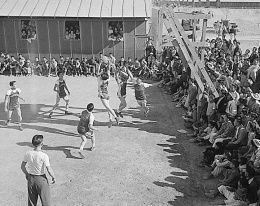

Sports and recreation in camp

During Japanese American incarceration (1942-1946), sports served as an escape from the monotony of prison life. In many instances sports functioned as a release valve for the social, economic, psychological, and political pressures created by incarceration based on ethnicity and ancestry. Sports were one link to normalcy for Japanese Americans after being forcibly removed from their West Coast communities. Some Nikkei played for the love of the game while others aimed to prove their value in society as well as in sports. Still others used sports as a way to resist government policies. Each of the ten permanent War Relocation Authority (WRA) Centers had a recreation department where Nikkei men and women worked with WRA officials to organize sports programs within the camps, many of which reflected the prewar bicultural experience of Nikkei communities.

From the time the Nikkei first settled on the West Coast, sports programs were an integral part of the community. For example in 1903, Chiura Obata created the first organized Issei baseball team, the Fuji Athletic Club (FAC), based in San Francisco. Concurrently, the Wapato Nippon Baseball Club formed in Wapato, Washington. In 1904 the KDC, (Kanagawa Doshi Club) formed near the San Francisco area. Finally, in 1908, the Issei of Seattle formed two teams who competed against white ballclubs.

With the expansion of competitive programs in the concentration camps, Nikkei used their previous knowledge to develop leagues in popular American sports like baseball, softball, football, basketball, boxing, volleyball, tennis, badminton, golf, and even marathons alongside traditional Japanese sports such as karate, sumo , and judo. They designed, built and enlarged fields and recreation centers to meet the diverse needs of inmates across multiple generations and genders. [1]

Assembly Centers

Immediately following issuance of Executive Order 9066 , but prior to the creation of the ten permanent concentration camps, seventeen hastily built " assembly centers " located throughout the West Coast were established under the auspices of the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA). Even though most assembly centers only operated for a period of six months, Japanese Americans instituted numerous sports programs and sports became a focal point of social activity.

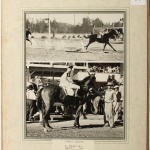

As indicated by the prominent and detailed coverage by assembly center and WRA camp newspapers , baseball and softball were the main sports for multiple generations of incarcerated men, women and the WCCA officials. Of the 7,816 inmates in Tanforan center, 1,170 played softball and baseball on 117 teams in seventeen leagues. In the Tanforan and Puyallup centers, incarcerees built nine-hole par three golf courses while those at the Santa Anita center constructed a driving range. Japanese Americans brought a majority of sports equipment in these camps, but many also used gear purchased through mail-order catalogs or provided by the WCCA. [2]

Baseball in the Camps

When Nikkei inmates transferred to the ten WRA centers, they brought their sports programs along with them. Baseball and softball remained the premier sports. According to Kerry Yo Nakagawa, despite obstacles unique to each camp, inmates designed and built baseball diamonds mainly during 1942, the first year in the camps. Famed "Dean of the Diamond," Kenichi Zenimura , with volunteers from throughout the Gila River center struggled to clear away the ubiquitous sagebrush and then faced the challenge of developing methods to reduce dust on the arid fields of Arizona. In an interview with Nakagawa, actor and former Gila River incarceree Pat Morita remembers "watching a little old brown guy watering down the infield with this huge hose. He used to have his kids dragging the infield and throwing out all the rocks...They worked like mules." [3] Similar backbreaking work went into baseball fields in Manzanar and Rohwer , while at the Jerome center, incarcerees removed tree stumps with dynamite provided by WRA officials. [4]

Beginning in 1943, incarceration camps hosted many interracial baseball games behind barbed wire. Idaho incarcerees even traveled outside of the center to the state tournament. As early as June 1943, the camp guards of Rohwer participated in softball games against the Nikkei inmates with the military police team led by Stg. Burke, a former semi-pro player, defeating the Japanese American Royal Dukes by a tally of 7-1. From July 25 to 31, 1943, sixteen Nisei players from Hunt/Minidoka incarceration camp made a 150-mile trip to the Fifth Annual Idaho State Semi-Professional Tournament at Idaho Falls. In the quarterfinal match, the Nikkei prisoner team played the Hunt Military Police Force, guards from the Minidoka camp, winning by a tally of 14-1. In May and July 1943, Jiggs Yamada and Ship Tamai of Tule Lake put together a game against the Klamath Fall Pelicans and another battling a white semi-pro All Star team from the Oregon League. The Tulean All-Stars won both affairs against the "invading" Caucasian teams by a score of 16-0 and 16-8 in front of nearly 5,000 Nikkei fans. No one doubted the talent of Japanese American players. [5]

