Merced (detention facility)

This page is an update of the original Densho Encyclopedia article authored by Adrienne Iwata. See the shorter legacy version here .

| US Gov Name | Merced Assembly Center, California |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | Temporary Assembly Center |

| Administrative Agency | Wartime Civil Control Administration |

| Location | Merced, California (37.3000 lat, -120.4667 lng) |

| Date Opened | May 6, 1942 |

| Date Closed | September 15, 1942 |

| Population Description | Held people from the Northern California coast, west Sacramento Valley, and northern San Joaquin Valley, California. |

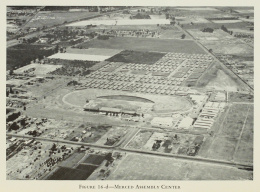

| General Description | Located in California's central San Joaquin Valley within the town of Merced at the county fairgrounds; the buildings were sited south of the fairgrounds proper. |

| Peak Population | 4,508 (1942-06-03) |

| Exit Destination | Granada |

| National Park Service Info | |

The Merced Assembly Center, built on the Merced County Fairgrounds property, was populated from May 6 to September 15, 1942, a total of 133 days, and had a peak population of 4,508, making it near the median among " assembly centers " in both categories. The inmates came mostly from rural areas and small towns in Central California as well as north coastal areas above San Francisco. They were housed in just under two hundred hastily built barracks east of the racetrack. As with other Central California assembly centers, inmates battled intense heat and insects as well the usual cramped quarters, lines, and lack of privacy. Essentially the entire population went to the Amache , Colorado, concentration camp in September. A memorial dedicated in 2010 stands at the site of the camp today.

Site History/Layout/Facilities

The Merced Assembly Center was built on the site of the Merced County Fairgrounds and several adjacent lots acquired from private parties in the southwestern portion of Merced. Most of the buildings—including all of the nearly two hundred barracks—were newly built east of the racetrack, with a handful of existing fair buildings south and west of the racetrack being used for administration purposes and as warehouses. This included the former exhibit building, a 125 x 80 foot structure that housed administrative offices as well as offices for the inmate council and newspaper. The residential area was divided into ten wards (essentially the same as " blocks " in other camps) that were assigned letters "A" through "J," each containing between eighteen and twenty-one barracks, a mess hall, washrooms, and toilets and holding roughly 450 people. A central area included the camp hospital, store, and post office. There was initially very limited space for recreation, but a reconfiguration of the camp boundaries after the first month led to the racetrack area and its infield being used for outdoor recreation. [1]

As with other camps in Central California, Merced inmates had to cope with extreme summer heat, mosquitoes and various other fauna, along with the usual lack of privacy, spotty food, and inadequate medical care. A barbed wire fence surrounded the camp with guard towers at the corners and intersections staffed by armed guards. [2]

The camp was built very quickly and out of substandard materials. As one inmate snidely wrote in a contemporaneous letter, "the contractors apparently employed anyone who could use a hammer and saw," resulting in "crudely built" buildings. Merced's first manager, Dean W. Miller, observed that the "lumber that was used in the camp construction... is of the very poorest grade, and in normal times wouldn't be considered for use in building construction." Miller added that construction had been hampered by heavy rains, leading to the streets being in "terrible condition" due to the "gumbo-clay" soil. [3]

The barracks were typical of those found in other assembly centers, measuring 20 x 100 and mostly subdivided into five "apartments" of varying sizes. Most had concrete floors, though some had wood. Internal partitions were made of 1/4" plywood that did not go all the way to the roof, allowing sound to travel throughout the building. The three foot square windows as well as doors that were sometimes too small for the doorways occasionally leaked, letting in rain and mud. Doors were initially not screened, though screens were added later. Because they were laid directly on the ground, dirt and various insects and rodents entered the units that had wood floors through the gaps between the boards. [4]

The mess halls in each ward were in buildings the same size as the residential barracks and had a capacity of about 160 inmates per meal, necessitating three shifts for each meal. One result of this system, according to a July external inspection, was that there was "little time to clean up between meals and this probably is responsible for the fact that the kitchens were not in better order." It also allowed some inmates to eat multiple meals at different mess halls. In early June, camp administrators introduced a system designed to prevent this by issuing colored tags to inmates that specified which mess hall they were to eat at and that also specified which shift they were assigned to. The mess halls were also hampered by a lack of cooking equipment early on, though this problem seems to have been alleviated by June. Weekly reports by the camp managers note the food cost per inmate of about 40¢ per person per day. [5]

