Marysville (detention facility)

| US Gov Name | Marysville Assembly Center, California |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | Temporary Assembly Center |

| Administrative Agency | Wartime Civil Control Administration |

| Location | Marysville, California (39.0500 lat, -121.5500 lng) |

| Date Opened | May 8, 1942 |

| Date Closed | June 29, 1942 |

| Population Description | Held people from Placer and Sacramento Counties, California. |

| General Description | Located about 5 miles southeast of Marysville, California. |

| Peak Population | 2,451 (1942-06-02) |

| Exit Destination | Tule Lake |

| National Park Service Info | |

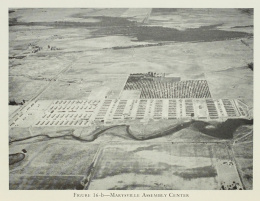

The Marysville Assembly Center—also known as "Arboga"—was built on a migrant worker camp about five miles southeast of Marysville. The least populous " assembly center " other than Meyer, Arizona , Marysville had a peak population of just 2,451. Its population came almost entirely from two nearby and mostly rural areas: Placer County, just southeast of Marysville, and Florin, a notable Japanese American agricultural community south of Sacramento. Open for a total of just fifty-three days in May and June of 1942, Marysville had relatively limited recreational programs and no schools to speak of, along with some of the worst physical conditions of any assembly center: heat and humidity, a serious mosquito problem, and unpartitioned pit toilets, among other things. Essentially the entire population of the camp was transferred to Tule Lake in the last week of June.

Site History/Layout/Facilities

The camp was built on the Arboga Colony, a 160-acre site owned by Yuba County Reclamation District 784. Construction began on March 27, but was hampered by heavy rain and mud. Built "on a foundation of mud," many of the barracks had uneven floors as a result and doors that were difficult to open. The rains also left pools of standing water that were breeding grounds for mosquitoes. "Lots of gnats and mosquitoes, terrible," recalled playwright Hiroshi Kashiwagi in a 1992 interview. Another inmate remembered that mosquitoes would come out from under the floorboards, requiring "netting on the floor to keep the mosquitoes out." Taketora Jim Tanaka recalled that "you turned that light on, about forty-five minutes, there was so much bugs in there, you couldn't even see the light bulb." In his memoir, Kashiwagi wrote, "Though hardly stylish at the time, many women and girls wore pants and slacks out of sheer necessity to protect themselves from the insects. But angry, unsightly welts on legs, arms, necks, even faces were not uncommon." [1]

The camp was divided into six blocks , each consisting of twenty 20 x 100 foot barracks, along with a mess hall, bath house and latrine. Four additional barracks were set aside for recreation and two became the hospital. As in WRA camps, the residential barracks were wood structures that were subdivided into multiple "apartments" (labeled "A" through "E") with the dividing walls stopping short of the roof, allowing sounds to travel across a barracks. Units were identified by the block number, barrack number, and apartment letter, e.g. "5-1-A." As at other assembly centers, regular head counts of inmates took place, in the case of Marysville, starting on June 8 at 8 pm, at which point all inmates had to be in their assigned units. [2]

In addition to the standard "assembly center" maladies, the buildings at Marysville also had electrical problems due to what first camp manager Paul D. Shriver called "bad installation of electric lighting facilities." This resulted in the constant burning out of fuses and light bulbs that required inmates to not use other electric equipment when the lights were on. The electrical issues, combined with the barracks' wooden construction and the distance from a full fire department left Shriver worried about "a bad fire" that could "destroy the entire center in a short while, particularly if there is a bad wind." [3]

There were six mess halls, one to a block, each with a capacity of 165. As with other assembly centers with rural populations, the lack of inmates with professional cooking experience led to staffing problems in the mess hall kitchens. "Due to the fact that evacuees were drawn from rural areas there were not sufficient cooks," wrote Shriver in a weekly report, adding that the "few cooks and helpers that were available lacked experience in mass fooding and it required a formidable effort on the part of the chief white cook to correct this condition." [4]

