Japanese American Creed

Statement written by Mike Masaoka of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) in 1941 that was meant to affirm Japanese American patriotism at a time when war with Japan was on the horizon. In the coming years, it would be frequently read and cited at JACL events and by non-Japanese American supporters. Symbolic of the JACL philosophy for many, the statement had both avid supporters and critics. Its proposed inclusion on the National Japanese American Memorial in Washington DC in the 1990s was controversial and brought renewed attention to the creed.

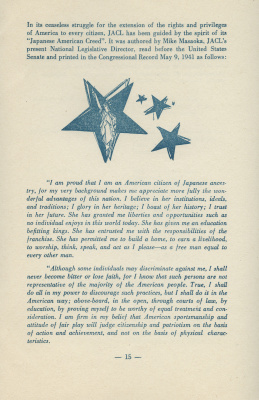

The creed was written by Mike Masaoka, then the chairman of the Intermountain District Council and national board member of the JACL, before he was hired as the league's first paid staff person. According to his autobiography, the creed came about as a result of a blank page that needed content in a printed program for a JACL district convention in Salt Lake City. "What I had in mind was a statement about what my country meant to me," he wrote. "What I came up with in one furious writing session was a credo, a statement from the heart that told what Americanism meant to a Japanese American." [1] It read as follows:

I am proud that I am an American citizen of Japanese ancestry, for my very background makes me appreciate more fully the wonderful advantages of this Nation. I believe in her institutions, ideals, and traditions; I glory in her heritage; I boast of her history; I trust in her future. She has granted me liberties and opportunities such as no individual enjoys in this world today. She has given me an education befitting kings. She has entrusted me with the responsibilities of the franchise. She has permitted me to build a home, to earn a livelihood, to worship, think, speak, and act as I please—as a free man equal to every other man.

Although some individuals may discriminate against me, I shall never become bitter or lose faith, for I know that such persons are not representative of the majority of the American people. True, I shall do all in my power to discourage such practices, but I shall do it in the American way--above board, in the open, through courts of law, by education, by proving myself to be worthy of equal treatment and consideration. I am firm in my belief that American sportsmanship and attitude of fair play will judge citizenship and patriotism on the basis of action and achievement, and not on the basis of physical characteristics.

Because I believe in America and I trust she believes in me, and because I have received innumerable benefits from her, I pledge myself to do honor to her at all times and in all places; to support her constitution; to obey her laws; to respect her flag; to defend her against all enemies, foreign or domestic; to actively assume my duties and obligations as a citizen, cheerfully and without any reservations whatsoever, in the hope that I may become a better American in a greater America.

The statement struck a chord with many JACL members. Masaoka's friend and mentor, Senator Elbert Thomas of Utah, read the creed into the Congressional Record on May 9, 1941. The JACL distributed copies of the creed widely, focusing on government officials, organizations sympathetic to Japanese Americans, the media, and anyone else thought to be in a position to influence policy on Japanese Americans. The JACL adopted it as its official creed at its 1946 convention. [2]

Over the next decade plus, the creed was often cited by both the JACL and by those seeking a quick way to assert Japanese American patriotism. Magazines ranging from Common Ground to Reader's Digest printed all or part of the creed, and white community leaders seeking to praise Japanese American "loyalty" cited it in speeches. [3] It was read regularly at many JACL events of the 1940s and 1950s and framed copies of it were passed out as gifts to friends and supporters. [4] Dr. James T. Taguchi, president of the Dayton JACL, read it to music on a 1952 local television appearance. [5] It was even plagiarized. At a 1945 rally spurred by anti-Japanese activity directed at the family of Kazuo Masuda , a decorated Nisei soldier who had been killed in Europe, actor Richard Loo read the "Chinese American Creed," which turned out to be an ethnically adapted version of the Japanese American Creed. [6]

But many Japanese Americans objected to aspects of the creed, those objections coming to the forefront as dissident views of the incarceration began to emerge in the 1970s in the context of the Redress Movement . Redress activist William Hohri called the creed an "apologetic self-declaration of imagined racial or ethnic inferiority and a promise of complete submission to and utter trust in the white majority." Another redress proponent, Shosuke Sasaki called it "the most disgusting confession or declaration of inferiority that I've ever seen." Henry Miyatake , blithely paraphrased the creed as "You can treat us like crap, but we're still going to be loyal." Recognizing the changing times, a resolution to "retire" the creed was introduced at the 1974 JACL convention in Portland, Oregon. But after heated debate, the proposal was defeated by a 45–29 vote. Masaoka acknowledged in his 1987 autobiography that "In these cynical times such a statement might appear maudlin." [7]

