Gila River

| US Gov Name | Gila River Relocation Center |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | Concentration Camp |

| Administrative Agency | War Relocation Authority |

| Location | Rivers, Arizona (32.1667 lat, -111.8667 lng) |

| Date Opened | July 20, 1942 |

| Date Closed | November 16, 1945 |

| Population Description | Held people from Los Angeles, Sacramento, and Amador Counties; 3,000 were sent from southern San Joaquin Valley; also held 155 Japanese immigrants from Hawaii. Canal Camp housed people from the Turlock Assembly Center and San Joaquin Valley, while Butte Camp housed people from the Tulare and Santa Anita Assembly Centers. |

| General Description | Located in a valley within the Gila River Indian Reservation in Pinal County, 50 miles south of Phoenix, 3 miles north of the Sacaton Mountains. Consisted of two separate camps: Canal and Butte, located 3.5 miles apart between irrigation canals. The 16,500 acres are in an arid desert valley with average summer temperatures over 100 degrees. Vegetation includes mesquite, creosote, and cactus. |

| Peak Population | 13,348 (1942-11-30) |

| National Park Service Info | |

Rivers Relocation Center is one of the two camps located on American Indian Reservations, both of which were located in Arizona. Known more popularly as Gila River, this concentration camp held over 13,000 inmates, most of whom were from California. This camp was known for its baseball team, the Gila River Eagles, its prolific produce that fed most of the camps, and for being visited by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt .

Site Background

In early March 1942, Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier wrote to the Secretary of War proposing that the Department of Interior be authorized to work with the Japanese Americans who would be removed from the western states as a result of Executive Order 9066 . He noted that the Department had resources of land, welfare and recreational specialists, as well as experience working with an ethnic minority, the American Indians. Collier felt that Japanese Americans would be effective workers for reclamation and agricultural projects under the jurisdiction of the Department of Interior. The War Department ultimately selected the Gila River Indian Community and the Colorado River Indian Community, both reservations in Arizona, as sites for two of the ten concentration camps. Although Collier lobbied for the Office of Indian Affairs to administer both of these camps, partly because of the infrastructure that would be built at the War Department's expense and because of the labor provided by the internees, the War Department only authorized Collier to have jurisdiction over the Poston Relocation Center at Colorado River. [1] The Bureau of Indian Affairs under Collier sought to limit the War Relocation Authority (WRA) to lands uncultivated, but the WRA, well aware of the need for the camps to cultivate their own food, took over acreage being cultivated for the tribe's own agricultural pursuits. [2]

The Akimel O'otham and Maricopa Indians of the Gila River Indian Community, living on a reservation created and approved by Congress in 1859, formed an Indian Reorganization Act government in 1936. Nonetheless, the elected Tribal Council's work was still subject to the oversight of the Office of Indian Affairs within the Department of the Interior. When the Council was notified in May 1942 that the WRA was going to lease 17,000 acres of its land for two camps, one by a canal and another by the Sacaton Butte, the members rejected the proposed agreement in favor of having the community vote. They once more rejected the agreement in September 1942, even though the camps were nearly complete. Only in October did the council narrowly vote to authorize the contract. Although some community members were hired to work in the camps as guards, as workers with the livestock, or in the war production factories, Gila River community members overall were not given priority for employment in constructing the camps or working within the camps. [3]

The concentration camp was named Rivers after Jim Rivers, the first Akimel O'otham killed in the First World War. It was divided into two camps: Camp One was named Canal, and Camp Two was named Butte, based on their locations. Butte had a hospital and Canal had a fire station, and both had elementary and high school facilities. The first inmates arrived at Canal in mid-July 1942 as volunteers to help prepare the camp in advance of the other inmates, most who came from the Central California regions and were previously held at Turlock Assembly Center or had been living in the restricted area. The inmates in Canal exceeded the camp's capacity by the time Butte Camp opened in mid-August 1942, with Canal built for 4,800 inmates and Butte built for 10,000 inmates. Butte's residents were primarily from the Tulare and Santa Anita Assembly Centers, although there were inmates from Hawai'i. [4]

The WRA Camp

Climate and Population

Those who were brought to the Gila River concentration camp recall that they boarded a train with all the shades pulled down and were not told where they were going. Masaji Inoshita, a young man in his twenties at the time, remembers that when he finally realized they were being brought to Arizona, he felt great fear. European-American farmers in Maricopa County, Arizona, had mounted a strong anti-alien movement from 1934 to 1935, seeking to force out all non-citizen, particularly Japanese, farmers from the state. [5]