Sanitation was another issue. In a May 29 report for the War Department, Shriver's successor, Nicholas L. Bican, noted that the "mess buildings lacked sufficient pantry area and good dish washing facilities," that the "plain wood table tops contained know (sic) holes and cracks," and that there were problems in the proper handling of garbage. "These conditions made for an unsanitary situation," he concluded. [5]

There were similar issues with the showers, sinks, and toilets. Each of the shower rooms had eight shower heads; however, the water temperature adjustment was "located in the heating room and was not accessible from the shower room." The sinks did not have hot water at all. In addition, the "slope of concrete floors [in the showers] toward drain points was not adequate for good drainage." [6]

Latrines were of the pit variety and unpartitioned. As Shriver wrote in a May 6 report, the latrines "present a sanitary hazard since they are very shallow, and have dirt floors." In an interview conducted a little more than a year after he was there, former inmate Hiroshi Sugasawara vividly recalled the latrines:

The latrines were nothing but eight or ten foot pits and 3/4 or 1/2 inch third grade pine with knot holes and knots dividing the men and women's latrines. We were just back to back. God, that was awful. After the first few days all the latrines began to smell. After about four weeks they were practically overflowing. The administration began digging new latrines ten feet away from the existing latrines. They were so crudely constructed and so strategically placed that with every shift of wind the stench could be smelled at all times. I think those were the most disgusting things in the center.

Some effort was made to improve the situation by installing flush toilets. However, in a June 1 report, Bican wrote that the "plan to construct flush type latrines was abandoned for lack of disposal facilities." [7]

Camp Population

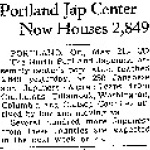

Marysville's population was a fairly homogeneous one that arrived in two main groups. In mid-May, Japanese Americans from western Placer County including the towns of Loomis, Roseville, and Rocklin were forcibly removed through Civilian Exclusion Orders #47 and 48. Consisting of about 1,500 people, this group arrived at Marysville between May 11 and May 14. They were preceded by a group of an "advance medical unit" of fifty-two people (including family members) who had arrived a few days prior. About two weeks later, the second large group, from an area south of Sacramento that included part of the Florin, Oak Park, Elk Grove, and Riverside communities, arrived numbering about 900. Both groups were largely rural and both were relatively close to Marysville, mostly within sixty miles. The first group was mostly assigned to barracks in Blocks 1 to 3, while the latter went to Blocks 4 to 6. A large and cohesive farming community prior to the war, Florin was among the communities split by the forced removal, with segments of that community going to Fresno Assembly Center and to Manzanar as well as to Marysville. There were no reports of friction between the two major groups at Marysville. [8]

| Exclusion Order # | Deadline | Location | Number |

| 47 | May 14 | West Placer County | 885 |

| 48 | May 14 | East Placer County | 644 |

| 93 | May 30 | South Sacramento County; Florin | 902 |

Source: John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 363–66. Exclusion orders with fewer than twenty inductees not listed. Deadline dates come from the actual exclusion order posters, which can be found in The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley, http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b016b01_0001_1.pdf and http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b016b01_0001_2.pdf .

| Arrival Date | Number |

| May 8 | 58 |

| May 11 | 165 |

| May 13 | 791 |

| May 14 | 528 |

| May 15 | 3 |

| May 21 | 1 |

| May 23 | 1 |

| May 27 | 418 |

Source: Nicholas L. Bican, Report to R. L. Nicholson, May 29, 1942, p. 1, 1.144 Report-Center Status for War Department, 1.1 Center Manager's File, 1 General Correspondence File, WCCA Marysville, Reel 13-L, NARA San Bruno. Note that induction of Sacramento County group was ongoing as this report was being completed, so this chart does not include all of this group.

Given the short time the camp was in operation and its relatively small population, there were only four births and one death in the camp. The births included Beverly Maeda, May 23; Norman Yoshiyuki Moriguchi, May 29; Caroline Tatsuko Kodakari, June 8; and Tomiko Morita, June 15. The lone death noted was that of Kenjuro Yokoi of Florin, who died on May 31 at the camp hospital at age 55.

