Poston (Colorado River)

| US Gov Name | Poston Relocation Center |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | Concentration Camp |

| Administrative Agency | War Relocation Authority |

| Location | Parker, Arizona (34.1500 lat, -114.2833 lng) |

| Date Opened | June 2, 1942 |

| Date Closed | November 28, 1945 |

| Population Description | Held people from Arizona, Oregon, and Washington. Salinas, Santa Anita, and Pinedale Assembly Centers in California as well as Mayer Assembly Center, Arizona, sent their populations here. |

| General Description | Located at 320 feet of elevation in southwestern Arizona on the Colorado River Reservation in Yuma County (now La Paz), 12 miles south of the town of Parker. The Colorado River runs 2 1/2 miles to the west. The 71,000 acres in the lower Sonoran desert are near the California border. The harsh climate featured hot and humid summers and cold winter nights. Dust was a constant problem. |

| Peak Population | 17,814 (1942-09-02) |

| National Park Service Info | |

Poston was a War Relocation Authority (WRA) concentration camp located in southwestern Arizona near the town of Parker, close to the border with California. As with Manzanar , it received many inmates directly from their homes rather than through the intermediary step of an " assembly center ." The most populous camp until Tule Lake was turned into the segregation facility , Poston was located on an Indian reservation, and until 1943, was jointly operated with the Office of Indian Affairs. The "Poston Strike" of November 1942 was one of the largest and most successful acts of resistance to WRA control, ending in a negotiated settlement that gave the strikers much of what they had demanded.

Geography and Prewar History

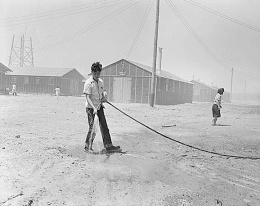

Poston was named after Charles D. Poston, a noted figure in early Arizona history who was also the first Superintendent for Indian Affairs in Arizona. Officially designated the "Colorado River Relocation Center," it was located in Yuma County (today La Paz County), Arizona, roughly twelve miles south of Parker, and three miles east of the Colorado River. Located in the Sonoran desert near sea level, Poston was extremely hot, with temperatures well over 100 degrees in the summer, and due to the proximity of the Colorado River, much more humid than might be expected from its desert location. In the winter, cooler weather prevailed, with nighttime temperatures sometimes dropping to freezing and below. The fine silt soil of the area was easily blown about by the wind; high winds and dust storms were not uncommon, adding to the difficulties of living in Poston. [1]

The WRA Camp

Population and Layout

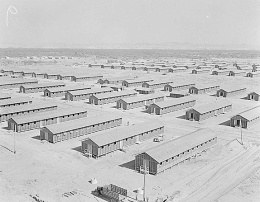

The Colorado River Indian Reservation, within which Poston was built, was established in 1865. The close proximity of the Colorado River made habitation and agriculture possible, despite the desert conditions. However, infrastructure in the remote area was poor; the Office of Indian Affairs, the federal agency that ran the reservation system, saw the planned camp as an opportunity to obtain roads, irrigation, and other necessities for economic development without having to fund them. The decision to take Poston's 71,000 acres was opposed by the Tribal Council on the grounds that they did not wish to participate in an injustice, but they were overruled by the Office of Indian Affairs and the army. One of the earliest to begin operations, it was the largest of the WRA camps in size and also in population, holding more inmates than any other "regular" camp; Tule Lake's population exceeded Poston's but only after it became the "segregation center." Building Poston was a massive undertaking, involving the construction not only of hundreds of buildings but also new irrigation canals and roads, in a desert area so remote that guard towers were considered unnecessary. Poston was the only facility under joint WRA and OIA administration, a status which changed in 1943 when the WRA took over sole control. [2]

