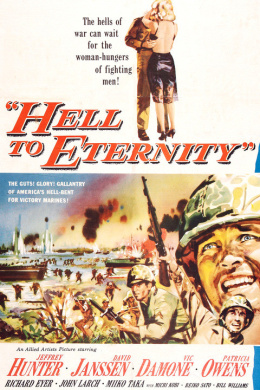

Hell to Eternity (film)

| Title | Hell to Eternity |

|---|---|

| Date | 1960 |

| Director | Phil Karlson |

| Producer | Irving H. Levin |

| Screenplay | Ted Sherdeman |

| Starring | Jeffrey Hunter (Guy Gabaldon); David Janssen (Sgt. Bill Hazen); Vic Damone (Cpl. Pete Lewis); Patricia Owens (Sheila Lincoln) |

| Music | Leith Stevens |

| Cinematography | Burnett Guffey |

| Editing | Roy V. Livingston; George White |

| Studio | Allied Artists Pictures |

| Runtime | 131 minutes |

| Budget | $800,000 |

| Gross | $2.8 million |

| IMDB | Hell to Eternity |

Hell to Eternity , directed by Phil Karlson and released in 1960, is a Hollywood war film that dramatizes the real-life story of Guy Gabaldon (played by Jeffrey Hunter), an American Marine who singlehandedly captured over 1,500 Japanese soldiers and civilians on the Island of Saipan during the fighting there in mid-1944. In addition to its portrait of Gabaldon's wartime heroism, Hell to Eternity is notable as the first Hollywood film to portray the wartime confinement of Japanese Americans.

Background of Film

The story of Guy Gabaldon and his wartime exploits on Saipan remained largely unknown to the public until 1957, when Gabaldon was a guest on Ralph Edwards's popular television show This is Your Life . After his appearance, producer Irving H. Levin and screenwriter Bill Doud began work on a screen adaptation. (Following Doud's death, Ted Sherdeman took over as writer). After two years of effort, they made a deal with Allied Artists (formerly Monogram Pictures) a low-budget motion picture production company to make the adaptation. Hollywood veteran Phil Karlson was signed to direct.

Plot

The boy Guy Gabaldon (Richard Eyer), a troubled child of the ghetto in 1930s Los Angeles, is taken in by the Unes, a local Japanese American family. The Unes adopt Guy following his parents' deaths, and raise him alongside their Nisei sons George (George Matsui) and Kaz (George Shibata). Guy's Issei foster mother (played by the famed silent film star Tsuru Aoki Hayakawa, in her only sound film role) teaches him to speak Japanese, so they may communicate, and he in turn starts teaching her English. Her tenderness succeeds in winning his avowal of love for her.

The film then jumps forward to Pearl Harbor. Following the attack, Guy is alienated by the discrimination he sees. He goes out on a (platonic) date with his brother George's girlfriend Esther (Miiko Taka) and gets harassed by racist toughs. Meanwhile, his Nisei brother George (George Takei) attempts to enlist, and is refused. [1] Ultimately, the Une family and their neighbors are removed by the army and sent to camp. Outraged by the mistreatment of his family and rejected for service in the army due to a perforated eardrum, Guy becomes despondent. After learning from George that the authorities have transferred his Isssi foster parents to "Camp Manzanar" (implicitly away from other "regular" camps) because of his father's delicate health, Guy pays them a surprise visit. Mama Une tells him that his Nisei brothers have volunteered for military service in order to make a better world, and tells him that he too should find some way to join. Inspired, Guy enlists in the marines, where he is accepted due to his language skills.

Guy's first stop is in Hawai'i. There, along with his buddies Bill and Pete (played by David Janssen and Vic Damone), he dates a blonde war correspondent and a pair of Nisei bar hostesses (one of whom does a striptease, somewhat cut down for the censors). He then arrives in Saipan during the bloody fighting. At first, Guy is paralyzed by fear under fire, and horrified to see local Japanese civilians ordered by Imperial troops to commit suicide by jumping off cliffs—he imagines that it could be the Unes. Enraged by the killing of his comrade Bill, he then becomes driven by thoughts of revenge against the Japanese soldiers. Guy is ultimately able to meet with the general of the Japanese troops (played by famed ex-silent star Sessue Hayakawa), whom he persuades to surrender his hopelessly outnumbered forces, thereby preventing a bloody battle and the death of more civilians. The film ends with Guy leading singlehandedly the masses of prisoners who have surrendered.

Dramatic License and Japanese American Legacy

The film, while founded in reality, diverges in some important respects from the actual facts. First, while the blue-eyed Anglo actor Jeffrey Hunter (who was also a head taller than his subject) played the lead, Gabaldon was in fact Mexican-American. The film not only excludes all reference to Guy's Hispanic culture, but his birth family is erased. In reality, while Gabaldon established a close relationship as a teenager with the Nisei brothers Lyle and Lane Nakano, and moved into the Nakanos' house as a surrogate son, he was not orphaned and he remained connected to his parents. What is more, he learned "street Japanese," by his own estimation, and never became fluent in the language. Finally, while Gabladon did indeed try to enlist in the armed forces after Lyle and Lane Nakano joined the army, and was initially rejected, the refusal was not solely for medical reasons, but also because he was then underage.