The latrines were similar to other central valley camps, consisting of a long wooden bench with holes cut into it suspended over a galvanized trough. The "flushing" system consisted of a water tank at one end that would periodically empty, sending a stream of water through the trough. Whoever was sitting on the end learned that water would splash up as the water streamed through. There were no partitions either between the toilets or in the showers. There were four laundry buildings in various parts of the camp. [6]

Camp Population

The inmate population at Merced was relatively diverse, if mostly rural, consisting of four distinct groups. The largest was from rural Colusa and Yolo Counties, north and west of Sacramento, a group consisting of about 1,600 people. A slightly smaller group consisted of people from farming communities near Merced, including Modesto, Dos Palos, and the agricultural colonies founded by journalist Kyutaro Abiko , Livingston, Cressey, and Cortez. There were smaller groups from the north coastal areas above San Francisco, including Marin, Sonoma, and Napa Counties and from the agricultural communities of Walnut Grove and Courtland south of Sacramento. These populations arrived in a relatively short time frame in mid to late May. The population peaked shortly thereafter at 4,508 on June 3. There were twenty-one births and ten deaths in Merced's 133 day lifespan. [7]

| Exclusion Order # | Deadline | Location | Number |

| 50 | May 13 | Modesto, Turlock | 516 |

| 51 | May 13 | Merced County: Dos Palos, Livingston, Merced | 890 |

| 65 | May 17 | Marin, Sonoma, Napa Counties | 665 |

| 69 | May 18 | Colusa County: Yuba City, Marysville | 757 |

| 76 | May 19 | Yreka, Redding | 99 |

| 78 | May 21 | Yolo County | 858 |

| 94 | May 30 | Walnut Grove, Courtland | 476 |

Source: John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 363–66. Exclusion orders with fewer than fifty inductees not listed. Deadline dates come from the actual exclusion order posters, which can be found in The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley, http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b016b01_0001_1.pdf and http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b016b01_0001_2.pdf .

The mostly small town population initially "stuck with their own groups," recalled one inmate in a 1944 interview, adding that "gradually they began to mix much more as everyone was interested in making other friends as the experience was something new to them." She also observed that the many "country Nisei" at the camp began to branch out more, as they "gradually began to come to the dances even if their parents objected."

[8]

| Departure Date | Number |

| August 25 | 212 |

| September 1 | 557 |

| September 2 | 550 |

| September 3 | 556 |

| September 5 | 553 |

| September 7 | 527 |

| September 13 | 529 |

| September 14 | 527 |

| September 15 | 481 |

Source: John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 282–84.

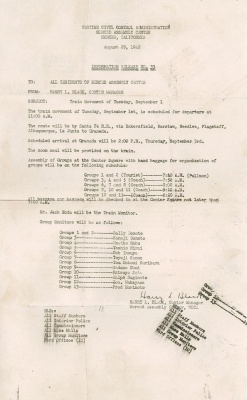

Essentially the entire population of Merced was transferred to the Amache, Colorado, concentration camp, where they would mix with the urbanites of west and south Los Angeles. The transfer began roughly three months after the arrivals, with a carefully curated advance group of 212 workers who would help set up the new camp; this group left Merced on August 25. The rest of the population went in groups of about 500 from September 1 to September 15. While the initial plan was to send out a group every day, the pace was slowed after three days when it turned out that Amache was not yet ready to induct inmates so quickly, as living quarters for them had not been completed. The pace slowed first to a group every other day, then a five-day break until the last three groups went out.

[9]

Staffing

Merced had two managers in its brief lifespan. The first was Dean W. Miller, who had been the state administrator for the WPA in Montana. Miller left Merced on June 8, after the entire camp population had arrived, to return to the WPA. Harry L. Black, who had been Miller's assistant for two weeks prior to his departure, took over as manager in what seemed to be a seamless transition. Black was a World War I veteran who had also come over from the WPA via Manzanar, where he had been the assistant camp manager. Black served as manager of Merced for the rest of its existence. Other key staffers included:

Supervisor of Education and Recreation: Richard E. Mitchell

Supervisor of Works and Maintenance: Bert Mankins

Supervisor of Mess and Lodging: Stephen Schramm

Service Director: E. A. Woodside; J. Mervin Kidwell

Chief of Police: W. H. Bachman

Fire Chief: Vern S. Stockholm

[10]