Poston's inmates came largely from farming areas of Central and Southern California. Unusually, roughly two thirds of the inmates came directly to Poston from their homes, the remainder coming through various assembly centers, among them Salinas , Santa Anita , and Pinedale , as well as the Mayer Assembly Center in Arizona. This had two major consequences. First, Poston did not have the opportunity to benefit from experiences gained with running the assembly centers, and so especially in the earliest days, conditions were sometimes chaotic as inmates and administrators alike tried to figure out how things would work. Second, the qualified "improvement" in conditions from the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA)-run horse stalls and fairgrounds of the assembly centers to the more permanent WRA camps was not experienced by most at Poston, either in terms of conditions or housing; in fact, the use of materials unsuited to the desert meant that repairs were necessary even as, and in some cases before, inmates moved in. As with Manzanar, the other camp where large numbers were sent directly from their homes, volunteer early arrivals had greater opportunities than those who came later, and since most positions were assigned by the administration, this gave rise to a perception that some early arrivals were more aligned with the administration than with their fellow inmates. [3]

Upon completion, Poston consisted of three "units" separated from each other by approximately three miles, on a roughly northeast-southwest line. The inmates generally referred to them as "camps" rather than "units" and nicknamed them "Roasten," "Toasten" and "Dustin." A single fence surrounded the entire facility. Camp I, the northernmost, the first constructed, and the gateway to the other two, was roughly twice as large as Camps II and III. It contained the administrative headquarters, the hospital, and other centralized support facilities for the entire facility, as well as staff housing. A separate area outside the Camp I fence contained the army guards' barracks and additional staff accommodations. The site was large enough that even the farm areas were within the outer perimeter fence. At its peak population of 17,814, Poston was the third largest "city" in Arizona. [4]

Administration and Camp Life

John Collier, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, advocated self-government and supported the maintenance of traditional cultures, including a long-term connection to the land, as positive factors in community-building. He also believed in applying the social sciences to human issues and problems, and so he recruited Dr. Alexander Leighton, psychiatrist and a member of the Navy Reserve Medical Corps. Leighton would later produce The Governing of Men: General Principles and Recommendations Based on Experience at a Japanese Relocation Camp from his experiences at Poston. [5] Poston was unique in having multiple studies taking place simultaneously. Leighton created what he dubbed the Bureau of Sociological Research , the WRA assigned social scientists as part of their community analysis section, and it was also a site for the University of California's Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study . [6]

Within the camp, inmates did most of the labor needed to support the existence of the thousands within. Poston's inmates grew a wide variety of crops in addition to raising chickens and hogs; flowers were also tried, along with an unsuccessful attempt to raise guayule plants for their rubber, which was in short supply during the war. Japanese American workers were instrumental in making the area more livable, and although the majority of the basic infrastructure was built by the government, the inmates played a pivotal role in clearing, preparing, and irrigating the land. Land use and permanence proved to be a point of friction, as Commissioner Collier, head of the OIA, gave a speech urging inmates to think in terms of years, including long-term agricultural development, which was followed days later by an address by Myer , the WRA head, who laid out the WRA's intention to see the camp as transient and temporary. [7]

Beyond agriculture-related development, schools, auditoriums, and other public works were also built, in some cases of adobe, which could be made from materials at hand. In general, many tried to make the best of a difficult situation. Inmates worked to create a better situation for themselves through such strategies as building furniture for their compartments and making food, such as tofu, that was part of the accustomed diet for many. Creating parks, going fishing in the canals, and renting horses from Native Americans were other activities they took up on their own behalf. [8] Inmates also engaged in "home front" labor, such as making camouflage nets under contract, and the previously mentioned attempt at cultivating guayule. A number of Poston's inmates left the camp to work sugar beets, cotton and other seasonal agricultural products for which labor was in short supply due to the war. Many others departed for employment or education on a more permanent basis when cleared for "indefinite leave;" hundreds of young men and a few young women left for service in the armed forces.