One person who took great interest in Japanese American baseball players was Branch Rickey, owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers. In an open letter to all of the incarceration centers, Rickey stated of the Nisei baseball players: "The fact that these boys are American boys is good enough for the Brooklyn Club." As part of a radical plan he invited Nisei to participate in open tryouts for the team. In September 1943, three Nisei—pitchers Roy Sayeguchi and Henry Honda, and third basemen Ichi Hashimoto—attended the tryouts in front of scout George Sisler in Ogden, Utah. None made the team. [6]

The 1944 baseball season reflected the loosening of restrictions on Nikkei inmates deemed "loyal" to the U.S. Under the leadership of Zenimura, a series of inter-camp games took place in the summer and fall. The first series took place in June 1944 featuring an All Star team from Poston (Arizona) that travelled 200 miles to Gila River. Ironically, when prisoners donned baseball uniforms, the WRA provided these "enemy aliens" a bus to travel the long distances between centers to the inter-camp games unguarded—almost as though the baseball uniform conveyed greater acceptance as part of American culture. The six game series between the two camps ended with a series split. Members from the Poston group thanked the Gila River center before they left for their journey back to their camp. Gila River then welcomed the Amache players who trekked 900 miles from Colorado to play a series of baseball games. Gila River reciprocated and made the journey to Amache later in the season. Zenimura worked on a schedule for play and in the end, Gila River swept Amache in all eight games they played at each center. Most members of the All-Star team from Amache camp that participated in this series were bound for service in the United States Army's segregated all-Nikkei 442nd Regimental Combat Team . In September 1944, another inter-camp series took place between the Heart Mountain All-Star and the Gila River Internees. The Gila River team led by Zenimura made an 1,170-mile pilgrimage to Heart Mountain (Wyoming) to play thirteen games. [7]

Football

In many of the centers, the baseball season followed the major league calendar, beginning in the spring and ending in October. The Nikkei inmates then participated in winter sports such as football and basketball. In all ten centers, incarcerees played on the gridiron with teams consisting of six to eleven men. The intensity of games varied from camp to camp. Poston attempted to ban tackle football because there were too many injuries, yet Gila River Community Activities Supervisor Robert Yeaton enthusiastically supported such an organization. The camp's chief medical officer, Jack Crisp Sleath, stated it would be beneficial for young men to participate in sports of all types available for civilians outside the centers. Assistant Supervisor Harry Ota planned for the upcoming season with six and eleven man football teams and constructed two fields, one eighty yards long and the other the standard hundred yards. In Tule Lake, there was a senior (18 and over) and junior circuit for football with a clear series of rules established by October 23, 1942. [8]

Nisei also made great strides outside of the camps after transferring to colleges outside of the military zone. For instance, Jack Yoshihara, who played for Oregon State in 1941, was unable to participate in the Rose Bowl because of wartime travel restrictions, even though the game was played in Durham, North Carolina. (Oregon State won the game 20-16 over host Duke University.) Yoshihara and Jimi Yagi, formally of San Jose State, made the University of Utah football roster in 1943. Sam Kiguchi and Min Sano, formerly of UCLA and Berkeley respectively, also transferred in order to play collegiate football. Chester "Chet" Maeda was a two-sport star with the Colorado Aggies. Maeda was the team's halfback and won all conference honors in 1942 while also a member of the basketball team. In 1943, the Detroit Lions drafted him in the 18th round, and he eventually made his professional debut for the Chicago Cardinals in 1945. [9]

Basketball

Inmate "cagers" played basketball in recreation centers and on outside courts. Play varied according to camp policies. Sometimes, work on the outdoor courts was delayed because of weather and lack of materials as in the case of Minidoka, Idaho, in March 1943. In February 1943 the basketball season at the Heart Mountain center ranked thirty-five teams into three leagues. Later it held two "dream team" all-star game matches among incarcerees. Japanese American inmates also played against Caucasian teams in numerous camps. Louie Watanabe, a member of the Granada/Amache Center (Colorado) basketball team remembers playing local high schools. [10]

Concurrent with basketball in the centers and located about 150 miles away from the Topaz incarceration center, Wataru Misaka led the University of Utah to the 1944 NCAA title. Misaka, a 5'7" point guard born in Ogden, Utah, outside of the military zone, was never incarcerated during the war. In the postwar era he became the first professional non-Caucasian to play in the National Basketball Association. His career lasted three games. Eventually he was cut from the New York Knicks and became an engineer. [11]

