Kenjinkai

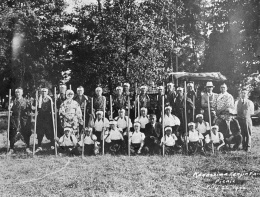

Issei immigrants often organized and joined prefectural associations called kenjinkai for mutual aid in time of illness or death, as well as for various kinds of misfortune. Ken refers to the prefecture from which the immigrants came in Japan. Particularly during the early years of immigration when most Japanese were single men, the kenjinkai provided collective assistance to individuals from the same ken or prefecture in Japan. In both Hawai'i and the Mainland, kenjinkai provided aid, fellowship, and a sense of community for immigrant workers thousands of miles from Japan. [1]

Background of Kenjinkai

Large prefectural groups often organized numerous local clubs for those from the same village, town, or county for mutual aid and fellowship. In most instances such local clubs were formed before the kenjinkai were organized. Some kenjinkai were established when a need arose; for instance, Etsuyukai (Association of Friends from Echigo Province) was formed when the immigrants from Niigata-ken began to migrate to different parts of the island of Hawai'i. The Niigata Kenjinkai of Honolulu was organized in 1909 with 205 members to help unify Niigata immigrants on O'ahu. The origin of its formation is explained by Rinji Maeyama:

The Niigata Kenjin-kai of Honolulu was organized to collect donations from those from Niigata-ken to buy a set of new clothes for a man from our ken who committed murder and was sentenced to death. Those from Niigata-ken felt that he should at least wear respectable clothes to end his life. After that, when there were some sailors of Niigata-ken background on the Japanese naval training ships which visited Honolulu, our Kenjin-kai gave a welcome party for them. [2]

While immigrants from Niigata and Kagoshima had little difficulty establishing independent kenjinkai because of their small numbers, the large number of Japanese from Hiroshima and Yamaguchi made it difficult for these clubs to organize themselves. According to scholar Yukiko Kimura, "While their locality clubs provided them mutual identification and assistance at the village and town levels, they tended to be rather impersonal and even competitive on the prefectural level." [3] While different kenjinkai existed for immigrants from Hiroshima and Yamaguchi, there was no one organizing entity that united all the immigrants from these two regions.

The kenjinkai provided the means for not only mutual assistance and aid but also social opportunities for people who shared the same dialects and experiences. Although some Issei were never a part of any kenjinkai because their prefectural groups were too small to organize, the kenjinkai was an essential part of the Issei experience. Even when the Nisei joined their parents' kenjinkai , they did not share the memories of the prefecture or the needs that brought the immigrants together.

Transformation of the Kenjinkai

Prior to World War II, kenjinkai were primarily limited to immigrants from the same prefecture. However, after the war, many kenjinkai became more open in membership and "Americanized" in name and activities. For example, the Hiroshima Gōyū Kai became the Shinyū Aloha Kai after the war. Along with the name, membership rules were changed. Even today, many organizations—particularly those in Hawai'i—hold kenjinkai picnics where multi-generation Japanese Americans attend and speak a mixture of Japanese and English, sing popular tunes and folksongs, play favorite games and pastimes, and celebrate an ever-evolving Japanese American culture. Scholar Dennis Ogawa points out that "rather than only trying to rekindle affections for Japan," these picnics and events organized by the kenjinkai currently "serve to bring Island communities or organizations together." [4] Yet as the political and cultural landscape of Japanese American communities both in Hawai'i and the Mainland shifts away from the past, the challenge facing many kenjinkai today is maintaining their relevance for future generations.

For More Information

Haenschke, Kristine. "Does the Kenjinkai Have a Future." Discover Nikkei , May 6, 2009. http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2009/5/6/kenjinkai/

Sekiya, Raymond T. "Celebrating Roots in Fukuoka." Hawaii Herald 32: 2 (January 21, 2011): 6-7.

Yoshinaga, Ida. "Staying Alive, Part II." Hawaii Herald 17:6 (March 15, 1996): A-16, 17.

Footnotes

- ↑ Research for this article was supported by a grant from the Hawai‘i Council for the Humanities .

- ↑ Yukiko Kimura, Issei: Japanese Immigrants in Hawaii (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1988), 25-26.

- ↑ Ibid., 27.

- ↑ Dennis M. Ogawa, Jan Ken Po: The World of Hawaii′s Japanese Americans (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1973), 10.

Last updated June 10, 2015, 1:18 a.m..

Media

Media