The creed gained renewed attention in the late 1990s, when plans for a National Japanese American Memorial in Washington, DC were being made. In its proposed design for the memorial, the NJAM board included a quotation from the Japanese American Creed among the inscriptions on it. This proposal led to much protest and a split in the NJAM board, as several board members openly disagreed with including Masaoka's words. The Committee for a Fair and Accurate Memorial petitioned the National Park Service to remove the excerpt from the creed and led a campaign that received wide coverage in the mainstream media. They also started the JAvoice.com website, which came to include not only material on the memorial controversy, but many other documents representing dissident perspectives of the wartime incarceration. Despite these protests, Masaoka's words did end up being inscribed on the memorial, which was dedicated as the Memorial to Japanese-American Patriotism in World War II in 2000. [8]

For More Information

Daniels, Roger. Concentration Camps, U.S.A.: Japanese Americans and World War II . New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971.

Hosokawa, Bill. JACL in Quest of Justice: The History of the Japanese American Citizens League . New York: William Morrow, 1982.

Masaoka, Mike, and Bill Hosokawa. They Call Me Moses Masaoka . New York: William Morrow, 1987.

Murray, Alice Yang. Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress . Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008.

Footnotes

- ↑ Mike Masaoka and Bill Hosokawa , They Call Me Moses Masaoka (New York: William Morrow, 1987), 49–50.

- ↑ Masaoka and Hosokawa, They Call Me Moses , 50–51; Ellen Wu, The Color of Success: Asian Americans and the Origins of the Model Minority (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), 76.

- ↑ The pro-minority quarterly Common Ground printed the entire creed in is Spring 1942 issue, which can be viewed online at http://www.unz.org/Pub/CommonGround-1942q1-00011 . The creed is cited in an article on Masaoka by Alfred Steinberg ("Washington's Most Successful Lobbyist: Mike Masaoka," 125–29) in the May 1949 issue of Reader's Digest . To cite but a couple of examples of such speeches, General Joseph W. Stilwell concluded his speech at a May 9, 1946 event honoring him sponsored by the San Francisco JACL by calling on "all Nisei to live up to the Japanese American Creed." At speech at the banquet of the Washington, DC JACL chapter on September 22, 1946, former War Relocation Authority Director Dillon S. Myer concluded by stating, "Remember the Japanese American creed. If you can live up to 75 per cent of it, you're doing well. If you live up to 100 per cent of it, all the better." Pacific Citizen , May 11, 1946, 3 and Sept. 28, 1946, 5, both accessed online on Jan. 11, 2018 at http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-pc-18-19/ and http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-pc-18-39/ .

- ↑ For examples of such events, see the Pacific Citizen , May 18, 1946, 7; Sept. 2, 1950, 8; and June 3, 1955, 4, all accessed on Jan. 11, 2018 at http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-pc-18-20/ , http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-pc-22-35/ , and http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-pc-27-22/ . A framed copy of the creed was given to Rt. Rev. Monsgr. Nicholas H. Wegner, director of Boys Town in Nebraska in August 1951 and "hand-engraved" copies to honorees at a JACL Intermountain District Council dinner on November 24, 1951. See Pacific Citizen , Aug. 18, 1951, 3 and Dec. 1, 1951, 1, accessed on Jan. 11, 2018 at http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-pc-23-33/ and http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-pc-23-48/ .

- ↑ Pacific Citizen , July 15, 1950, 3, accessed on Jan. 11, 2018 at http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-pc-22-28/ .

- ↑ Pacific Citizen , Dec. 15, 1945, 2, accessed on Jan. 11, 2018 at http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-pc-17-50/ . Loo claimed not to know the origin of the "Chinese American Creed."

- ↑ Hohri quote cited in Alice Yang Murray, Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008), 304; Shosuke Sasaki interview by Frank Abe and Stephen Fujita, May 18, 1997, Segment 23, Densho Archives; Henry Miyatake quote cited in Robert Sadamu Shimabukuro, Born in Seattle: The Campaign for Japanese American Redress (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001), 13; Pacific Citizen , Aug. 9, 1974, 3, 5; Masaoka and Hosokawa, They Call Me Moses , 49.

- ↑ Murray, Historical Memories , 421–26.

Last updated July 7, 2020, 7:45 p.m..

Media

Media