[9]

Essentially all of the population at Marysville was subsequently sent to the Tule Lake, California, concentration camp at the end of June. [10]

| Departure Date | Number |

| June 24 | 520 |

| June 25 | 499 |

| June 26 | 488 |

| June 27 | 490 |

| June 28 | 397 |

Source: John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 282–84.

In a June 15 report, Bican wrote that the last arrivals—meaning the Florin group—would be the first to go to Tule Lake. Inmates first boarded Gibson Line busses to the nearby Pearson Railroad Siding, where which they were transported by train the approximately 260 miles to Tule Lake.

[11]

Staffing

In its short lifespan, Marysville had two managers. Paul D. Shriver arrived at the site on April 6 and oversaw the opening of the camp and the first large group of arrivals. He was succeeded by Nicholas L. Bican on May 19, who remained manager for the rest of the camp's life. After Marysville closed, he moved on to become the manager of the Portland Assembly Center in July. A University of California educated civil and mechanical engineer, Bican's salary at Marysville was $3,600 a year. [12]

As was true of the other assembly centers, most of the administrative staff came from the ranks of the WPA. Bican came from the WPA Division of Operations, Area 3, Sacramento, as did several other staffers, including Supervisor of Supplies Henry E. Deni, maintenance and construction heads John R. Miller and Ralph Temby, and Timekeeping Supervisor Milton B. Webber. Store Manager Charles E. Mapother came from the WPA Finance Division, Area 3, Sacramento. Assistant Manager William Dougherty and Supervisor of Feeding the Housing William Thatcher came from WPA units in Seattle; while Supervisor of Finance and Records Harry Z. Oleson came from the WPA Supply Section, Butte, Montana; and Service Director Leo Randall from the WPA Recreation Department, Yuba-Sutter Counties. Other Marysville staffers were local hires. [13]

Institutions/Camp Life

Community Government

Despite the camp's short lifespan, administrators attempted to institute what was effectively an elected advisory board. Soon after the arrival of the first group, elections were held in each block to choose male and female block monitors. This continued as later blocks were filled. On June 4, the twelve block monitors met and elected three councilmen who would "represent the Center in meetings with Management." In his June 23 report, Bican claimed that the twelve monitors met daily with the councilmen to go over issues raised in each block; the councilmen then met every afternoon with camp administrators. [14]

Bican went on to write that the "internal self government was extremely cooperative in organizing mess crews, maintenance crews and work crews," and that they helped solve block level problems, citing the institution of a system to stagger use of irons and hotplates so as to prevent electrical problems in barracks. "Experience has shown that these people are aggressive and tend to assume administrative functions beyond the policies set by management," Bican went on to warn. "A constant pressure is required to hold them within the established boundaries." [15]

Block Monitors:

Block #1: Clifford Yamada; Mrs. Geo. Kawahata

Block #2: Shig Yamane; Mrs. H. R. Yamasaki

Block #3: S. Yamada; Mrs. J. Y. Chikuda

Block #4: Chas. Nitta; Mrs. Fred Sakamoto

Block #5: Coffee H. Oshima; Joyce Kawamoto

Block #6: Harry M. Yokoyama; Mrs. Harvey Itogawa

Councilmen: S. Kubo, Cal Sakamoto, and K. Hamatani

[16]

Education

Given the short life span of the camp, there was only a preschool (enrollment of sixty as of May 29) and no summer school for elementary, middle school or high school age youth. [17]

Medical Facilities

Two barracks buildings were set aside for the camp hospital. One had TB, communicable disease and pediatric wards, while the other had medical, surgical, and obstetrics wards. According to the May 29 report, there was a daily average of thirty-five outpatients and fourteen in-patients, along with eight dental patients. In his various reports, Bican cited "numerous and difficult" problems with medical care, most centering on a shortage of supplies and equipment and a shortage of medical staff. The head physician was Dr. Masa Harada, an Issei born in 1899. [18]