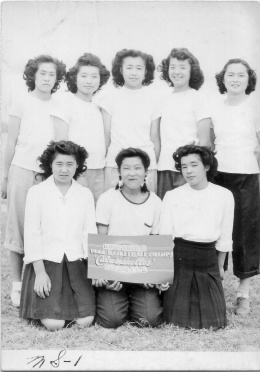

Women

Women played various sports in the centers. Yet, a majority of camp newspapers did not cover them with the same consistency and esteem as their male counterparts. Their participation in sports began at the assembly centers. Prior to segregation, Gila River, Rohwer, Manzanar, and Tule Lake provided the most coverage for "girl's sports." Throughout incarceration, softball, basketball, and volleyball were the three main sports for women in all of the centers. In some of the camps women organized and managed their own sports programs. Between April and June 1943, Tule Lake camp members formed the Girls' Athletic Association with Dot Keikoan serving as president. [12]

Almost all of the camps had a senior and junior (fifteen and younger) girls' league. Team names like the Babes, Zepherettes, and Jinxes were popular in many of the centers. In November 1942, the Topaz Times (Utah) referred to a possible "conspiracy" during a battle of the sexes baseball game played in the center. In a match up between Issei men-over-50 and Nisei women's all-star team, the women led for six innings before the men "nosed out" a 9-8 victory. After the game the Nisei women called for a return game claiming the Issei team cheated with "three youngsters" less than 50 years of age. Much to the chagrin of the women, no rematch took place. Off the field, women also played an integral role in the men's sports. Many times women were the ones stitching the lettering onto men's uniforms and creatively converting potato sacks into baseball pants. [13]

Martial Arts

Often associated with Asian culture, martial arts were popular within the centers. Judo, arguably Japan's national pastime and still among the most popular sports in the world, had many adherents. Yoshitaro Sakai held the first tournament at the Santa Anita Assembly Center in July 1942 with over a hundred participants. Though the tournament only featured men, by August over forty women and girls had signed up for judo classes as well. Given inmate enthusiasm for the sport, inmates bought unfinished judo gis from the Pomona center to the Heart Mountain center in order to participate, completing the garments piecemeal. The popularity of the sport led to the creation of a 2,400 square foot facility in Manzanar with an estimated 400 to 600 participants daily under the direction of Seigoro Murakami and Shigeo Tashima. The Tule Lake center featured four different dojos, and Rohwer and Jerome had multiple intercamp battles. [14]

As with other sports, judo competitions brought Caucasians from outside the centers together with the Japanese American inmates. Jack Sergel—better known by his stage name, John Halloran—a sergeant from the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) and a third dan, brought a group of judoists to participate in tournaments at Manzanar multiple times. The FBI forced Sergel to resign from the LAPD after an investigation into his affinity for judo and Japanese culture. [15]

Sumo was another popular Japanese sport in the camps. It too began in the assembly centers. According to the Tanforan Totalizer over 2,000 spectators came to the debut tournament in June 1942. Individuals built sumo pits and held tournaments in the spring, summer, and fall. The two camps in Arkansas, Rohwer and Jerome, had multiple inter-camp sumo and judo tournaments. While Rohwer won judo, the Jerome camp took home the sumo title in July 1943. In September 1943, Jerome held a special tournament for those resisters bound for Tule Lake against " yes-yes " sumoists. The Heart Mountain center held a sumo tournament as part of the Bon Odori Festival while the Tule Lake camp featured it as part of the Independence Day celebration in 1943. [16]

Other Sports

Focusing as they did on baseball, the camp newspapers often failed to cover other popular sports available to incarcerees at the ten centers including archery (Topaz), fencing (Gila River), running, and track and field sports. Minidoka, Topaz, and Tule Lake all attempted to host marathon races, but with uneven results. Minidoka planned for a 1942 Halloween run but shortened the length of the race in hopes of gathering more participants. The 1943 New Year's Day marathon at Topaz also lacked runners; in fact only two— Harry Sakata and Dan Ota—competed in this event. Tule Lake held a team marathon up and down Castle Rock, a bluff near the camp, in April 1943. Much more popular were the track and field events that took place in most of the centers. These were predominantly at the junior level by high school students such as at Heart Mountain, which held inter-block track and field meets on Independence Day and August 18, 1945. [17]

Sporting Resistance at Tule Lake

After the so-called loyalty questionnaire and the designation of Tule Lake as a segregation center, even sports became a contested arena given the rising tensions within the center. When inmates at post-segregation Tule Lake claimed the WRA failed to allot adequate funds for their sports activities, incarcerees worked directly with the California Athletic Department (CAD), bypassing the recreational division of the WRA. This meant that the inmates and the CAD oversaw, financed, and operated two "A" baseball leagues largely independent of Tule Lake officials. [18]

