Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee

The Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee was a membership organization of draft-age Nisei men at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center that advocated for a restoration of Nisei civil rights as a precondition for compliance with the military draft and counseled noncompliance with the draft in order to create a test case of the lawfulness of conscripting the incarcerated Nisei.

Origins

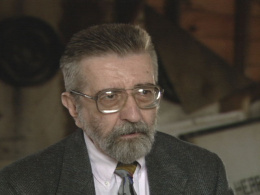

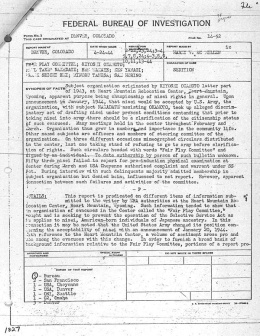

The organization formed around the charismatic figure of Kiyoshi Okamoto, a perennial critic of the policies of the War Relocation Authority and its administrators at Heart Mountain. In February of 1943, when a military team came to Heart Mountain to oversee the administration of the government's ill-fated loyalty questionnaires , Okamoto had participated in an ad hoc "Congress of American Citizens" that unsuccessfully demanded a clarification of Nisei rights as a condition for filling out the questionnaires. Okamoto continued his public criticism of government policies throughout 1943, at some point coming to refer to himself as a "Fair Play Committee of One."

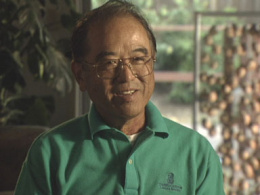

At the end of 1943, a small group of other Nisei men at Heart Mountain including Frank Emi and Paul Nakadate approached Okamoto to hear his views about the illegality of the incarceration of Japanese Americans. They began meeting regularly to share grievances, discuss strategies for restoring Japanese Americans' rights, and consider Okamoto's theories about constitutional law.

These early meetings were informal, but when the government announced in late January of 1944 that the imprisoned Nisei would be eligible for conscription into the U.S. Army under the Selective Service Act of 1940, this fledgling group found its cause. On February 8, 1944, just a few days after the first draft notices arrived in the mail at Heart Mountain, the group—now calling itself the "Fair Play Committee"—convened a public meeting in a mess hall. Sixty young men showed up and heard speeches from Okamoto and Nakadate decrying the unfairness and illegality of applying the draft to people incarcerated in the WRA camps and of conscripting the Nisei into a segregated army unit.

The Fair Play Committee quickly established criteria for membership and a $2 membership fee. In order to belong to the organization, a person needed to be a U.S. citizen who was loyal to the United States and willing to serve in the U.S. Army if his legal rights were first restored. Both of these points were crucial to the organization's sense of its identity and to its message: the group did not wish to be seen as disloyal to the United States or as pacifist.

Throughout the months of February and March of 1944, the Fair Play Committee hosted evening meetings in mess halls around the camp. Attendance at the meetings swelled as more and more young men received orders to report for pre-induction physical examinations and confronted the question of whether or not to comply with the law.

Advocating Draft Resistance

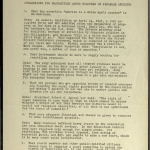

Also during this time, the leadership of the Fair Play Committee drafted, copied, and posted around the camp several broadsides that articulated the group's developing position about the draft. At first, they pitched their message at a fairly abstract level, presenting broad arguments rather than plans of action. They criticized the racial discrimination in the creation of an all-Nisei army regiment as well as the mass removal and imprisonment of all Nisei, and they asked for what they termed a "clarification" of the rights of the Nisei. The group appeared to be trying to avoid an outright call for noncompliance with the draft, a message that the government would likely see as unlawful.

However, in a March 4 poster, their message took a different, fateful direction: the group announced that its membership would "refuse to go to the physical examination or to the induction if or when we are called in order to contest the issue." And this is just what began to happen. Starting on March 6, 1944, young men began refusing to report for their physical examinations—first two, then three more, then five more, for a total of twelve in one week.

The Fair Play Committee's position was controversial among Japanese Americans at Heart Mountain, and was vigorously debated in camp and elsewhere. Editorials and letters deeply critical of the organization's agenda appeared in the Heart Mountain Sentinel , the camp's newspaper. At the same time, James Omura , the English-language editor of the Denver newspaper Rocky Shimpo , published stories that praised the Fair Play Committee for its stand and criticized both the government and elements within the Japanese American community that opposed the organization.