Library

The camp library was in the Information Building and, as of May 29, offered only magazines for circulation. The space was furnished by benches and tables made by inmates and was open from 9 am to noon, 1 to 4 pm, and 6 to 8 pm. The Marysville City Library lent date stamps and pads, files, cards and about 400 magazines and 322 books, though the books had yet to be displayed due to lack of space. Flora Terada managed the library. [19]

Newspaper

Four weekly issues of the ArboGram were published starting from May 23, each running four pages. The name was "chosen by popular vote" after the first issue. The paper was mimeographed on a loaned machine; the newspaper office in the administration building was furnished with homemade furniture. [20]

In a 1943 interview, news editor Hiroshi Sugasawara described the staff refusing to put out a final issue as ordered by Leo Randall, who supervised the staff. Because it was censored, the staff "couldn't present any controversial subjects whatsoever." He went on to call it "just a tabloid full of hot air" and "a god damn gossip column and a voice of the administration," concluding that "It wasn't a newspaper by a long shot." [21]

ArboGram staff:

Editor: Bryan Mayeda

Managing editor: Hiro Uratsu

News editor: Hiro Sugasawara

Co-editor: Hiro Kashiwagi

Recreation editor: Chuck Hayashida

Women's editor: Meta Kageta

Art editor: Kats Morishige

[22]

Religion

A barrack was set aside for church activities (shared by an information center), and inmates built benches that could seat 100. As of May 29, there were four regular church groups: a Christian service for children (about 60 participants); a Christian service for adults (70); a young people's Fellowship Hour (90); and a Buddhist service (150). Camp manager Bican estimated that there were three times as many Buddhists as Christians in the camp. Christian services were led by Rev. S. Kawashima; Buddhist services by Rev. K. Iwao. [23]

Recreation

As with other programs, the camp's short lifespan meant relatively limited organized recreational activities. Four barracks were set aside for recreation, educational, and religious activities; these were equipped with donations from "[e]vacuee church groups, individuals, and Yuba County Junior College" and included a piano, PA system, movie projector, sports equipment, and preschool equipment. [24]

Among the activities listed in Bican's May 29 report were weekly dances which drew an average of 300, a glee club, athletics (180); arts and crafts (30); and traditional Japanese "[d]ramatics and amateur" (350 twice weekly). There was also a Boy Scout troupe of about twenty-five, though they struggled with a "lack of projects or materials to work with." [25]

Store/Canteen

The camp store opened on May 15. Located in a barrack building that it shared with the camp post office, it was open from 9 to 4 daily. Nine inmates, including an inmate manager, staffed the store, under white store manager Charles E. Mapother. The store closed on June 20. Total sales for the store were $6,015. [26]

Visitors

Visitors were allowed on certain days at a visitors' hall. Neither the camp newspaper or the various reports filed by the administrative staff include any additional information on this topic. [27]

Other

The camp Fire Department had a chief and two assistants, all of whom were white, one of whom was on duty at all times. They were augmented by three inmate firemen on each shift. "Volunteers" drawn from mess crews made up the rest of the crew.

The Post Office opened on May 13 and was staffed by one U.S. Postal Service employee as the clerk-in-charge, along with inmate workers. It shared a barrack with the camp store. [28]

Chronology

May 1

John DeWitt

,

Karl Bendetsen

and others from WCCA office inspect the camp, making suggestions for improvements

May 8

First "volunteers" arrive.

May 14

Canteen opens.

May 19

Library opens.

May 23

First issue of the

ArboGram

issued.

May 24

First Visitors Day held from 10 am to 4 pm. Outsider visitors will meet inmates at the Administration building or the visitors hall.

May 24

First Buddhist service held, led by Rev. K. Iwao as well as first meeting of Christian Young People's church with a sermon delivered by Sam Takagishi.

May 25

Graduation ceremony held for 36 1942 graduates of Placer Union High School and 9 of Placer Junior College. Placer Union Principal Ernest Certel speaks at the ceremony.

June 2

Three-person council elected at block monitor's meeting; the three are Cal Sakamoto, K. Hamatani, and S. Kubo.

June 24

First group leaves for Tule Lake.

June 28

Last inmates leave.

