Poston Chronicle (newspaper)

| Publication Name | Poston Chronicle |

|---|---|

| Camp | Poston (Colorado River) |

| Start of Publication | December 22, 1942 |

| End of Publication | October 23, 1945 |

| Predecessor | Poston Information Bulletin & Official Daily Press Bulletin |

| Mode of Production | mimeographed |

| Staff Members | Unlike other WRA camp newspapers, the Poston Chronicle did not run a regular paper masthead listing staff, and most articles did not include bylines. Editors over the duration of the paper included Kaz Oka, Isao Fukuba, Susumu Matsumoto, Lily Maeno, and Bob Hiratsuka. |

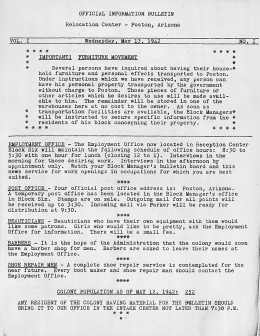

The Poston Chronicle (December 22, 1942–October 23, 1945) was the main newspaper of the Poston , Arizona, concentration camp. It was preceded first by the Poston Information Bulletin (May 13, 1942–July 9, 1942), then by the Official Daily Press Bulletin (July 10, 1942–December 20, 1942).

Background and Staffing

The War Relocation Authority camp newspapers kept incarcerated Nikkei informed of a variety of information, including administrative announcements, orders, events, vital statistics, news from other camps, and other necessary information concerning daily life in the camps. (See Newspapers in camp .) Story coverage was comparable to what one might typically expect of a small town newspaper, with nearly identical coverage in all ten camps of social events, religious activities (both Buddhist and Christian), school activities and sports , crimes and accidents, in addition to regular posts concerning WRA rules and regulations. Nearly every paper included diagrams and maps of the camp layouts and geographical overviews to allow residents to get a bearing of their locations; payroll announcements, instructions on obtaining work leaves and classified ads for work opportunities; lost and found items; and some editorial column that was reflective of its Japanese American staff editor. Reporters and editors were classified as skilled and professional workers respectively and received monthly payments. The wage scale was set at $12 or $16 a month for assistants and reporters and $19 for top editors, although no labor was compulsory. All ten camps had both English and Japanese language newspapers. Despite its democratic appearance, the camp newspapers in reality were hardly a "free" press. All newspapers were subject to some sort of editorial interference, in some cases even overt censorship, and camp authority retained the power to "supervise" newspapers and even to suspend them in the event that they were judged to have disregarded certain responsibilities enumerated in WRA policy. [1]

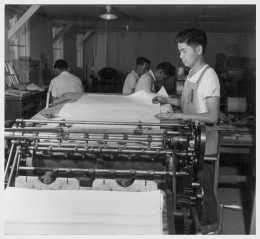

The Poston Chronicle began as the Official Daily Press Bulletin in May 1942, and was staffed by a five-man editorial board that managed the paper. Initially, the Press Bulletin published every day except for Mondays and sold at thirty cents a month. When the WRA took over administration of the camp from the Bureau of Indian Affairs in August 1943, the paper began to be distributed free to all families. It acquired the name of the Poston Chronicle in December 1942, and released its first issue under the Chronicle moniker on December 22, 1942. A handset printed edition on Sundays first appeared from April 18 to July 4, 1943. For most of its duration, the Chronicle was a daily except for Mondays; in the Fall 1943 it was released three times a week, then twice weekly, and finally as the center closing drew near, it only published weekly. All iterations of the newspaper were mimeographed except for the limited weekly printed issues that ran in the Spring/Summer of 1943.

Notable writers and editors who worked on the Poston Chronicle staff include Hisaye Yamamoto , Susumi Matsumoto, Henry Mori, Harry Honda, Kenny Murase, Isao Fukuba, Kaz Oka, Yoshiye Takata, Margaret Hirashima, Bob Hiratsuka, and Edith Fukaye. The paper featured several ongoing columns including "Corn-icle Jotings" by Susie Yamashita, "Small Talk" by Hisaye Yamamoto, and "Voice of an Issei" by Kuni Takahashi. The Poston Chronicle dedicated designated pages of the paper to all three separate camps: Poston I, II and III, with occasional pages reserved for student voices, in addition to sports coverage and the Japanese edition.