The inmates also arrived during the height of the summer heat of Arizona. July 1942 recorded 25 days over 105 degrees, while August had 23 days over 100 degrees, six of those over 105. The barracks were not insulated. Some inmates installed swamp coolers—some homemade—into their barracks. Most inmates dug beneath their barracks to find escape from the heat, and many additionally created concrete fish ponds for both decorative purposes and to keep the air cooler in their barracks. Because the barracks all looked similar, people individualized their living quarters by decorating doorway areas with cans, river stones, and pieces of glass. [6]

Throughout Rivers' operation, over 16,000 Japanese Americans lived in the camp; the population figures for the camp are not consistent, but one report states that the largest number of Rivers' inmates at one time totaled 13,348. In a report from February 1943, close to 55% of 13,165 total inmates were male, and 62% were U.S. citizens by birthright. After the controversy over the "loyalty questionnaire" , about 1,800 inmates, 75% of whom were perceived as disloyal to the US government because they refused to disavow loyalty to the Japanese emperor, were relocated to the Tule Lake concentration camp. The other 25% relocated in order to keep their families intact, and some Rivers' inmates also relocated to the Crystal City Detention Center where families of enemy aliens interned by the Department of Justice were allowed to reunite. [7]

Governance and Employment

By February 1943, 7,649 (58% of the inmates) worked for wages in the camp with 879 men and women working on 820 acres growing produce, 450 working in war production, and the majority working directly for the WRA in staff positions for the mess hall or hospital, the elementary and high schools, and as support staff for the administrators. Only those working in the camouflage net factory received a higher wage than the paltry WRA scale. [8] In Fall 1942, just months after the farming began in July, the agricultural division had already produced 242,000 pounds of produce, 64,000 pounds of which were sent to Poston and the rest consumed at Rivers. In addition to cultivating vegetables, the camp had a dehydration center to preserve vegetables, which was later replaced with a cannery. The inmates had to be trained how to grow produce in the dry and hot conditions of Central Arizona, which was a much different climate than Central California. The success of the agricultural operations only increased: in fiscal year 1944, for example, Gila River was responsible for sending over four million pounds of produce for consumption to eight of the other WRA camps. [9]

The camp had a formal "self-governing" structure with a council consisting of representatives from each block. Each block had its own council for specific issues relating to that block, but these councils did not have formal relations with the WRA administration. The WRA was not comfortable with the Issei men who primarily led the block councils because of concerns that the Issei would be more pro-Japanese and influence the Nisei in the camp. The WRA's tendency to work with Nisei contributed to intergenerational tensions within the camp.

At first the camp went through a series of project directors. E.R. Smith served as the initial director, then was succeeded temporarily by E. R. Fryer in late September and October 1942, followed by Louis J. Korn in November 1942. Leroy H. Bennett eventually was appointed director in December 1942 and remained through July 31, 1945. Douglas M. Todd took over as director for the remaining three and a half months of the camp's operation. The project director administered policy handed down from the WRA national office, and also interacted with local communities, many of which resented the presence of the Japanese Americans in their vicinity. Indeed, the governor of Arizona had protested the two camps located in the state. [10]

"Coddling" and Military Service

The local press accused the Gila River inmates of not being patriotic enough to contribute to the cotton harvest. One local newspaper in October 1942 charged that only one of 100 inmates volunteered to pick cotton, that the camps were taking teachers and hurting the Arizona public schools, that inmates were receiving milk before Arizonans were, and that the WRA was giving inmates hunting permits free of charge. These charges reflected the press in other areas that accused the federal government of "coddling" the Japanese Americans in the camps. In response to these accusations, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited Gila River in April 24, 1943, to tour the facilities, highlighting the work the inmates were doing for the war effort in the camouflage net and ship model factories. Charles Kikuchi , who had been forced by the evacuation orders to leave UC Berkeley and was collecting data for the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study , noted that the First Lady sipped a glass of milk in the mess hall and remarked that it was sour—subtly responding to the media reports that the inmates were receiving better quality rations than other Americans. [11]