Quotes

"It was really awful. I think in many ways, that was the worst part of camp experience: the assembly center experience, because everything was so temporary. And we had to line up all the time for food and line up, and line up for the latrine -- [laughs] -- and it's terrible."

Hiroshi Kashiwagi, 1992

[29]

"And I still remember that, the Arboga assembly center, it was next to a slough, and it was in the springtime, boy, you turned that light on, about forty-five minutes, there was so much bugs in there, you couldn't even see the light bulb."

Taketora Jim Tanaka, 2008

[30]

"Though hardly stylish at the time, many women and girls wore pants and slacks out of sheer necessity to protect themselves from the insects. But angry, unsightly welts on legs, arms, necks, even faces were not uncommon."

"What was most outrageous was going to the latrine: a public outhouse with accommodations for eight or eight holes in a line without partitions between them. How disconcerting it was, sitting there cheek by jowl, this necessary and what should have been a regular and fairly pleasurable function."

Hiroshi Kashiwagi, 2005

[31]

"I was looking forward to the day we would move out of Walerga. It was too small and crowded. To see the field and the dirtiness of the Japanese people was really disgusting. Eating sloppily in the messhall, and girls dressed so sloppily. I just didn't like the whole atmosphere. The climate wasn't so good either—swamp, mosquitoes, bugs, hot sweltering humid heat."

"It was hot as hell in there in May and June. Were in camp for about five weeks which were in the hottest period. Gnats were flying all over the place. The girls were ugly because their legs and arms were bitten by them. There were millions of mosquitoes."

Hiroshi Sugasawara, 1943

[32]

Aftermath

After the camp's closing, "[m]ost of the property from this Center" was shipped to the Gila River WRA concentration camp. [33]

Marysville Assembly Center was one of the twelve California temporary detention centers to share California Historical Landmark #934, so named in 1980. In 2009, the "Arboga Assembly Center Project" received a $5,000 grant from the Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program. In February, 2010, an exhibition focusing on the Arboga Assembly Center titled "Day of Remembrance: The Japanese American Internment Experience" was displayed at the Yuba College library. [34]

In 2019, the Yuba Sutter Arts & Culture received a $30,000 grant from the California Civil Liberties Public Education Program for a memorial at the site. The memorial park, consisting of a historic plaque that the Yuba County JACL had purchased in 2010, three metal sculptures in the shape of silhouettes of the barracks, and interpretive panels, was completed in February 2021 The memorial was designed by Stuart Gilchrist, and the sculptures made by Dan Turner. A re-dedication ceremony was held at the site on October 22, 2022. The memorial park is located on the north side of Broadway Street about a quarter of a mile east of Feather River Blvd. [35]

Notable Alumni

Emerick Ishikawa, Olympic weightlifter

Hiroshi Kashiwagi, playwright and poet

For More Information

Burton, Jeffery F., Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord, and Richard W. Lord. Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites . Western Archeological and Conservation Center, National Park Service, 1999, 2000. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002. The Marysville section of 2000 version accessible online at http://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/anthropology74/ce16b.htm .

The Road Not Forgotten: The Journey of Japanese Descendants in Butte, Colusa, Sutter and Yuba Counties (1889–1995) . Sacramento, California: Marysville Chapter, Japanese American Citizens League, 1995.

Footnotes

- ↑ WCCA Press Release, Mar. 28, 1942, John M. Flaherty Collection of Japanese Internment Records, MSS-2006-05-02, San José State University Library, Special Collections & Archives; Jeffery F. Burton, et al., Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002), 353–55; Nicholas L. Bican, Report to R. L. Nicholson, May 29, 1942, p. 1, 1.144 Report-Center Status for War Department, 1.1 Center Manager's File, 1 General Correspondence File, WCCA Marysville, Reel 13-L, NARA San Bruno; Hiroshi Kashiwagi interview with Chizu Omori and Emiko Omori, Segment 2, San Francisco, Oct. 1, 1992, Emiko and Chizuko Omori Collection, Densho Digital Archive, http://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1002/ddr-densho-1002-4-transcript-97a8966bd4.htm ; Richard M. Murakami interview by Larisa Proulx, Segment 5, Los Angeles, Nov. 19, 2014, Manzanar National Historic Site Collection, Densho Digital Archive, http://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-manz-1/ddr-manz-1-161-transcript-36859a3dbd.htm ; Taketora Jim Tanaka interview by Kirk Peterson, Segment 10, Sacramento, California, Oct. 19, 2008, Manzanar National Historic Site Collection, Densho Digital Repository, http://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-manz-1/ddr-manz-1-50-transcript-9ce84088ef.htm ; Hiroshi Kashiwagi, Swimming in the American: A Memoir and Selected Writings (San Mateo, Calif.: Asian American Curriculum Project, 2005), 81.