Further, while the camp director Raymond Best saw the opening of the 1944 baseball season as an All-American affair, Nikkei inmates sought to promote the Japanese-ness of the game. Culture and language became a platform for returning to their roots of yakyu , or fieldball. Tule Lake's Major Hardball League (MHL) had two divisions, Taiheiyo (Pacific) and Taiseiyo (Atlantic). Baseball teams also initiated the season with the traditional Japanese entrance ceremony, nyujorhiki , the ceremonial first pitch shikyushiki , and utilized Japanese names for their teams. Over half of the center's population was present for opening day, which came on the heels of ceremonies celebrating the birth of the emperor in Japan. An ironic scene ensued when Best threw out the first pitch to his catcher Lorne Huycke, supervisor of community activities, as 84-year-old inmate Minokichi Fukui played the role of the umpire judging Best's pitch—an opportunity to judge their oppressors, if only in a ceremony. [19]

Sport is often referred to as a bastion of equality and democracy. The need for such a bulwark was vital to the more than one hundred and ten thousand Issei and Nisei forcibly relocated from the West Coast to ten WRA camps where they lived behind barbed wire fences and armed guard towers in interior of the United States. Sports reflected the bicultural values and experiences of Japanese Americans in the WRA centers during the time of incarceration. Over sixty percent were native born American citizens and some had fought for the United States in World War I. The embrace of typically "American" sports by those incarcerated because of their Japanese ancestry speaks to the duality and complexity of the Japanese American experience. Sports also offered a medium for communication and interaction between and among the multigenerational, gendered, and varied cultural experiences of the incarcerees as well as with the Caucasian guards and officials of the WRA. Sports like judo and sumo also provided inmates the opportunity to preserve and pass along elements of Japanese culture. The talent, perseverance, and performance of athletes—whether measured in between the chalk lines, on the gridiron, or hardwood court—represented the spirit of the game and "American values."

For More Information

Diamonds in the Rough: Zeni and the Legacy of Japanese-American Baseball . DVD. Chip Taylor Communications, 1999

Elias, Robert. Baseball and the American Dream: Race, Class, Gender, and the National Pastime . Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2001.

---. The Empire Strikes Out: How Baseball Sold U.S. Foreign Policy and Promoted the American Way Abroad . New York: The New Press, 2010.

Fitts, Robert K. Remembering Japanese Baseball: An Oral History of the Game . 1st ed. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005.

Franks, Joel S. Asian Pacific Americans and Baseball: A History . Lincoln: McFarland, 2008.

---. Crossing Sidelines, Crossing Cultures: Sport and Asian Pacific American Cultural Citizenship . Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2009.

Guides, Minute Help. Sumo: A History . CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2012.

Guthrie-Shimizu, Sayuri. Transpacific Field of Dreams: How Baseball Linked the United States and Japan in Peace and War . Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2012.

Matsumoto, David, and Michel Brousse. Judo in the United States: A Century of Dedication . Berkeley, Calif.; Enfield: North Atlantic, 2005.

Nakagawa, Kerry Yo. Through a Diamond: 100 Years of Japanese American Baseball . 1st ed. San Francisco: Rudi Pub, 2001.

---. "Gila River Pilgrimage," 2008. https://niseibaseball.com/

Rafferty-Osaki, Terumi. "Battered but not Broken: Baseball and Masculinity at Tule Lake 1942-1946." In The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 2013-2014 . Ed. William M. Simons. Lincoln: McFarland Press, Forthcoming.

Regalado, Samuel. Nikkei Baseball: Japanese American Players From Immigration and Internment to the Major Leagues . Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

---. "Sports and Community in California’s Japanese American Yamato Colony 1930-1945." Journal of Sports History 19 (Summer 1992): 130–43, 199.

Transcending: The Wat Misaka Story . Directed by Bruce Alan Johnson and Christine Toy Johnson. DVD. ReImagined World Entertainment, 2010.

Whiting, Robert. The Meaning of Ichiro: The New Wave form Japan and the Transformation of Our National Pastime . New York: Warner Books, 2004.

Footnotes

- ↑ Kerry Yo Nakagawa, Through a Diamond: 100 Years of Japanese American Baseball (San Francisco: Rudi Publishing Co., 2001), 4-33. The KDC, ( Kanagawa-ken —their native prefecture, Doshi —"together" or "group" Club represented Nikkei ties to Japan, whose link to baseball begins with Rev. Okumura born in Kochi on the island of Shikoku. According to Nakagawa, he learned the game in 1873 from his American schoolteacher. Five years after immigrating to Honolulu, Reverend Takie Okumura established the first Japanese-American baseball squad, the Excelsiors in 1899. In Hawai'i the Japanese experienced racism and discrimination on the plantations, but they also built communities based on racial solidarity, coalitions with other ethnic groups, and formed an "American identity" with baseball, which also served to heal intra-prefecture tensions carried over from Japan. In the 1920s, Rev. Chimpei Goto organized baseball teams in Oahu specifically to aid immigrants from Okinawa, an island prefecture located some 900 miles south of the main Japanese islands, who were seen as "impure" because most were not pious Buddhists: They faced discrimination by whites and by other Japanese. For more information on baseball in Japan and Hawaii see: Yukiko Kimura, Issei: Japanese Immigrants in Hawaii (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press: 1988), 80-82, 161; Terumi Rafferty-Osaki, "Asians and Baseball: The Breaking and Perpetuating of Stereotypes," in The Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 2007-2008 , ed. William M. Simons (Jefferson: McFarland Publishing Co, 2009), 1310146; and Theo Balcolm, "Japanese Baseball Began On My Family's Farm In Maine," National Public Radio, http://www.npr.org/blogs/parallels/2014/03/28/291421915/japanese-baseball-began-on-my-familys-farm-in-maine , March 28, 2014.