For much of the month of March, it appeared that the government would not move against the Fair Play Committee. The young men who refused to report for their physicals went about their business unmolested, and when the Fair Play Committee defied the WRA's prohibition of further public meetings, the WRA did not interfere. However, at the end of the month, things changed dramatically. Agents from the U.S. Marshals Service swept through the camp and arrested the young men who had refused to appear for their physicals, charging them with willful evasion of the draft and carting them off to local jails. Camp administrators also nabbed Kiyoshi Okamoto, subjected him to a hearing about his suitability for a leave from camp that he had not requested, and shipped him off to the Tule Lake Segregation Center .

Arrest, Trial, and Imprisonment

By June of 1944, sixty-three young members of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee had resisted the draft and been arrested. They were tried in the largest mass trial in Wyoming's history in a federal district court in Cheyenne, Wyoming, before Judge T. Blake Kennedy. Kennedy had little patience for the defense's efforts to plead the unlawfulness of the mass removal and incarceration of the Nisei as a defense to the crime of willfully defying an order to report for military service. He convicted all sixty-three after a short trial and sentenced them to three years of jail time, which the younger defendants served at the McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary near Tacoma, Washington, and the older served at the Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary in Kansas. Later that year, the United States Circuit Court for the Tenth Circuit in Denver affirmed their convictions and sentences on appeal. The defendants served out their jail terms, for the most part not returning home until 1946.

The successful prosecution of these 63 Nisei (and 22 others who resisted the draft after the Cheyenne trial concluded) did not reach most of the top echelon of leadership of the Fair Play Committee, because they were older men who had never received draft notices and therefore could not be charged with refusing the draft. The government solved this problem by charging that group—Okamoto, Emi, Nakadate, and several others—with illegally conspiring with each other and with Rocky Shimpo newspaperman James Omura to counsel others to commit the felony of evading the draft. Their case came to trial before a federal district court jury in Cheyenne in October of 1944. The jury convicted all of them except for Omura. It is often asserted that the jury acquitted him because he was a journalist exercising his First Amendment right to freedom of the press, but the historical record suggests that the jury's real reason was that they simply did not believe the government had presented enough evidence to link him to the other defendants' conspiracy.

The convicted leadership of the Fair Play Committee were sentenced to jail terms of four years in the case of those the court saw as more culpable (including Okamoto, Emi, and Nakadate) and two years for those less culpable. In 1945, however, the federal Court of Appeals in Denver overturned their convictions because of an error that the trial court had made in the phrasing of the legal instructions submitted to the jury. Although federal prosecutors could have retried the men, they chose not to do so.

After the War

In December of 1947, President Harry S. Truman granted the convicted members of the Fair Play Committee (and the draft resisters from the other WRA camps) a full pardon on the recommendation of an amnesty board headed by former Supreme Court Associate Justice Owen Roberts. Forgiveness within the Japanese American community was much longer in coming. For decades after the war, the draft resisters from Heart Mountain (like those from the other camps) were shunned and criticized by many in the larger community, including many U.S. Army veterans and members of the Japanese American Citizens League . Many in the Japanese American community also erroneously referred to them as " no-no boys ," people who in 1943 had refused to avow loyalty to the United States on their loyalty questionnaires. The Fair Play Committee was an avowedly patriotic and loyal resistance movement; young men who had answered "no" to Questions 27 and 28 on their loyalty questionnaires were barred from membership.

It was not until the 1990s that some (though not all) Japanese American veterans' groups came to express an awareness of the loyalty and courage shown by the members of the Fair Play Committee in demanding the restoration of Nisei rights as a precondition for military service. In 2000, the Japanese American Citizens League adopted—by a sharply divided vote—a resolution of apology to the resisters for decades of ostracism.

For More Information

Abe, Frank. Conscience and the Constitution . DVD. Transit Media, 2011.

Mackey, Mike, ed. A Matter of Conscience: Essays on the World War II Heart Mountain Draft Resistance Movement . Powell, Wyoming: Western History Publications, 2002.

Muller, Eric L. Free to Die for their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters in World War II . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Nelson, Douglas W. Heart Mountain: The History of an American Concentration Camp . Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1976.

Last updated March 11, 2024, 9:10 p.m..

Media

Media