In addition to Miller and Black, much of the rest of the administrative staff came from the ranks of the WPA, something that was true for most of the other assembly centers as well. Service Director E. A. Woodside was the assistant director of employment for the WPA in California and had helped set up Manzanar , Tulare and Tanforan before coming to Merced. Woodside returned to the WPA and was replaced by Kidwell, another WPA staffer who had been the head of the service division at Manzanar, on July 17. Mitchell and Schramm also came from the ranks of the WPA. [11]

Institutions/Camp Life

Community Government

As at other assembly centers, there were both appointed and elected bodies of inmates that served in a purely advisory capacity to the center managers. Changing WCCA regulations on such bodies—first prohibiting Issei participation and then later abolishing the bodies entirely—affected their composition at Merced.

As the inmates flowed into the camp, the first manager Dean W. Miller began appointing both ward officers—a group of ten, one from each ward—as well as a "Council of five" commissioners. The plan was for the ward officers to eventually be replaced by elected representatives. The original ten ward representatives were

A: Masao W. Hoshino

B: Saburu Cujow

C: Tseneo Iwata

D: Sam Kuwahara

E: Henry Shimizu

F: George Otani

G: James Nakamura

H: George K. Matsumura

I: Yorio Aoki

J: Fred Arimoto

[12]

The five appointed commissioners were Dr. Masuichi Higaki, an Issei dentist from San Francisco; Jack Noda, a thirty-two year old Nisei produce grower and shipper from Denair and a Stockton JACL board member; F. T. Konno, an Issei farm cooperative manager from Livingston; Sam Kuwahara, a thirty-two-year-old Nisei manager of the Cortez Growers' Association; and Dr. Takashi Terami, an Issei language school teacher from Walnut Grove. According to second manager Harry L. Black's June 23 weekly report, the ten ward officers "met daily with the Center Manager." [13]

After the WCCA issued a directive prohibiting Issei from either voting or holding office in any self-government organization, the three Issei commissioners resigned. An election had been held on June 23 to elect new ward officers, but that election had to be invalidated, since Issei had been allowed to vote. A second election on June 29 resulted in the following ward officers, a man and a woman from each ward:

Ward A: Masao Hoshino, Yuki Tanaka

Ward B: Isaac Matsushige, Miye Yamasaki

Ward C: Buddy Iwata, Grace Narita

Ward D: Aki Yoshimura, Chiyo Furuno

Ward E: Henry Shimizu, Marie Kai

Ward F: George Otani, Dorothy Nakamura

Ward G: Mitsuo Kagehiro, Mona Hirooka

Ward H: George Matsumura, Mabel Furukawa

Ward I: Tokio Kawashima, Mitsuyo Okamoto

Ward J: Tim Sasabuchi, Mollie Wada

[14]

Buddy Iwata, a twenty-four-year-old Nisei from Turlock who was a 1939 Stanford graduate, was elected president of the ward council. [15]

Black also replaced the Issei commissioners with Nisei Walter S. Higuchi and Takashi Koga, both of whom were around forty and born in Hawai'i; Higuchi had been with Goodyear Rubber and was a member of Los Angeles JACL, while Koga was from Petaluma. Noda was named chief commissioner. [16]

When the WCCA issued new regulations banning inmate self-government at the beginning of August, Black asked for and received resignations of all twenty ward representatives. The commissioners were allowed to continue to serve in an advisory role for the rest of the life of the camp. [17]

Education

Given its relatively long life, inmates and administrators at Merced ran a non-compulsory summer school for elementary, middle, and high school children, as well as a series of adult classes. The schools ran from June 10 to August 21. Takashi Terami headed the education department that included twenty inmate teachers, all of whom had at least two years of college and half of whom had college degrees. [18]

The schools faced many obstacles, the most significant likely being the lack of dedicated space. As a result, classes were held in vacant "apartments," in the recreation barracks, and even the bleachers and grandstand; in some cases, classes had to be moved multiple times, as new inmates moved into the apartment classrooms. Additionally, there were no desks, blackboards or books initially, and some students had to sit on the floors. Nonetheless, the enrollment numbered 330 elementary students and 450 middle and high school students. [19]

In addition to the children's program, there were also adult classes, in particular English classes aimed at Issei that drew about 100, along with classes "ranging from bookkeeping and shorthand to architecture [and], a lecture course in chemistry." As at other camps, there was also a graduation ceremony for students who missed their actual graduation due to their incarceration. [20]