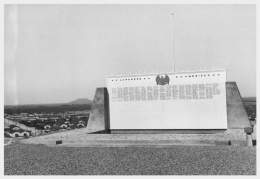

The social life in the camps was affected by the lack of privacy among people living in such close quarters. In addition to tensions between the first generation Issei and second generation Nisei, there were tensions between Kibei who had returned to Japan for their education and the Nisei. Those who volunteered for the U.S. Military Intelligence Service in 1942 learned that the families they had left behind when they left suddenly in the middle of the night from the camp were ostracized by most of the other families. When Japanese Americans were allowed to register for the draft, 994 Nisei men from Gila River ultimately left their families behind to serve in the U.S. Army. Some of the Nisei women signed up with the women's auxiliary corps as well . [12] Issei at Gila River later built a memorial in honor of their children serving in the U.S. military during World War II that overlooks the site of Butte Camp. Among the names on the memorial is that of Kazuo Masuda , a Nisei war hero whose family was at Gila River.

In 1943, the WRA began intensifying its efforts to place Japanese Americans in jobs outside of the western states. Many of these jobs were in manufacturing industries hit by the wartime labor shortage. Although over 50% of the Rivers inmates had indicated a willingness to be relocated on a Wednesday in April 1943, news from the Pacific front of Japanese soldiers executing United States soldiers resulted in an overnight reversal—fear of violence and harassment resulted in a majority of Japanese Americans not being willing to leave Rivers. [13]

Camp Life and Community

With time, the inmates created some semblance of community for themselves, despite the continual reminder that their freedom and rights had been greatly circumscribed as a result of incarceration. Even though inmates at Gila River were allowed more leeway than those at other camps to move beyond the borders of the camp, they were expected to request permission to go to into towns and required to check in upon returning. A camp newspaper, the Gila News-Courier , kept people informed of events and camp news. Events included meetings for the Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, women's clubs, theater groups, and athletics. Inmates could attend Buddhist services in camp as well as several Christian services. Students attended elementary and high school in both Rivers and Butte. [14]

The camp administration hired inmates to assist with recreational activities including movie nights or athletic leagues, and some of the groups were organized by the inmates themselves such as performances of traditional Japanese plays or the offering of traditional Japanese dance lessons. While the youth participated in club activities, attended schools, and played athletics, the recreation department also offered wood carving and crafts classes for the older Issei. The Issei women were involved in crafts and dances, and the older Issei males found other ways to keep themselves occupied. Some gathered ironwood from the desert and made carvings from the hard wood. Others created furniture from scrap lumber, including shelves, tables, and even dressers. Scrap metal was twisted into hangers or fashioned into tools. [15]

A major pastime in the camps as well as outside the camps was baseball. Kenichi Zenimura , a Japanese-born professional baseball player in the Central Valley Fresno Nisei League and founder of the Nisei Baseball League throughout California, was incarcerated at Gila River. Zenimura coached the high school baseball team, the Gila River Eagles, and organized a 32-team baseball league. He and his sons built a baseball field complete with bleachers to sit 6,000 spectators, right next to the high school grounds in Butte Camp. The Eagles invited the three-time state high school baseball champions, the Tucson Badgers to a game at Gila River. The Tucson coach, Hank Slagle, accepted this invitation. On April 18, 1945, the Eagles beat the Badgers 11-10; more importantly, however, is that after the game the players from both teams shared a meal and hung out together. [16]

Most of the interaction with European Americans took place in interactions with the War Relocation Authority administrators or supervisors at work. Interactions with the members of the Gila River Indian Community also occurred, but not on a regular basis for the most part. [17]

Closing and Aftermath

Many of Japanese Americans who remained at Rivers when the closing of the camp was announced in early 1945 were afraid to return to California. Threats had been made against their return, and even the WRA discouraged them from resettling in California. Older Japanese Americans who had nowhere to go after being uprooted from California had asked the community if they could remain, but were told they could not remain on Gila River Indian Community land. Some Japanese Americans who lived outside the military zone in Arizona provided housing and even employment for some of these families and individuals until many returned back to California. Butte Camp was closed September 28, 1945, Canal Camp was closed November 10, 1945, and Gila River Relocation Center completely shut down on November 16, 1945. [18]

