kulberg Mitson. Manzanar Martyr: An Interview with Harry Y. Ueno' . Fullerton: Oral History Program, California State University, Fullerton, 1986.

Hansen, Arthur A., and David A. Hacker. "The Manzanar Riot: An Ethnic Perspective." Amerasia Journal 2.2 (1974): 112-57.

Hayashi, Brian Masaru. Democratizing the Enemy: The Japanese American Internment . Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004.

Kurashige, Lon. "Resistance, Collaboration, and Manzanar Protest." Pacific Historical Review 70.3 (August 2001): 387–417.

Okihiro, Gary Y. "Japanese Resistance in America's Concentration Camps: A Re-evaluation." Amerasia Journal 2.1 (1973): 20-34.

Tamura, Eileen H. In Defense of Justice: Joseph Kurihara and the Japanese American Struggle for Equality . Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Unrau, Harlan D. The Evacuation and Relocation of Persons of Japanese Ancestry During World War II: A Historical Study of the Manzanar War Relocation Center . Historic Resource Study/Special History Study, 2 Volumes. [Washington, DC]: United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1996.

Primary Sources Available Online

Adams, Lucy. " Notes on Manzanar Disturbances, 1942 ." The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, University of California. BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder O10.00. [Journal by interim education supervisor Adams from her arrival on Nov. 17 to Dec. 10. 14 pages.]

Grodzins, Morton. " The Manzanar Shooting, Jan. 10, 1943. " The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, University of California. BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder O10.04. [Report by JERS researcher. 46 pages.]

Tanaka, Togo. " A Report on the Manzanar Riot of Sunday December 6, 1942. " The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, University of California. BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder O10.12 (2/2). [Written shortly after the events for JERS by a key participant while he was at the Cow Creek camp in January 1943. 103 pages.]

Letter by Ralph Merritt to his Aunt Luella , Dec. 25, 1942. Reprinted in Common Ground 3.3 (Spring 1943): 86–88.

Footnotes

- ↑ Literally "dog" in Japanese, "inu" in this context means one suspected of being an informer.

- ↑ Togo Tanaka, "A Report on the Manzanar Riot of Sunday December 6, 1942," The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, University of California, call number BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder O10.12 (2/2), accessed on July 19, 2014 at http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b211o10_0012_2.pdf , quote from page 7; Deborah K. Lim, "Research Report Prepared for the Presidential Select Committee on JACL Resolution #7 (aka 'The Lim Report'), 1990; Paul R. Spickard, "The Nisei Assume Power: The Japanese-American Citizen's League, 1941-1942," Pacific Historical Review 52 (May 1983), 158; Morton Grodzins, "The Manzanar Shooting," The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, University of California, call number BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder O10.04, accessed on Sept. 1, 2015 at http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b210o10_0004.pdf , pages 2–3, 13–14.

- ↑ For more on inmate/keeper tensions at Manzanar, see Rita Takahashu Cates, "Comparative Administration and Management of Five War Relocation Authority Camps: America's Incarceration of Persons of Japanese Descent during World War II" (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pittsburgh, 1980), 223–25, 230–41; Arthur A. Hansen and David A. Hacker, "The Manzanar Riot: An Ethnic Perspective," Amerasia Journal 2.2 (1974): 141.

- ↑ Lon Kurashige, "Resistance, Collaboration, and Manzanar Protest," Pacific Historical Review 70.3 (August 2001), 391–92; Tanaka, "A Report on the Manzanar Riot," 47–53. As it turned out, at least two of the suspected "inu"—Tayama and Tanaka—were in fact FBI informants. See Harlan D. Unrau, The Evacuation and Relocation of Persons of Japanese Ancestry During World War II: A Historical Study of the Manzanar War Relocation Center , Historic Resource Study/Special History Study, 2 Volumes. ([Washington, DC]: United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1996), 492–93.

- ↑ The 322nd Military Police Escort Guard Company that Hall led guarded the perimeter of the camp but did not normally enter the camp. Security within Manzanar was handled by an inmate police force under the direction of Gilkey and his deputy, Arthur L. Williams.

- ↑ For a list of those shot, see Unrau, The Evacuation and Relocation , 487–88.

- ↑ Unrau, The Evacuation and Relocation , 519–20.

Last updated Nov. 18, 2020, 8:36 p.m..

Media

Media