Segregation

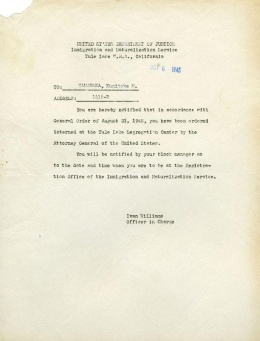

The term "segregation" when applied specifically to the history of Japanese Americans' wartime exclusion from the West Coast and incarceration is a term used to describe the process by which the War Relocation Authority (WRA) tried to separate "loyal" from "disloyal" Nikkei in response to critics who believed the unrest in the "War Relocation Authority" camps was being caused by a small number of "disloyal" agitators. The unintended consequences of a badly administered, poorly conceptualized plan led to the militarization and inhumane overcrowding of Tule Lake , the camp designated the "segregation center," increased protest and civil disobedience among the incarcerated population at Tule Lake, increased questions about civil and constitutional rights abuses of the incarcerated Nikkei, and no reduction in outside critics who believed every form of protest against civil rights abuses was a simple sign of Japanese American disloyalty.

Isolation Centers and the Beginnings of Segregation

Nikkei voiced their frustrations with living conditions as well as their lack of constitutionally protected rights throughout the first year of the war. Multiple strikes, mass protests, and what some called "riots" erupted in places like Santa Anita , Manzanar , Poston , and Gila River . The WCCA and the WRA tried to manage the unrest by removing individuals whom administrators believed may have led or organized the disturbances, and relocating them to other facilities. In response to the August 1942 unrest at Santa Anita, those identified as "troublemakers" were transferred to Tule Lake, not yet designated an official segregation facility. Later, in December, the WRA experimented with more formal ways of isolating individuals they had identified as "troublemakers."

The War Relocation Authority first began segregating Nikkei in response to the " riot " at Manzanar. The WRA used what it called a "rehabilitation" center in Moab , Utah, first, but soon began using what the WRA called an "isolation center" in Leupp , Arizona. These facilities were used to house men whom the WRA had identified as "troublemakers," men whom the WRA wanted removed from the general population of the larger "relocation centers" for anything from organized efforts to address grievances to trivial conflicts with WRA administrators.

Expanding Segregation

Protest against government mistreatment of Nikkei became widespread and organized in response to the joint loyalty registration program administered by the War Department and the WRA in January 1943. Individuals used the loyalty registration questionnaire in many cases as their first opportunity to formally protest their unconstitutional wartime treatment. Seventeen percent of all registrants and approximately 20 percent of all Nisei answered loyalty questions with at least one "no" and/or qualified their answers with statements of protest about their lack of rights. Most shocking to WRA administrators was the sharp rise in applications for repatriation and expatriation to Japan. Late the previous year only 2,255 individuals had requested repatriation to Japan. By 1943 this number shot over 9,000. Most new applicants were citizens. The trend continued into 1944 when the number of re/expatriation requests topped out at nearly 20,000, or 16 percent of the total evacuated population.

By March 1943 it became clear to Dillon Myer , director of the WRA that the continued indefinite incarceration of Nikkei in the camps was resulting in a rapid deterioration of morale and loyalty. He argued for large-scale resettlement of "loyal" Nikkei outside of the camps and pushed Secretary of War Henry Stimson to lift military exclusion for the West Coast. Stimson and Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy opposed Myer's suggestion that the military reopen the West Coast to Nikkei for two reasons. First General John DeWitt along with California politicians and private groups like the Native Sons of the Golden West remained steadfast in their opposition to Nikkei returning to the West Coast. Second, if the government were to admit that they could, through a fairly simple bureaucratic process, identify who among the Nikkei population was loyal and who was disloyal in order to allow some to return to the West Coast, it might undermine the original argument for complete removal of Nikkei from the West Coast in the first place. Instead, Stimson demanded that the WRA adopt a segregation policy based on the argument that unrest in the camps had been caused by a few "troublemakers." Myer agreed reluctantly, knowing that segregating individuals who were ostensibly "loyal" from "disloyal" would be extremely problematic.