- ↑ There is a discrepancy in the number of participants. According to "Down the Home Stretch," Tanforan Totalizer , June 13, 1942, there were 1,670 player on 110 teams however the final camp newspaper "Down the Home Stretch," Tanforan Totalizer , September 12, 1942 claimed there were only 1,170 players; Kerry Yo Nakagawa, Through a Diamond ; "Divotmakers' Delight: Par 27," Tanforan Totalizer , August 1, 1942, 4. Louis Fiset, Camp Harmony: Seattle's Japanese Americans and the Puyallup Assembly Center (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 138; "Golf Driving Range Now Ready for Use. Beginners May Get Information," Santa Anita Pacemaker , August 5 and 8, 1942, 6.

- ↑ Nakagawa, Through a Diamond , 86.

- ↑ In Manzanar, teams gathered decomposed granite from the surrounding hills to help build the field. In Rohwer, baseball diamonds were "set amid thousands of acres of recovered swamplands." See: Nakagawa Through a Diamond, 77-78 and Robert Asahina, Just Americans: How Japanese Americans Won a War at Home and Abroad (New York: Gotham, 2006), 28.

- ↑ "Military Police Nine Lambasts Royal Dukes 7-1; Ken Hirata Homers," Rohwer Outpost , June 9, 1943. This was not the last time Japanese inmates challenged the MP at Rohwer. See also: "Rohwer All-Stars Play Military Police: Hurling Duel Expected," Rohwer Outpost , June 26, 1943; All-Stars Blanked by M.P.'s, Burke Hurls Two-Hitter," Rohwer Outpost , June 30, 1943; "MP's Smothered 13-2," Rohwer Outpost , August 4, 1943; "MP's to Play Rebels," Rohwer Outpost , March 18, 1944 and "Rebels Mangle MP'S," Rohwer Outpost , March 22, 1944. For information on the Minidoka baseball squad, see: "All Stars Enter Idaho State Semi-Pro Tournament," Minidoka Irrigator , July 17, 1943; "Merchants eliminate Hunt From Tourney with a 7-3 Win: All-Stars Place Fourth in a Field of Eight; Bombers win State Title," Minidoka Irrigator , August 7, 1943.See also "Hunt's Area Ball Teams Win Three Contests from Visitors," Minidoka Irrigator , September 16, 1944. Finally, for information Tule Lake see: Klamath Falls Elks Plays Local All-Stars on May 30," Tulean Dispatch , May 21, 1943. An interesting note, the Dispatch had the wrong team name for Klamath Falls in two papers, May 21 and on May 25, but by May 28, 1943. Additionally, the paper reported the wrong starting battery of Pitcher Virgel Haines and catcher Virgel Cross just two days before the game (Barnhill and Derrah were listed as the pitcher and catcher of record); "Hardball Practices For All Star Choices to Start, " Tulean Dispatch , May 25, 1943, 4; "Pelican Starts Revealed for Big Sunday Clash," Tulean Dispatch , May 28, 1943, 4; "All-Stars Drub Pelicans 16-0 in Hardball Opener," Tulean Dispatch , June 1, 1943, 4; "Outside Semipros to Play Local All-Stars," Tulean Dispatch , July 14, 1943, 4; Hideo Shinkatu, "Sportstraits," Tulean Dispatch , July 29,1943. "Local All Stars Dump Cal-Ore Team; Ward 3 Wins Again," Tulean Dispatch , July 19, 1943; "Big Dust Storm Hits Project Sun. Afternoon," Tulean Dispatch , July 19, 1943; and "Tule Lake All Stars Blas Cal-Ore Semi-Pros, 16-8," Tulean Dispatch , July 20, 1943.