Upon closing, inmates left piles of makeshift furniture, dishes, and other items behind. The Gila River Indian Community members salvaged what they could from those items, but did not benefit from any of the major structures or infrastructure that had been constructed for the camp. Even the piping that provided running water and the wiring that provided electricity to the camps were removed, leaving the broken concrete foundations behind, even while the reservation lacked those same resources. The WRA refused to spend the funds it would cost to clean up these foundations, which rendered the land unviable for Gila River Indian Community use. The WRA also did not fulfill the terms of the contract with Gila River Indian Community because it did not cultivate the 8,500 acres of land as it had promised to do in lieu of rent. [19]

Since the closure of the camps, the Japanese American community in Phoenix has maintained positive relations with the Gila River Indian Community, primarily through the efforts of Mas Inoshita. The Gila River Indian Community verbally agreed to not build or utilize the former camp sites unless they absolutely had to, and this promise has been maintained to this day. In 1996, community members, scholars, and artists worked together to explore the experiences of Japanese Americans imprisoned in Arizona. Playwright Lane Nishikawa met with former inmates and developed a play, "Gila River," that was performed by local community members at the Gila River Indian Community. Some of the Gila River Indian Community members shared their memories of the concentration camp, but a formal oral history project to preserve those memories did not commence until 2008.

Because the Gila River Indian Community maintains sovereignty over its land, which they privately own, visitors may not visit the former sites unless they have applied for and received a permit from the community and may be cited for trespassing; often this permission is only granted to individuals who can prove they are descended from former inmates.

For More Information

Jeffery F. Burton, Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord, and Richard W. Lord, Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites . Western Archeological and Conservation Center, National Park Service, 1999, 2000.

Enduring Communities Arizona . This site contains excerpts from oral histories of those interned at Gila River as well as a full-length video about Masaji Inoshita's World War II experiences, "Lessons in Loyalty" under Educator Materials.

Arthur A. Hansen. "Cultural Politics in the Gila River Relocation Center 1942-1943," Arizona and the West Vol. 27, No. 4 (Winter 1985): 327-362.

Arthur A. Hansen. "The Evacuation and Resettlement Study at the Gila River Relocation Center, 1942-1944." Journal of the West 38:2 (April 1999): 45-55.

Valerie Jean Matsumoto. "Shikata Ga Nai: Japanese American Women in Central Arizona, 1910-1978." Honors thesis, Arizona State University, May 1978.

Nisei Baseball Reunion Project. 2000. Diamonds in the Rough: Zenimura and the Legacy of Japanese-American Baseball . 35 min.

Rick Noguchi, ed. Transforming Barbed Wire: The Incarceration of Japanese Americans in Arizona during World War II . Phoenix, AZ: Arizona Humanities Council, 1997.

Andrew R. Russell, "Arizona Divided," in Brad Melton and Dean Smith, eds. Arizona Goes to War: The Home Front and the Front Lines During World War II . Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2003.

Spicer, Edward H., Asael T. Hansen, Katharine Luomala, and Marvin K. Opler. Impounded People: Japanese Americans in the Relocation Centers . Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Interior, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1946. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1969.

Bill Staples, Jr. Kenichi Zenimura: Japanese American Baseball Pioneer . NY: McFarland & Co., 2011.

Orit Tamir, Scott C. Russell, Karolyn Jackman Jensen, Shereen Lerner. Return to Butte Camp: A Japanese American World War II Relocation Center . Bureau of Reclamation, Arizona Projects Office, 1993.

Footnotes

- ↑ John Collier to the Secretary, March 4, 1942, RG 75, 180 H, Box 3; Milton S. Eisenhower to John H. Collier, San Francisco, Telegram, April 23, 1942, Bureau of Indian Affairs, National Defense Program Records Relating to the War Relocation Authority, National Archives, Washington, D.C., Box 3.

- ↑ William Zimmerman Jr. to John H. Collier, April 3, 1942, Bureau of Indian Affairs, National Defense Program Records Relating to the War Relocation Authority, Box 3; William Zimmerman Jr. to Milton S. Eisenhower, April 3, 1942, Bureau of Indian Affairs, National Defense Program Records Relating to the War Relocation Authority, Box 3.

- ↑ Orit Tamir, Scott C. Russell, Karolyn Jackman Jensen, Shereen Lerner, Return to Butte Camp: A Japanese-American World War II Relocation Center (Bureau of Reclamation, Arizona Projects Office, 1993).

- ↑ Tamir, et al., Return to Butte Camp .