Tensions and Resistance

Within Poston, inmates did not always simply accept the situations they found themselves in. When wage scales were announced shortly after Poston began operations, the incarcerated voiced disapproval over pay, the amount of work expected, and classification of jobs almost immediately, including an August strike of adobe workers. [9] When the administration announced that only the citizen Nisei would be allowed to serve on the elected " Temporary Community Councils ," inmates formed an unsanctioned "Issei Advisory Board" that represented that important group. During the first year of operations, delays in pay, in clothing allowances and with heating and insulation as colder weather came on, together with the overall injustice of the situation only exacerbated tensions.

One manifestation of these tensions were attacks on individuals suspected of being administration informers. In November 1942, an alleged informer in Camp I was beaten and seriously injured. The administration responded by holding two Kibei men without charges, pending an FBI investigation. Fearing that the two would not be given a fair trial, demonstrations were held, and after talks broke down, both the Temporary Community Council and the Issei Advisory Board of Camp I resigned, and a new representative body was elected with both Issei and Nisei leaders. A general strike for Camp I was called, with only necessary services provided for the duration. [10] Camps II and III were not involved. The roughly week long strike ended when the administration agreed to release both prisoners to the camp, with the stipulations that the beatings of informers would cease and that the inmates would work cooperatively with the administration. [11] Following the strike, inmates, notably Issei, played a larger role in determining the conditions under which they lived and no other general strikes occurred.

Poston was also the camp with the largest number of draft resisters , at 107 proportionately roughly equal to the numbers at Heart Mountain . While the Poston draft resisters were not as organized as those at Heart Mountain, similar public bulletins were printed and discussed. These actions attracted considerable support, including raising over $3,000 for a defense fund after one leader's arrest. [12]

A number of prominent individuals were incarcerated at Poston, including wartime JACL President Saburo Kido , sculptor Isamu Noguchi , writers Hisaye Yamamoto and Wakako Yamauchi , researchers Toshio Yatsushiro , Richard S. Nishimoto and Tamie Tsuchiyama , veteran/activists Rudy Tokiwa (WWII) and Vincent Okamoto (Vietnam) and George Fujii, wartime draft protester and one of the two men whose detention sparked the Poston Strike. Notable staff included William Wade Head, Project Director, Alexander Leighton, Bureau of Sociological Research, and Miles Carey and Arthur Harris, Directors of Education, all of whom were seen by many as sympathetic to Japanese Americans.

Aftermath and Remembrance

After the WRA closed Poston in 1945, the buildings, roads, canals and other improvements that resulted from the camp's operations were transferred to Native Americans. The irrigation system for Poston had been built at an estimated cost of more than $670,000, and its main canal was nearly seventeen miles long. Roads and bridges also had been constructed at an estimated expense of more than $900,000, including the main road from Parker to Camp III, which was more than twenty-one miles long. [13]

Today, although many of the original buildings are longer used and have either been demolished or fallen into disrepair, the story of Poston continues. The Poston Memorial Monument was built in 1992, with key support from the Colorado River Indian Tribes, upon whose land the memorial stands. Another legacy of this experience has been the widespread cultural production of different materials about the Poston experience. In History and Memory , Rea Tajiri traces her family's relationship to Poston, including the way many Japanese Americans chose not to discuss the camps after the end of the war. The film documents Tajiri's own reclamation of this piece of her family history and movingly shows the journey to the site of the camp, accompanied by a narrative from family members recounting their memories. [14] More recently, Passing Poston narrates the stories of four former inmates who are attempting to come to terms with their incarceration. [15] In 1997, the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles opened an exhibition entitled, "Dear Miss Breed: Letters from Camp," which is available at http://www.janm.org/exhibits/breed/title.htm . It features some of the museum's more than 250 pieces of correspondence sent by young Japanese Americans to Clara Breed , a San Diego children's librarian from 1929 to 1945. When Japanese Americans from the area left for the camps, she gave them prepaid postcards at the train station so that they could write to her about their experiences.