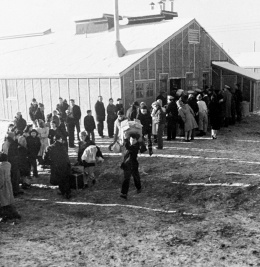

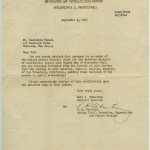

Tule Lake was the camp designated as the "segregation center" because it was the camp where the numbers of individuals who answered the loyalty questions with " no-no " had been the highest. Midway through 1943, the WRA began the process of transferring "loyal" inmates from Tule Lake for reassignment to other WRA camps in exchange for the transfer of roughly eighteen thousand individuals from the other nine WRA camps who had been labeled "disloyal" for giving negative responses to the loyalty questionnaire, for requesting repatriation to Japan, and/or for requesting the right to renounce their U.S. citizenship. The conditions at Tule Lake deteriorated rapidly, caused by conditions related to severe overcrowding and the punitive administration of Ray Best, the original director of Moab, and later Leupp, transferred to Tule Lake to administer over the segregation center. Best continued the practice of arresting "troublemakers" and imprisoning them without due process, this time in an internal jail called the "stockade." This practice was only brought to an end when American Civil Liberties Union lawyer Ernest Besig threatened the WRA with embarrassing publicity regarding its questionable use of the "stockade" along with his plans to file habeas corpus suits on behalf of the inmates still isolated in Tule Lake's internal prison.

In response to continued unrest, President Roosevelt signed a bill that would permit Nisei to renounce their citizenship. This act was signed into law in July of 1944. The unprecedented act reinforced the belief some Nikkei held that even U.S.-born citizen Nisei did not have a future in the United States. A total of 5,589 Japanese Americans renounced their U.S. citizenship, ninety-eight percent of whom were segregated at Tule Lake. The pressure became so intense at Tule Lake that seventy percent of adult American citizens renounced their citizenship.

By the middle of 1944, it became clear that the unconstitutional treatment of Japanese Americans, the harsh living conditions in the camps, and the seemingly arbitrary segregation of Nikkei into "loyal" and "disloyal" had embittered thousands of individuals who had been loyal to the U.S. before the war but who became extremely critical of the United States near the war's end. In clear admission of the failed policy of segregation and the lack of a clear connection between "loyalty" and the various ways in which Nikkei had chosen to register their dissatisfaction with their wartime treatment (including negative answers to the loyalty questionnaire, requesting repatriation, and renunciation of citizenship), the WRA stopped transferring individuals to Tule Lake mid-way through 1944. Instead administrators were instructed to treat new cases of Nisei acts of "disloyalty" as attempts to avoid the draft, which had been reinstated for Nisei in February 1944, despite their continued incarceration in the camps.

Aftermath and Legacy of Segregation

When the war ended in August 1945, Nisei who had retained their U.S. citizenship were able to leave Tule Lake, but those who had renounced their citizenship and others who had requested repatriation to Japan were not free to leave. A total of 3,000 Issei and 1,327 Nisei were identified for deportation to Japan. Many of those slated for deportation had renounced their citizenship and/or requested repatriation under duress and sought to reverse their decisions with the assistance of civil rights attorney Wayne M. Collins . With his assistance, the numbers of individuals deported to Japan after the war was reduced to 1,327. The legal battle to restore the citizenship of Nisei who renounced lasted twenty years. The divisions created by segregation during wartime still persist, though scholars and some segments of the community have started to recognize the civil rights basis of much of the wartime resistance that led so many Nikkei to be labeled "disloyal" during the war years.

For More Information

Burton, Jeff, et. al. "Citizen Isolation Centers," In Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites .

Drinnon, Richard.

Keeper of Concentration Camps: Dillon S. Myer and American Racism

.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

Lyon, Cherstin. Prisons and Patriots: Japanese American Wartime Citizenship, Civil Disobedience, and Historical Memory . Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011.

Myer, Dillon S. Uprooted Americans: The Japanese Americans and the War Relocation Authority During World War II . Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1971.

National Park Service. Tule Lake Unit.

Omori, Emiko. Rabbit in the Moon . Hohokus, N.J.: New Day Films, 1999.

Robinson, Greg. A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in North America . New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

Weglyn, Michi. Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America's Concentration Camps . New York: Morrow Quill, 1976.

Last updated Jan. 16, 2024, 3:20 a.m..

Media

Media