Medical Facilities

The camp hospital occupied three barracks in the center of the camp. Services included a dental clinic equipped with a homemade dental chair adapted from a barber chair, a pharmacy, doctor's offices, hospital wards, and a dieticians unit. The first head physician was Dr. Walter Iriki. In July, he was transferred to Puyallup with his family. On July 25, new head physician Dr. H. O'konogi arrived from Pinedale upon that camp's closing and remained in that position for the duration. [21]

Library

The camp library was located in Ward B-1 and opened on June 19. Efforts to establish the library as a branch of the Merced County Public Library proved unsuccessful, though the library did donate some material to the camp. Most of the collection came from the inmates. Led by head librarian Mabel Andow, the camp library averaged 150 visitors a day, and books were allowed to be checked out overnight. [22]

Newspaper

Inmates produced twenty-one issues of the camp newspaper titled the Mercedian , which debuted on June 9. Two issues a week that were either four or six pages long appeared for most of its run. A final thirty-seven page "Souvenir Edition" appeared on August 29. As with other assembly center newspapers, the Mercedian provided basic news about the camp, served as a vehicle for conveying messages from the administration, and highlighted sports and recreation, while publishing under the watchful eye of camp managers. The relatively stable staff was led by managing editor Oski Taniwaki, a thirty-eight year old Issei man from Walnut Grove who had been the English editor of the Shin Sekai , and editor Tsugime Akaki a twenty-two year old Nisei woman from Modesto. Other regular contributors included Suyeo Sako (recreation); Kanemi Ono, Mac Yamaguchi, and Walt Fuchigami (sports); and Lily Shoji and Lorraine Yamaguchi (women), along with artist Jack Ito. [23]

Religion

There were both Buddhist and Christian services at Merced, along with both Buddhist and Christian youth groups. [24]

Recreation

While Merced would come to have an extensive recreational program centered around baseball and sumo, there was little for the first month due to a lack of space and facilities. The racetrack infield area and bleachers/grandstand were initially on the outside of the barbed wire fence as part of the MP's section. Camp management lobbied for the use of that space with the WCCA and eventually won out. In his May 26 report, Miller wrote, "We are starting to fence our new recreation ground, and everyone in the Center is very much pleased over this with the exception of the Military Police." Once the fence had been moved, inmate labor prepared baseball diamonds and a sumo ring, among other facilities. [25]

Due to strong prewar traditions, baseball and sumo both proved popular. The baseball league preserved prewar community identities and with some existing community teams able to reform largely intact. The baseball games, along with large sumo tournaments on July 4 and August 16 drew large crowds. Other sports included basketball, badminton, football and ping pong. [26]

Other popular recreational activities included regular talent shows, dances, and popular craft shows. Seventeen-year old trombonist Paul Higaki—who later played professionally in vibraphonist Lionel Hampton's band after the war—organized a twelve-piece band named the Stardusters in June that featured the vocals of Sumi Kawamura that played at many of the dances and shows. There were also Girl Scouts and Boy Scouts. [27]

Store/Canteen

The camp store was located in the center of the camp opposite the hospital and adjacent to the post office and police station. It later moved into expanded quarters on July 25. The store sold items including cold drinks, candy and other sweets, along with cosmetics and notions. After the renovation, daily sales went from $375 in June to about $1,000 by August. [28]

A barber shop with three barbers opened on July 25 in part of the adjacent laundry building. Haircuts cost 20¢. [29]

Visitors

A visitors' room was located at the west end of the administration building. Visiting hours were from 8 to 5. There were 805 total visitors as of July 3. [30]

Other

During an April 25 visit, Western Defense Command head General John DeWitt expressed concern about fire dangers at Merced and instructed the administration to put a fire extinguisher in every apartment. (Such fire extinguishers did not appear.) The lack of fire equipment and the fire danger was a regular theme of manager weekly reports through June, when the camp finally received minimally adequate equipment. [31]

The wage scale for inmates was the standard $16/$12/$8 per month scale for professional/skilled/unskilled work. [32]

Chronology

April 25

Gen. DeWitt and staff visit the camp.

May 6

The first family of Japanese American inmates arrives at Merced. Larger groups would begin to arrive the following week.

May 12

Opening of hospital.

May 30

Four hundred attend the first dance at Merced, held in the administration building.

June 3

Merced's population peaks at 4,508.

