Joe Kobuki

| Name | Yoshio "Kokomo Joe" Kobuki |

|---|---|

| Born | 1918 |

| Died | 1997 |

| Birth Location | WA |

| Generational Identifier |

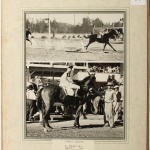

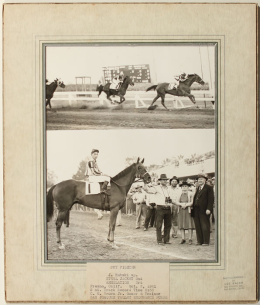

Yoshio "Kokomo Joe" Kobuki, the first Japanese American jockey in the U.S., rose from lowly stable boy to the reigning jockey star at California fairs and the bush leagues of racing in the summer of 1941. In the fall of 1941, he set what was then a horse racing record, winning seven races in a row at the Humboldt County Fair. But even his flight into the Sonoran Desert failed to protect him from the government's roundup and incarceration of Japanese Americans. After three years of confinement at Poston , he tried to return to racing, only to fall victim to still-rampant racism, a career ending injury, and cancer.

Beginnings

Yoshio Kobuki was born in the White River Valley east of Seattle in 1918. He was so small that his father joked he could carry him in the pocket of his suit coat. Just weeks after his birth, his mother died in the influenza pandemic of that year, and his father sent Yoshio and three siblings to Japan to be raised by an aunt. There, Yoshio read American movie magazines and dreamed of returning to the land of his birth, where rich men and movie stars with engaging smiles rode in chauffeured limousines and smoked long cigarettes.

When Kobuki finally returned to the U.S. as a teenager in 1934, he weighed less than 100 pounds and wasn't five feet tall. After a short period as a chauffeur in the Seattle area, he headed south for Los Angeles in search of the fame he had read and dreamed about. There were no Japanese American jockeys in racing, but encouraged by his size and his burning ambition he found himself at Santa Anita Race Track in search of work "guiding the horse." In the shedrows, where his awkward English and his strange name were laughed at, they hung the nickname "Kokomo Joe" on him. The name had the sound and promise of sports fame. But despite a broad smile he had learned from American magazines, the only work Kokomo Joe could find at Santa Anita was mucking stalls and hot-walking horses. It was a long way from the American fame he had dreamed of having one day. [1]

The Bush Leagues

Advised by trainers at Santa Anita to go to the bush leagues to learn to ride, Kokomo Joe left Los Angeles for the Fairgrounds in Phoenix, where he got only long shot mounts. But a small-time owner and trainer named Charley Brown recognized Kokomo Joe's potential and signed him to a contract. In April of 1941, at Caliente Race Track in Tijuana, what the newspapers were calling "the first Japanese jockey in the U.S." had his first victory. Others followed quickly.

Encouraged by the success of his new jockey, and with a string of a dozen sturdy runners, some of whom he started every other day, Charley Brown headed with Kokomo Joe for the northern California fair circuit in the summer of 1941. Against a backdrop of increasingly ominous war news, Kokomo Joe began winning races frequently. He was tied for the jockeys' lead entering the last day of racing at Pleasanton in the Bay Area. But his ever-present smile, which he felt was the passkey to American success, irritated fellow jockeys, who mistook his awkwardness with English for an aloofness. His frequent victories were also irritating and had drawn punches in the jockeys' room. That last day of racing at Pleasanton, those same jockeys boxed him in or cut him off in the stretch and managed to keep him out of the winner's circle and deprive him of the riding title.

By the time he and Charley Brown arrived in August at the Sonoma County Fair in Santa Rosa, Kokomo Joe had learned how to avoid the efforts to block him, and he won the meet. Then he and Brown went to the tiny northern California coastal town of Ferndale, site of the Humboldt County Fair. There, Kokomo Joe won seven straight races over three days of racing. The grooms and hot walkers insisted it was a racing record. Buoyed by his successes, he was the leading rider at the Sacramento Fair in September. Despite the increasing talk of war, especially against Japan, California turf writers called Kokomo Joe a "rising star" in the world of racing. They described him as a "package of Nipponese dynamite." It was only a matter of time, they said, before he would be winning races at Hollywood Park, earning the admiration and attention of those very same movie stars he had once read about in Japan.

That fall Kokomo Joe and Charley Brown went back to Caliente. It was an opportunity for Kokomo Joe to polish his riding skills before he went north with Charley Brown for the meet at Santa Anita, where they had once mocked him in the shedrows. This time, there was every indication he would be honored. [2]

Incarceration and the End

Late in the afternoon of Sunday, December 7, 1941 , he sat in the jockeys' room at Caliente preparing for his last mount of the day. Suddenly, track stewards rushed into the room to announce that the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor. They said that Mexican police were arresting all Japanese. If Kokomo Joe wanted to avoid a hell-hole prison in Mexico, he needed to get back on U.S. soil.

Six months later, as war news from the South Pacific worsened, and invasion fears and anti-Japanese feelings mounted on the West Coast, Kokomo Joe was one of 110,000 "persons of Japanese ancestry"—most of them American citizens like himself—who were expelled and then confined in various "relocation" camps. Kokomo Joe wound up in an Arizona camp called Poston in the hell-hole of the Sonoran Desert for the duration of the war.