- ↑ ArboGram , May 23 and June 6, 1942, 4; 1.123 Fire Protection System Map, 1.1 Center Manager's File, 1 General Correspondence File, WCCA Marysville, Reel 13-L, NARA San Bruno; "Housing and Feeding Division" section of Bican, May 29, 1942 report; Paul D. Shriver, Report on Fire Protection System, May 14, 1942, 1.148 Reports Narrative, 1.1 Center Manager's File, 1 General Correspondence File, WCCA Marysville, Reel 13-L, NARA San Bruno; Memo, Nicholas L. Bican to All Evacuees, June 6, 1942, 1.128 Instructions—From Manager to Evacuees, 1.1 Center Manager's File, 1 General Correspondence File, WCCA Marysville, Reel 13-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Paul D. Shriver, Narrative Reports Nos. 5 and 7, May 9 and 18, 1942, 1.148 Reports Narrative, 1.1 Center Manager's File, 1 General Correspondence File, WCCA Marysville, Reel 13-L, NARA San Bruno; Letter, Paul D. Shriver to H. L. Nicholson, Apr. 26, 1942, 1.148 Reports Narrative, 1.1 Center Manager's File, 1 General Correspondence File, WCCA Marysville, Reel 13-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ "Housing and Feeding Division" section of Bican, May 29, 1942 report; Paul D. Shriver, Narrative Reports Nos. 7 and 8, May 18 and 19, 1942, 1.148 Reports Narrative, 1.1 Center Manager's File, 1 General Correspondence File, WCCA Marysville, Reel 13-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Bican, May 29, 1942 report, 1.

- ↑ Bican, May 29, 1942 report, 1, 10.

- ↑ Paul D. Shriver, Narrative Reports Nos. 4, and 7, May 6 and 18, 1942, and Nicholas L. Bican, Narrative Report No. 9, June 1, 1942, 1.148 Reports Narrative, 1.1 Center Manager's File, 1 General Correspondence File, WCCA Marysville, Reel 13-L, NARA San Bruno; Hiroshi Sugasawara, second interview with Tamotsu Shibutani, Oct, 25, 1943, p. 5, The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder T1.9931, http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b284t01_9931.pdf .

- ↑ John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 227, 363–66; Bican, May 29, 1942 report, 3; Paul D. Shriver, Narrative Reports Nos. 5 and 6, May 9 and 13, 1942, 1.148 Reports Narrative, 1.1 Center Manager's File, 1 General Correspondence File, WCCA Marysville, Reel 13-L, NARA San Bruno; Mary Tsukamoto and Elizabeth Pinkerton, We the People: A Story of Internment in America (San Jose: Laguna Publishers, 1987), 115.

- ↑ 3.54 Roster No. 10 and 3.55 Roster No. 11, Deaths Within Center, 3.5 Rosters, and Other Records of Departure from Center, 3. Personnel Records: Evacuee, WCCA Marysville, Reel 15-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Dewitt, Final Report , 282.

- ↑ Nicholas L. Bican, Narrative Report No. 10, June 15, 1942, 1.148 Reports Narrative, 1.1 Center Manager's File, 1 General Correspondence File, WCCA Marysville, Reel 13-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Bican, May 29, 1942 report, 1; Civilian Personnel Attached to Marysville Assembly Center as of May 27, 1942, and their Functional Activities, 2.16 Correspondence & Instructions Arranged Chronologically, 2.1 Appointment and Assignment Records, 2. Personnel Records, Caucasian, WCCA Marysville, Reel 14-L, NARA San Bruno; Portland Evacuazette , July 7, 1942, 2.