June 4

A group of 65 (56 men, seven women, two children) leave to do sugar beet work in Montana.

June 5

The first birth at Merced, a girl, to Mrs. Haruko Agatsuma.

June 8

Harry L. Black replaces Dean W. Miller as the camp manager of Merced.

June 9

First issue of the

Mercedian

.

June 19

Library opens.

June 24

Election is held but results are declared void the next day due to a change in WCCA policy banning Issei from voting.

June 29

The "second and revised" election takes place, sans Issei voters.

July 2

Graduation ceremony for 265 graduates of elementary, high school, and junior college held at the grandstand. Keynote speech by Dr. Hubert Phillips, dean of the lower division and professor of social science at Fresno State College.

July 4

July 4 program included the induction of the newly elected ward representatives, a parade, an all-star baseball game, and a sumo tournament.

July 10

Walter Bolderston and Henry Tyler of the

National Japanese American Student Relocation Council

come to Merced to speak to prospective students about leaving to attend college.

July 16

Bon Odori pageant held at Merced. 400 kimono-clad dancers take part.

July 15

Announcement that Merced inmates will be sent to Amache, Colorado.

July 22

Red Cross fact-finding committee visits the camp.

July 25

Opening of barber shop.

July 27

First Town Hall Forum on the topic "What Should Be Our Attitude Toward Evacuation?" held in the administration building. Speakers include Harry L. Black, Richard Mitchell, and J. M. Kidwell, moderated by Isaac Matsushige. About 200 attended, most of them Nisei.

Aug. 12

Second Town Hall Forum on the topic "Post-War Dissemination of Japanese" includes a panel of Takashi Moriuchi, James Nakamura, Mas Miyashita, and Fred Hashimoto.

Aug. 21

The last regular issue of the

Mercedian

.

August 25

First advance group of 212 inmates leave for Amache.

Aug. 29

Final "Souvenir Edition" of the

Mercedian

.

September 15

Final inmates leave for Amache, and the camp closes.

Quotes

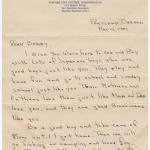

"When we first saw our living quarters we were so sick we couldn't, eat, walk, or talk. We couldn't even cry till later."

"... but gee—you should see the —er—latrines. There is absolutely no privacy or sanitation—10 seats lined up (hard, fresh-sawed, un-sandpapered wood) and it flushes automatically about every 15 minutes."

Ruth Ihara, 1942

[33]

"I had an awful reaction to it when I saw all the tar paper barracks. I was so depressed and I was amazed at the lack of privacy. I certainly was not glad to get there and I was disgusted to have to live in such a place."

Violet Kunimoto Kimoto, 1944

[34]

"In the prevailing hot weather our rooms are just like ovens. There is no escape because there isn't any artificial or natural shade except for a few scattered trees in inconvenient places."

"We have been sick too often and too long, due to the crowded inadequate housing, bad food—low grade—little variety—too much of it canned and spoiled, pitifully inadequate medical facilities (only 3 doctors and a very limited supply of drugs and equipment), and the weather."

Harry Fujita, 1942

[35]

Aftermath

While the Merced County Fairgrounds still exists, nothing of the former assembly center still exists, with the site now part of a parking lot at the current fairgrounds site. [36]

The Merced Assembly Center was one of twelve California sites to share California Landmark #934 in 1980. In 1982, The Livingston-Merced JACL led an effort to install a plaque at the site. [37]

In 2008, local JACL chapters formed a Commemorative Committee at the behest of Congressman Dennis Cardoza to work towards building a memorial at the site. The board of the fairground allotted a 600 square foot site in a high traffic area for the memorial. On February 20, 2010, the memorial, titled "To Remember Is to Honor," was dedicated. The memorial includes a bronze statue sculpted by Dale Smith of a girl sitting on a pile of suitcases along with interpretive panels and that include the names of inmates held at Merced. The Commemorative Committee also produced a documentary film titled The Merced Assembly Center: Injustice Immortalized in 2012. [38]

Notable Alumni

Paul Higaki, musician

Emiko Nakano

, artist

Koichi Nomiyama

, painter

Pat Suzuki

, singer and actress

For More Information

Hirano, Kiyo. Enemy Alien . George Hirano, Yuri Kageyama, trans. San Francisco: Japantown Art and Media Workshop, 1984.

Matsumoto, Valerie J. Farming the Home Place: A Japanese American Community in California, 1919-1982 . Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1993.