- ↑ "Nisei Ballplayers, Attention!" Rohwer Outpost , July 24, 1943. See also: "Here and There," Topaz Times , July 29, 1943. The letter was originally sen to Mr. Ira Holland in the School Health and Physical Education Department. In it Rickey stated: Dear Mr. Holland, We will be most happy to have any boys that you might recommend in our baseball camps this summer if any of these boys have sufficient ability to play professional baseball, we will, of course, recommend them just as we would any other young man. The fact that these boys are American boys is good enough for the Brooklyn Club. Whether they are of Japanese, English, or of Polish ancestry makes no difference to us and I know that these boys would be treated with the greatest courtesy and respect. Unfortunately, I am afraid that the camps which we run this summer will not be too close to McGehee, Arkansas. Our nearest camp may be in Oklahoma somewhere around the latter part of August. We will hold camps in Des Moines, Iowa, Omaha, Neb., for these. There may also be a possibility that later in the summer we may conduct a camp at Little Rock, Ark. At any rate, if any of the boys are able to attend any of these camps we would be more than happy to have them. Very Truly yours, Branch Rickey Jr.

- ↑ "Poston Arrives, First Game is Saturday," Gila River Courier , June 28, 1944, 6. See also: " 'Arizona Yankees' Open Series Against 65," Gila River Courier , July 1, 1944, 6; "Poston III Nine In Canal Debut Tonight," Gila River Courier , July 4,1944, 6; "Canal-Poston Finale Scheduled Tonight," Gila River Courier , July 6, 1944, 6 and "Yankees Thanks to All," Gila River Courier , July 11, 1944, 6. "Amanche All-Star Series Here is Delayed," Gila River Courier , August 12, 1944, 6. "All-Stars Are Gila Bound," Granada Pioneer , August 16, 1944, 6. "All-Stars Swept Clean at Gila," Granada Pioneer , August 30, 1944, 6. See also: "Amache All-Star Series Here Confirmed," Gila River Courier , August 10, 1944, 6 and "Canal, Butte Sweep Weekend Series," Gila River Courier , August 22, 1944, 6. Key Kobayashi, "Player's Description of the Heart Mountain Series," Gila River Courier , September 9, 1944, 6; "Luck of Gila Junior All-Stars Hold as They Win," Gila River Courier , September 12, 1944, 6; and "Heart Mountain Nine Journey to Gila," Rohwer Outpost , September 8, 1943, 6.

- ↑ "Temporary Rules for Six Man Touch Football," Poston Chronicle , November 11, 1942, 2; Dr. Powell Recommends Curb on Unsupervised Sandlot Tackle Football. Suggests Working Out of Safer Conditions of Play, Supervision," Poston Chronicle , December 2, 1944, 1-2; Jack C. Sleath, Medical Officer, Gila River, Memorandum "Playing Tackle Football," to Leroy Bennett, Project Director, December 18, 1942 RG 210, Entry 48, Box 140, File: 540, Health in Gila River Relocation Center, NARA DC. "Sports Staff Sighting," Gila River Courier , September 12, 1942, 15; Gila Athletic Union to be Organized; Six-Eleven Men Football Voted by Athletes, Gila River Courier , September 30, 1942, 6; "Thirteen Teams Turn in Rosters," Gila River Courier , October 10, 1942, 7. "Touch Football to Start this Week" and "Touch Football Rules and Regulations Disclosed," Tulean Dispatch , October 21, 1942; "Foot ball Rules Completed," Tulean Dispatch , October 23, 1942. For other examples please see: "Boy Scout Six Man Grid Loop Opens Today, Heart Mountain Sentinel , October 24, 1942; "All-star Football Team Named," Heart Mountain Sentinel , January 1, 1943, 8; "Eight Man Football Rules," Manzanar Free Press , October 1, 1942; "Hunt Gridders Loosen Arms and Toes for Football Contest," Minidoka Irrigator , September 29, 1942, 4; "Hunt Grid Team Gets Invitation," Minidoka Irrigator , October 2, 1942, 5; "Football Meeting," Granada Pioneer , November 11, 1942, 4, and "Football," Topaz Times , October 21, 1942, 2.

- ↑ "Honorary Degree Recipient Jack Yoshihara Passes Away," Oregon State University Admissions Blog , http://oregonstate.edu/admissions/blog/2009/05/14/honorary-degree-recepient-jack-yoshihara-passes-away/#sthash.rgUmoCIn.dpbs , May 14, 2009; Manzanar Committee PR, "Recommended Reading: War And The Roses For Oregon State – Los Angeles Times," http://blog.manzanarcommittee.org/2008/11/23/recommended-reading-war-and-the-roses-for-oregon-state-los-angeles-times/#more-246 , November 23, 2008; J.D. Chandler, Hidden History of Portland, Oregon , (Portland: Book News Inc, 2013), 127-131; and Tsuruta, "Nisei Footballers," Granada Pioneer , September 22, 1943, 6.