- ↑ Author interview with Masaji Inoshita, Japanese Americans in Arizona Oral History Project , Sep 15, 2003; Masakazu Iwata, Planted in Good Soil: A History of the Issei in United States Agriculture (NY: Peter Lang, 1992).

- ↑ John C. Douglas to L. H. Bennett, March 11, 1943. War Relocation Authority, Subject Classified Files 1942-46, Gila River Relocation Center, National Archives, Washington, D.C., Box 130; communication with Masaji Inoshita on tour of Butte camp site, October 2003.

- ↑ Due Process: Americans of Japanese Ancestry and the United States Constitution 1787-1994 (San Francisco: National Japanese American Historical Society), 54-55; L.H. Bennett to Yoshika Takagi, Forum on Japanese Americans, Feb 4 1943, RG 210, Box 130; Tamir, et al., Return to Butte Camp .

- ↑ L.H. Bennett to F. de Amat, May 6, 1943, Box 146, War Relocation Authority, Subject Classified Files 1942-46, Gila River Relocation Center; "Camouflage Net Factory: History Procedure and Status as of March 31, 1943," n.s., n.d., War Relocation Authority, Subject Classified Files 1942-46, Gila River Relocation Center Box 146; Thomas Reynolds "Camouflage Net Factory," n.d., War Relocation Authority, Subject Classified Files 1942-46, Gila River Relocation Center, Box 146. Over 500 men and women assembled camouflage nets, receiving 48 cents per every 100 square foot of net. The average wage for these workers was $9.20 a day. There were also camouflage net factories at Manzanar and Poston.

- ↑ L.H. Bennett to Yoshika Takagi, Forum on Japanese Americans, Feb 4 1943, War Relocation Authority, Subject Classified Files 1942-46, Gila River Relocation Center, Box 130; Grant Shikawa to David A. Rogers, Nov 11, 1942, War Relocation Authority, Subject Classified Files 1942-46, Gila River Relocation Center, Box 146; David A. Rogers to Paul Morton, Jun 9 1944, War Relocation Authority, Subject Classified Files 1942-46, Gila River Relocation Center, Box 146.

- ↑ Douglas M. Todd, "History Covering Period From August 1, 1945 to November 15, 1945," Gila River Relocation Center, Rivers, Arizona, Office of the Project Director, Bancroft Library, at http://content.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt5b69n7cz&query=&brand=calisphere ; "Osborne Spurns Plan to Dump Enemy Aliens," Arizona Republic March 1, 1942; John C. Henderson to William M. Hugo, Sep 15, 1942, War Relocation Authority, Subject Classified Files 1942-46, Gila River Relocation Center, Box 148.

- ↑ "Stewart Appeals to WRA Against Taking Arizonans' Milk for Interned Japanese," Clipping from Maricopa Democrat , Oct 2, 1942, War Relocation Authority, Subject Classified Files 1942-46, Gila River Relocation Center, Box 130; I read this in Charles Kikuchi's diary kept for the Japanese Evacuation and Relocation Survey at the Bancroft Library in UC Berkeley.

- ↑ Author interview with Masaji Inoshita, Japanese Americans in Arizona Oral History Project, Sep 15, 2003; Tamir, et al., Return to Butte Camp .

- ↑ Hugo W. Wolter to L. T. Hoffman, April 23, 1943, War Relocation Authority, Subject Classified Files 1942-46, Gila River Relocation Center, Box 130.

- ↑ Tamir, et al., Return to Butte Camp .

- ↑ Tamir, et al., Return to Butte Camp .

- ↑ Bill Staples, Jr., Kenichi Zenimura: Japanese American Baseball Pioneer (NY: McFarland & Co., 2011); Nisei Baseball Research Project, "A Model of American Sportsmanship: Tucson High Badgers vs. Butte High Eagles".

- ↑ Interview with Arlene Johns, Japanese Americans in Arizona Oral History Project, Aug 1, 2006; Interview with Tom Koseki, Japanese Americans in Arizona Oral History Project, June 23, 2008.

- ↑ Interview with Masaji Inoshita, Sep 15, 2003, Japanese Americans in Arizona History Project; Tamir, et al., Return to Butte Camp .

- ↑ Tamir, et al., Return to Butte Camp .

Last updated Jan. 18, 2024, 4:32 p.m..

Media

Media