Hell to Eternity is centered on Guy Gabaldon's experience, and the Issei and Nisei characters are secondary figures, who all disappear midway through the film. Yet in many respects it stands as one of the first mainstream Japanese American movies (along with the 1951 film Go For Broke! and The Crimson Kimono from 1959). It portrays in positive, if somewhat idealized terms, a representative Nikkei family, and takes up the question of their assimilation. When the teenage Guy comes to the Une house, he is fearful of their foreign ways, especially after George teases him by describing the exotic food they eat. He is then relieved to discover that they are in fact typically American in their diet and habits.

More importantly, Hell to Eternity is the first Hollywood film (apart from the "documentary" scenes in Little Tokyo U.S.A. (1942)) to portray mass wartime removal. Guy, Kaz, George, and his Nisei girlfriend Esther watch Japanese Americans quietly leaving their houses and being loaded on trucks for Santa Anita . Guy is the only one to express outrage or opposition. When George mentions that they are going to "relocation camps," Guy snorts, "more like concentration camps." Esther pleads with him not to blame the Japanese Americans for following orders and says that at least in the camps they will not face bigotry as "Japanese." Guy snaps, "But you're not Japanese, you're Americans." He then asks big brother Kaz how the government could treat Japanese Americans this way, but not Italians or Germans. His brother responds, "I can't answer that. Right or wrong, our government's doing what they think is right. No one bats 1.000."

The film also offers the first-ever representation of the War Relocation Authority camps in Hollywood cinema, in the scene where Guy goes to visit his Issei foster parents at Manzanar . Perhaps because the film was produced not long after the war, and the producers needed to stay in the good graces of the army to obtain their assistance in making the film, the presentation of the camps is greatly sanitized. After a quick establishing shot of barracks in a verdant valley, what is portrayed is a small but comfortable room. There is no suggestion that the entire family is housed in one 20'x 25' shack; instead, there is an inner door, which suggests other rooms or a closet. There is shown inside a window with curtains, a table and chairs, a bureau with knickknacks, and a side table with photos. Outside is a trellis with vines. When Guy sees Mrs. Une, she is puttering around the house cleaning (no dust storms are mentioned) and Guy is pleased to see that Mr. Une has been strengthened by his time at Manzanar. However, the costs of removal are not minimized. Mrs. Une laments that the house and everything else that she and her husband had has been lost: "Mother, father of Une family work hard all lives build good... foundation for future. Not many years left for old people to build again."

Hell to Eternity was released in Summer 1960, and was a commercial success—rentals in North America alone reached $2,800,000, for a film with an $800,000 budget. Mainstream response to the film was quite positive overall, and centered on the realism of the combat scenes. A review in The New York Times praised the film as "tough, thoughtful and, especially in one extended battle sequence, tingling." [2] A modern-day critic extolls the film as foreshadowing later independent cinema: "a rowdy, dirty-minded, defiantly deromanticized film that's a fascinating marker in the era of the decline of the old studios and the oncoming age of a new realism." [3] Curiously, even as mainstream newspapers overlooked the Japanese American aspect of the film, Japanese community newspapers proved spotty in their coverage. Pacific Citizen did not even run a review of the film. Unlike Samuel Fuller's contemporaneous features, Hell to Eternity has remained a footnote in Asian American film history.

Related Articles

For More Information

Hell to Eternity trailer. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mEuPUUB5Vek

Banks, Taunya Lovell. "Outsider Citizens: Film Narratives About the Internment of Japanese Americans." Suffolk University Law Review 42 (2009): 769–94 .

Creef, Elena Tajima. Imaging Japanese America: The Visual Construction of Citizenship, Nation, and the Body . New York: New York University Press, 2004.

Robinson, Greg. "Parallel Wars: Japanese American and Japanese Canadian Internment Films." DiscoverNikkei , Jan. 26, 2010 .

Takei, George. To the Stars: The Autobiography of George Takei Star Trek’s Mr. Sulu . New York: Pocket Books, 1994.

Footnotes

- ↑ Ironically, Guy's brother Kaz, who is also refused the chance to serve, is played by George Shibata, a Nisei from Utah (who lived in the "free zone" and was not sent to camp during World War II) who became the first Nisei West Pointer after the war.

- ↑ Howard Thompson, "Hell to Eternity is Story of Marine Hero," The New York Times , October 13, 1960.

- ↑ "Hell to Eternity," in Ferdy on Films, accessed on January 30, 2015.

Last updated March 11, 2024, 11:28 p.m..

Media

Media