- ↑ Hiromi Miyagawa, "Sports Review," Minidoka Irrigator , December 25, 1942, 24; "Outdoor Courts Planned for Each Athletic Field," Minidoka Irrigator , March 20, 1943, 7; "Work on Athletic Fields Progress," Minidoka Irrigator , March 27, 1943, 7, and "Athletic Fields Near Completion," Minidoka Irrigator , April 3, 1943. "35 Center Basketball Teams get Set for League Contests," Heart Mountain Sentinel , February 27, 1943; "Class B All-Star Cage Aggregation Revealed," Heart Mountain Sentinel , April 10, 1943; "Sentinel All-Star Five Dominated By Champions," Heart Mountain Sentinel , March 11, 1944, 7; "45 Candidates Turn Out for First Cage Practice," Heart Mountain Sentinel , November 18, 1944, 7, and "Cage Champions Place Three Men on Sentinel All-Star Team," Heart Mountain Sentinel , March 24, 1945, 7. Louie Watanabe interviewed by Tom Ikeda and Jill Shiraki, "Playing local high school basketball teams (Segment 34)," Densho Digital Repository, December 8, 2009.

- ↑ Jon Wertheim, "Decades before Lin, Misaka made History for Asian Americans," Sports Illustrated , http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/2012/writers/jon_wertheim/02/11/jeremy.lin.wataru.misaka/ , February 11, 2012. See also: George Vecsey, "Pioneering Knick Returns to Garden," New York Times , August 11, 2009 and Bill Chappell, "Pro Basketball's First Asian-American Player Looks At Lin, And Applauds," NPR , http://www.npr.org/blogs/thetwo-way/2012/02/15/146888834/pro-basketballs-first-asian-american-player-looks-at-lin-and-applauds , February 14, 2012.

- ↑ "Girls' Athletic Assn Formed by Rec Department," Tulean Dispatch , April 29, 1943, 4; "GAA Sets Meeting; Yell Leaders to Try Out," Tulean Dispatch , May 13, 1943, 4; "Girls' League Will Meet Saturday," Tulean Dispatch , June 3, 1943, 4, and "Girl's Officers Elected," Tulean Dispatch , June 8, 1943, 4.

- ↑ "Men beat Girls in Softball Game," Topaz Times , November 2, 1942, 2. The following are examples of articles in the camp papers and represent a very small sample size. Like their male counterparts, women of Jerome and Rohwer also had intercamp sports battles, "Jerome Girl's Team Whips Rohwer Nine," Rohwer Outpost , August 4, 1943, 7 and "Rohwer Girls' Team Rallies to Whip Jerome," Rohwer Outpost , August 18, 1943. Male sports writers were not kind to "girls" who played sports, an example of this is "Dust and Desert," Poston Chronicle , June 20, 1944, 4. Others, like Gila River and Granada made women's sports programs visible, see: "Second Week of Fem Volleyball," Gila River Courier , October 3, 1942 and "Sepoi Girls nip 8E 3-1," Granada Pioneer , April 17, 1943. For images of women and sports, see: "Within Sports Focus," The Minidoka Irrigator , April 21, 1945, 4 and "Great American Pastime," Manzanar Free Press , March 20, 1943, 13. Nakagawa, Through a Diamond , 78-79. In an interview with Hugo Nishimoto, internee and manager of the Placer-Hillman Squad, Tule Lake of 1943, Nakagawa notes, "Jerseys were ordered from Sears and Roebuck and one of the fellows stenciled in the name. The pants were potato sacks that came from the farm...bleached white." Nakagawa also states, Women sewed uniforms, sometimes using the canvas covered ticking from government issued mattresses and At Topaz, red lettering was stenciled in and made possible by using mattress ticking.

- ↑ "Open Fem Judo Classes," Santa Anita Pacemaker , July 4, 1942; "More than 100 Sign up for Judo Tourney," Santa Anita Pacemaker , July 22, 1942, 5; "Top Judomen Vie in Tourney Sunday," Santa Anita Pacemaker , July 25, 1942, 5, and "Girls Judo Class Schedule Change," Santa Anita Pacemaker , August 15, 1942. Unfinished Judo Garments to be Completed Here, Heart Mountain General Information Bulletin Series , September 15, 1942. Within Six weeks the popularity of the sport drew in over 150 participants with more men, women and children on the waitlist for gis, see: "150 Attend Judo Class," Heart Mountain Sentinel , October 24, 1942, 6. "Center Judo in Full Swing," Manzanar Free Press , August 5, 1942, 4; "Judo Captures Young Huskies; 400 Strong Turning Out Daily," Manzanar Free Press , August 24, 1942, 4; "Two Day Judo Tourney Brings Big Turnout," Manzanar Free Press , September 24, 1942, 4, "Judo Big Sport in Manzanar," Tulean Dispatch , May 5, 1943, 4. "Extensive Judo Program Mapped Out," Newell Star , May 18, 1944, 6. "Inter-Center Judo Match Planned," Rohwer Outpost , April 28, 1943, 5; "Rohwer Judo Team Meets Jerome Sunday. Sakai and Iriye Lead Locals, Rohwer Outpost , June 12, 1943, 6; "Rohwer Judo Team Ties Jerome in Tournament. Return Meet Scheduled Soon, Rohwer Outpost , June 16, 1943, 5; "Judo Tournament Successful. Jerome-Rohwer in Return Tourney, Rohwer Outpost , August 4, 1943, 8; "Denson, Rohwer Judoists Will Tangle Sunday. Top Men from Two Centers to Trade Grips in Block 22 Ring," Denson Tribune , June 11, 1943, 7, and "Local Judo Artists Outpoint Rohwer Grapplers," Denson Tribune , June 15, 1943, 7.