For More Information

Arizona Historical Society Library and Archives, Tempe, A Celebration of the Human Spirit - Japanese-American Relocation Camps in Arizona . https://azmemory.azlibrary.gov/nodes/view/244184 [Online collection of materials related to both Poston and Gila River.]

Bailey, Paul. City in the Sun: The Japanese Concentration Camp at Poston, Arizona . Los Angeles: Westernlore Press, 1971. [A general work on Poston.]

Estes, Matthew T., and Donald H. Estes. "Hot Enough to Melt Iron: The San Diego Nikkei Experience, 1942-1946." Journal of San Diego History 42.3 (1996): 126-73. https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1996/july/index-htm-64/ . [Article covering the experiences of those sent to Poston from San Diego.]

Fujita-Rony, Thomas Y. "Arizona and Japanese American History: The World War II Colorado River Relocation Center," Journal of the Southwest , 47:2 (2005): 209-232. [Article on the building of Poston, contextualizing it in region's history.]

Leighton, Alexander H. The Governing of Men: General Principles and Recommendations Based on Experience at a Japanese Relocation Camp . Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1946. [A general work about Poston and the strike, written during World War II by a generally sympathetic staff member.]

Nishimoto, Richard S. Inside an American Concentration Camp: Japanese American Resistance at Poston, Arizona . Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1995. [Four documents written at the time by Issei Richard S. Nishimoto, who was a camp leader as well as a researcher at Poston, along with contextual essays by editor Lane Hirabayashi.]

Poston Community Alliance, Inc. http://postoncamp.blogspot.com . [The most active group with regard to Poston, they maintain multiple topical websites with much information, and have coordinated reunions for former inmates.]

Tajiri, Vincent, ed. Through Innocent Eyes: Writings and Art from the Japanese American Internment by Poston I Schoolchildren . Los Angeles: Keiro Services Press and the Generation Fund, 1990. [First-hand accounts and artwork by children at Poston.]

Footnotes

- ↑ Jeffery F. Burton, Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord, and Richard B. Lord, Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002), 215.

- ↑ Burton, et al, 215-219.

- ↑ Commission on the Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997), 176-179.

- ↑ Burton, et al, 215-219.

- ↑ Alexander H. Leighton, The Governing of Men: General Principles and Recommendations Based on Experience at a Japanese Relocation Camp (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1945), 373.

- ↑ Richard S. Nishimoto, Inside an American Concentration Camp: Japanese American Resistance at Poston, Arizona (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1995), xxiii-xxxvii.

- ↑ Dillon S. Myer, Uprooted Americans (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1971), 61-62.

- ↑ Conrad M. Arensberg, "Report on a Developing Community: Poston, Arizona," National Archives, Record Group 210, Records of the War Relocation Authority, Entry 48 (Subject-Classified General Files), Box 124, Folder "Record Studies."

- ↑ Leighton, 86 and 106-107.

- ↑ Dorothy Swaine Thomas and Richard Nishimoto with contributions by Rosalie A. Hankey, James M. Sakoda, Morton Grodzins, and Frank Miyamoto, The Spoilage (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1946), 46.

- ↑ Leighton, 203-210.

- ↑ Eric L. Muller, "A Penny for their Thoughts: Draft Resistance at the Poston Relocation Center," Law and Contemporary Problems Vol 68, Winter 2004: 123-124; 144-145.

- ↑ "Appraisal Data Vol. II," National Archives Pacific Region (Laguna Niguel), Record Group 270, Records of the War Assets Administration, Box 9, Folder "Colorado River Relocation, Poston, AZ, Appraisal Data Vol. II."

- ↑ Rea Tajiri, History and Memory: For Akiko and Takashige , (Chicago: Video Data Bank, 1991).

- ↑ Joe Fox and James Nubile, Passing Poston: An American Story , (New Video, 2008).

Last updated Feb. 1, 2024, 10:25 p.m..

Media

Media