Coverage Highlights

In addition to the normal flow of community life covered in all other camp papers, the Chronicle also highlighted a number of issues of particular importance at Poston. Beginning in May 1942, it began to put out calls for inmates to serve as sugar beet workers to assist farmers outside of the camps. It reported on the steady stream of inmates leaving for such work, focusing on predominantly positive experiences reported by returning laborers. Classified advertisements for work both inside and outside camp were also a regular feature. For instance, such ads highlighted a Poston I factory that produced camouflage nets, ship models used as training aids for the navy, and an adobe brick plant that operated from Fall 1942 to May 1943. By Fall 1943, job announcements for work outside the camp were commonplace, including calls for domestic workers, chick sexers, pressmen, bakers, drivers, plumbers, dentists, and sharecrop farmers. The Chronicle reported on inmate dissatisfaction with the food and on Poston's expansive farming program and on a tofu factory that later augmented the diet. It also reported on conflicts between Issei and Nisei leaders.

Although there were a rash of night attacks in the fall of 1942 that are not mentioned in the newspaper, the most prominent incident that hit the Poston Chronicle pages was the so-called Poston Strike on November 14, 1942, when an attack on a man widely perceived as an informer resulted in the arrest of two popular inmates on the charge of assault with a deadly weapon. This incident culminated into a mass strike in Poston I, with a work walkout affecting some 6,500 inmates, although martial law was ultimately not imposed. Between November 14-24, 1942, the Chronicle did not mention the assault or mass strike at all. A terse article lauding the cooperation of "Administration as well as hundreds of fine loyal American-born Japanese" culled from a statement issued by Poston Project Director Wade Head appeared on November 24th, assuring readers both inside camp and to outside press that "the disturbances which had existed at the Colorado River War Relocation Project at Poston since Wednesday, November 18, have ended." A related article that day announced the formation of the Poston II Community Congress "to cope with and mediate emergency situations with camp administration," and displayed pro-administration leanings. According to the paper, an overwhelming majority of Poston II residents were against the strike. However, the Chronicle also reported that a minority element led by a former block manager (who resigned in protest) attempted to call a general sympathy strike in Unit II, asking for the complete and unconditional release of the men arrested in suspicion of the fatal assault. Most of the follow-up reports on the "Poston Incident" over the following days focused on negotiations over the suspects and reminded residents that contrary to rumor, martial law had not been imposed upon the camp. In January 31, 1943, the Chronicle reported that National Japanese American Citizens League President Saburo Kido was attacked for the second time. Eight inmates of Poston II were arrested and charged; five were later sentenced to a term of one to four years in the Arizona State penitentiary in Yuma. Reports of petty thefts of lumber and other building supplies, as well as chronic problems with gambling also continued throughout the camp's history.

Other news of interest reported in the Poston Chronicle included the permanent residency of Japanese-speaking Father Clement from Maryknoll Catholic Church in Los Angeles, (he served both Poston and Gila camps throughout the duration of the war), and the short-term residency of New York sculptor Isamu Noguchi , who engaged inmates in folk art and handicrafts fashioned from indigenous ironwood, petrified wood, and mesquite. Like many of the WRA camps, such arts and crafts classes helped fill monotonous hours of camp life.

At the end of 1944 the exclusion orders were lifted and the inmates were finally allowed to go home to the West Coast starting in 1945. The final issue of the Poston Chronicle was released on October 23, 1945, in Japanese and English, and included "A Happy Ending" editorial, describing the role of the Chronicle in unfolding the story of Poston page by page, along with closures of mess halls, storage announcements, and posthumous awards for recently deceased Nisei soldiers. Poston II and III both closed on September 29, 1945, and Poston I closed on November 28, 1945.

Footnotes

- ↑ Takeya Mizuno, "The Creation of the 'Free Press' in Japanese American Camps" Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 78.3 (2001), 514.

Last updated Feb. 1, 2024, 10:27 p.m..

Media

Media