- ↑ "Reminiscing—Golf, Judo and Tennis," Manzanar Free Press , December 22, 1943, 7. See also: Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation, Volume 2 , edited by Thomas A. Green, Joseph R. Svinth, 532 and 595.

- ↑ "Sumo," Tanforan Totalizer , June 13, 1942, 8. For another example in the assembly centers, see: "Sumo Matches Staged," Puyallup Camp Harmony News-Letter , June 25, 1942, 2. "Sumo Stars to Hold Tournament Sunday: 18 Jerome Wrestlers in Action," Rohwer Outpost , June 5, 1943, 6; "2000 Sumo Fans See Rohwer Trim Jerome: Kiriu Cops Gold Trophy" Rohwer Outpost , June 9, 1943, 5; "Local Sumo Men Meet Jerome: Rohwer Seeks Second Win," Rohwer Outpost , July 10, 1943, 5; "Jerome Whips Local Sumoists. Rohwer Loses by 10-8 Score," Rohwer Outpost , July 14, 1943, 5; "Local Sumo Men Bow to Rohwer Grapplers," Denson Tribune , June 11, 1943, 7; Sumo Tourney Fetes Tule Bound Men: Farewell Event Slated for Sunday Night, Denson Tribune , September 3, 1943, 7. "Fourth Program Starts Today: Sumo, Ball Games, Talent Shows, Dances on 3 Day Schedule," Tulean Dispatch , July 3, 1943, 3; Eric Muller, Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II (Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2012) 7, 92, and 111. A small sample of additional articles: "Sumo Tournament to be Held Saturday," Heart Mountain Sentinel , September 1, 1943, 2; Sumo Tourney Set For This Saturday; Plans For Labor Day Program Being Discussed" Tulean Dispatch , August 6, 1943, 3; "Community Activities to Assist in Encouraging 'Sumo' Again on Block Activity Basis," Poston Chronicle, November 14, 1944, 2. See also: Joe Yasutake, "Activities in Crystal City internment camp: judo, sumo and baseball" (segment three) interviewed Alice Ito, Densho Digital Repository, Seattle, Washington, October 9, 2002.

- ↑ "Archery," Topaz Times , July 29, 1943, 5. "Fencing to Start Soon," Gila River Courier , December 9, 1942, 6. "Marathon Race Carded for Big Halloween Festival," Minidoka Irrigator , October 17, 1942, 2; "Gala Holiday Doings Listed," Minidoka Irrigator , October 28, 1942, 6; "Many Prizes Offered in Marathon Race," Topaz Times , December 28, 1942, 6; "Route Revised for Marathon; Prizes Offered," Minidoka Irrigator , October 31, 1942, 4; "News Briefs; Marathon," Topaz Times , January 5, 1943, 1; "Marathon Relay Contest Entry Deadline Extended," Tulean Dispatch , April 12, 1943, 3; "16 Teams Set For Marathon" Tulean Dispatch , April 17, 1943, 1; "Block 9 Relay Team Cops First Place in Marathon: Second Goes to Block 19," Tulean Dispatch , April 20, 1943, 4. Japanese inmates used the term "marathon," in a more liberal fashion as this course was a "grueling five miles up and down the Castle Rock." "Centerwide Track and Field Meet Slated Independence Day," Heart Mountain Sentinel , June 30, 1945, 7 and "Inter-block Track and Field Meet Scheduled," Heart Mountain Sentinel , July 28, 1945, 7. These two articles are a small sample as track and field was popular at all of the centers, but did not receive the same level of coverage.

- ↑ "Baseball 1944: Tule Lake Center," Newell Star , December 31, 1944.

- ↑ "Grand Ceremonies to Inaugurate Hardball Circuits on Saturday," Newell Star , April 27, 1944, 5. For the contrasting names of teams see: "Hardball Standings" Tulean Dispatch , August 26, 1943 and Industrial Standings, Tulean Dispatch , August 27, 1943; and "Baseball 1944: at Tule Lake Center," Newell Star , December 31, 1944. "Tulean Hardball Season Opens; Nippons Dump Manzanar Nine 12-6," Newell Star , May 4, 1944, 5.

Last updated Jan. 15, 2024, 4:54 a.m..

Media

Media