- ↑ Civilian Personnel Attached to Marysville Assembly Center as of May 5th and May 27th, 1942, and their Functional Activities, 2.16 Correspondence & Instructions Arranged Chronologically, 2.1 Appointment and Assignment Records, 2. Personnel Records, Caucasian, WCCA Marysville, Reel 14-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Nicholas L. Bican, Narrative Report No. 11, June 23, 1942, 1.148 Reports Narrative, 1.1 Center Manager's File, 1 General Correspondence File, WCCA Marysville, Reel 13-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Bican, Narrative Report No. 11, June 23, 1942.

- ↑ Bican, Narrative Report No. 11, June 23, 1942.

- ↑ "Service Division, Narrative and Factual Report" section of Bican, May 29, 1942 report.

- ↑ Bican, May 29, 1942 report, 1, 5; "Service Division, Narrative and Factual Report" section of Bican, May 29, 1942 report; Bican, Narrative Report No. 9; ArboGram , May 23, 1942, 1; Topaz Final Authority Report, 26.

- ↑ "Service Division, Narrative and Factual Report" section of Bican, May 29, 1942 report; ArgoGram , May 23, 1942, 4.

- ↑ "Service Division, Narrative and Factual Report" section, Bican, May 29, 1942 report.

- ↑ Hiroshi Sugasawara interview, 4-5.

- ↑ Data taken from masthead of various issues of the ArgoGram .

- ↑ "Service Division, Narrative and Factual Report" section, Bican, May 29, 1942 report.

- ↑ "Service Division, Narrative and Factual Report" section, Bican, May 29, 1942 report.

- ↑ "Service Division, Narrative and Factual Report" section, Bican, May 29, 1942 report.

- ↑ "Service Division, Narrative and Factual Report" section, Bican, May 29, 1942 report; Harry I. Oleson, Final Store Report and cover letter, June 25, 1942, 9. Duplicates, All Series, WCCA Marysville, Reel 18-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ ArboGram , May 23, 1942, 1.

- ↑ "Service Division, Narrative and Factual Report" section, Bican, May 29, 1942 report.

- ↑ Hiroshi Kashiwagi interview, Segment 2

- ↑ Taketora Jim Tanaka Interview, Segment 10.

- ↑ Kashiwagi, Swimming in the American , 81, 83.

- ↑ "Life History—Hiroshi Sugasawara," by James Sakoda, p. 10, The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder T1.9931, http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b284t01_9931.pdf ; Hiroshi Sugasawara interview, 5. Though the camp is transcribed as "Walerga" in the first quote, it is clear from Sugasawara's biography that is talking about Arboga/Marysville.

- ↑ Nicholas L. Bican, Narrative Report No. 12, July 9, 1942, 1.148 Reports Narrative, 1.1 Center Manager's File, 1 General Correspondence File, WCCA Marysville, Reel 13-L, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Barbara Wyatt, ed., Japanese Americans in World War II: National Historic Landmarks Theme Study (Washington, D.C.: National Historic Landmarks Program, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2012), 111–12; Ashley Gebb, "'Mystery Camp' Brought into Light," Appeal-Democrat , Feb. 7, 2010, https://www.appeal-democrat.com/mystery-camp-brought-into-light/article_a6483040-0e4c-57f8-b4f5-4d89d4f1e4c2.html .

- ↑ Yuba Sutter Arts & Culture and Marysville Japanese American Citizens League, Virtual Day of Remembrance Event, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C-1EeHxgc8A ; Michael Hatamiya, "Marysville Assembly Center Memorial Site Installed," Nichi Bei Weekly , Sept. 30–Oct. 13, 2021, 4, 14; Michael Hatamiya, "Arboga Assembly Center Memorial Site Re-Dedicated in Yuba County," Nichi Bei Weekly , Oct. 27–Nov. 9, 2022, 5.

Last updated Oct. 27, 2022, 11:33 p.m..

Media

Media