He was not released until late 1945. Nearly four years of his racing life had been taken from him. In the postwar anti-Japanese climate, even his attempt to return to racing after he was released proved futile. In 1946 in Canada, where excluded Japanese had still not been allowed to return to the coast, the Mounties nearly arrested him at Exhibition Park. The few long shot mounts he could get in 1946 and 1947 at Waitsburg, Walla Walla, and Gresham Park in Oregon finished out of the money.

Finally, to keep his riding talents alive while he waited for the country's wartime hostilities to fade, Kokomo Joe went back to the Sonoran Desert where he had been imprisoned, this time to exercise horses on a ranch out of Gila Bend. But one dawn on the exercise track, another exercise rider, still harboring wartime anti-Japanese feelings, forced him into the rail. He broke his leg and his hip, and after almost a year in the hospital in traction, his broken leg had frozen at the knee and he could not bend it to mount a horse. Eventually, they mocked him again, this time for being a laughable imitation of the popular stiff-legged "Chester" from TV's "Gunsmoke." His racing days were over. The promise of jockey stardom was gone.

Kokomo Joe hung around racetracks the rest of his life as a parking attendant , a far cry from the magazine glamour he had dreamed of. He spent his last years before his death living alone in a small trailer on a farm in Galt, California, where he died in 1997. [3]

For More Information

Christgau, John. KOKOMO JOE: The Story of the First Japanese American Jockey in the U.S. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

Footnotes

- ↑ Telephone interview with Elsie and Jiro Kobuki, May 17, 2006; notes of interview with Elsie and Jiro Kobuki, Mesquite, Nevada, September 24, 2006; "Certificate of Birth, #813," Yoshio Kobuki , Washington State Board of Health, October 18, 1918; "Individual Record, Yoshio Kobuki," Evacuee Case Files 1942-46, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), War Relocation Authority, Record Group 210; "Arizona Stables To Make Bid For Horse Race Wins," Arizona Republic , January 11, 1941; Daily Racing Form, Editors, The American Racing Manual (ARM): Edition of 1941 , 97 (Chicago: Triangle Publications: 1941); ARM, Edition of 1940 , 584; "Colorful Border Season," San Diego Union , August 31, 1939; transcription of taped interview with T.A. and Jan Farrell, Galt, California, March 8, 2006.

- ↑ The Bush Leagues "Kobuki To Ride At Pleasanton Race Meeting," Rafu Shimpo , July 6, 1941; "Very Truly Yours," Rafu Shimpo, July 13, 1941; "It's County Fair With Slick Finish," San Francisco Chronicle , July 3, 1941; "4000 Fans Set Opening Day Bet Record At Pleasanton," Oakland Tribune , July 4, 1941; "Santa Rosa Results," San Francisco Chronicle , August 3, 1941; "Michaelmas And His Japanese Jockey," Stockton Record , August 13, 1941; "$161 Record Payoff Made at Santa Rosa," San Francisco Examiner , August 5, 1941; "More Racing and Evening Program Awaited at Fair," Humboldt Times , August 15, 1941; "Fast Track, Good Weather Mark Opening Of Race Meet," Ferndale Enterprise , August 15, 1941; "Kokomo Joe Kubuki (sic) Sets Records," "Ferndale Race Results," Humboldt Times , August 16, 1941.

- ↑ Interview with David Beltran, November 5, 2007, Chula Vista, California; telephone interview with Francisco "Pancho" Rodriguez, September 4, 2007; transcription of interviews with jockey Junior Nicholson, Pleasanton, California, November 14, 2002, March 3, 2003; Donald H. and Matthew T. Estes, "Further and Further Away: The Relocation of San Diego's Nikkei Community, 1942," http://www.jahssd.org/cgi-bin/page2.cgi?donarticles ; Morton Grodzins, Americans Betrayed: Politics and the Japanese Evacuation , 4, 265-266 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1949); Francis Biddle, In Brief Authority , 110, 115, 126 (New York: Doubleday & Company, 1962); James H. Rowe interviewed by the Earl Warren Oral History Project, "The Japanese Evacuation Decision," Japanese-American Relocation Reviewed: Volume I, Decision and Exodus , 29 (Berkeley: University of California, 1976); Matthew T. Estes and Donald H. Estes, "Hot Enough to Melt," www.jahssd.org; "Nisei In Arizona," Pacific Citizen , June 26, 1948; "Vital Statistics" Camp Harmony Newsletter , July 10, 1942, University of Washington Libraries, lib.washing.edu/exhibits/harmony/exhibit/cycle.html; "Statistics, Profile, Summary," Poston Series #5, Block #15, Cornell University, Carl Kroch Library; "Burdick in Move to Clarify Status of Kitchen Workers," Poston Press Bulletin , September 26, 1942; "Final Coroner's Report of Investigation—Joe Kobuki," Sacramento County Coroner, March 24, 1997; Elsie and Jiro Kobuki interview, May 17, September 24, 2006; T.A. and Jan Farrell interview , March 8, 2006; "Joe Kobuki Scrapbook," courtesy of Elsie and Jiro Kobuki.

Last updated March 19, 2013, 6:58 p.m..

Media

Media