Merced Assembly Center video. Japanese American Memorial Pilgrimages, 2018.

The Merced Assembly Center: Injustice Immortalized . Video produced by the Merced Assembly Center Commemorative Committee, 2012. 53 minutes. [Streaming at PBS website, https://www.pbs.org/video/byyou-exploration-merced-assembly-center-memorial/ ]

Footnotes

- ↑ Jeffery F. Burton, et al., Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002), 356–58; WCCA Press Release, Mar. 28, 1942, John M. Flaherty Collection of Japanese Internment Records, MSS-2006-05-02, San José State University Library, Special Collections & Archives; Letter, Harry Fujita to H. A. Strong, Aug. 9, 1942, Gaye LeBaron Collection, Sonoma State University Library, California State University Japanese American Digitization Project, accessed on Mar. 2, 2020 at https://cdm16855.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16855coll4/id/579 ; John Hirohata, "Grapevine Scribe Air Mails Merced Story," Fresno Grapevine , Sept. 19, 1, 4; Mercedian , June 9, 1942, 1, 8 and June 19, 1942, 6; Dean W. Miller, Weekly Reports, May 19 and 26, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno; Harry L. Black, Weekly Reports, June 9, 16, and 23, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Hirohata, "Grapevine Scribe,"; Letter, Fujita to Strong, Aug. 9, 1942; Kiyo Hirano, Enemy Alien (translated by George Hirano and Yuri Kageyama, San Francisco: Japantown Art and Media Workshop, 1984), 7–8; Dean W. Miller, Semi-Weekly Report, May 9, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Letter, Fujita to Strong, Aug. 9, 1942; Dean W. Miller, Semi-Weekly Report, Apr. 26, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Valerie J. Matsumoto, Farming the Home Place: A Japanese American Community in California, 1919-1982 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993), 104; Letter, Fujita to Strong, Aug. 9, 1942; Hirano, Enemy Alien , 7–8; Letter, Ruth Ihara to "Barbara," May 13, 1942, The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder B12.48, http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_box025b12_0048.pdf ; Dean W. Miller, Semi-Weekly Report, May 9, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno; Harry L. Black, Weekly Report, July 28, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Letter, Fujita to Strong, Aug. 9, 1942; Mary I. Barber and J. W. Brearley, memo to Lieutenant Colonel Ira K. Evans, Western Defense Command, July 21, 1942, in Roger Daniels, ed., American Concentration Camps: A Documentary History of the Relocation and Incarceration of Japanese Americans, 1942-1945 , Vol. 6 (New York: Garland Publishing, 1989); Dean W. Miller, Weekly Report, May 26, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno; Mercedian, June 9, 1942, 2; Harry L. Black, Weekly Reports, June 9 and 16, and July 21, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Matsumoto, Farming the Home Place , 104–05; Hirano, Enemy Alien , 8; Letter, Ihara to "Barbara," May 13, 1942; Mercedian, June 9, 1942, 8 and June 19, 1942, 6.

- ↑ John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 202, 227, 363–66; Matsumoto, Farming the Home Place , 104; Gilbert Tanji interview by Sherman Kishi, July 7, 1999, p. 8, JACL-CCDC Japanese American Oral History Collection, California State University, Fresno, California State University Japanese American Digitization Project, accessed on Mar. 2, 2020 at https://cdm16855.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16855coll4/id/11225 ; Bob Fuchigami interview by Richard Potashin, Segment 16, May 14, 2008, Denver, Colorado, Manzanar National Historic Site Collection, Densho Digital Repository, http://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-manz-1/ddr-manz-1-28-transcript-a7ebc87379.htm .

- ↑ Violet Kunimoto Kimoto interview by Charles Kikuchi, 1944, pp. 57–58, The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder T1.983, accessed on Feb. 2, 2020 at http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b283t01_0983.pdf

- ↑ Dewitt, Final Report , 283; Harry L. Black, Weekly Reports, August 18 and Sept 7, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno; Mercedian , Aug. 21, 1942, 1.

- ↑ Mercedian , June 9, 1, 2, 4 and June 19, 1, 3; Harry L. Black, Weekly Report, June 9, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Mercedian , June 23, 1942, 3, July 7, 1942, 3, July 14, 1942, 3, and July 21, 1942, 3; Harry L. Black, Weekly Report, July 21, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Memos, Dean W. Miller to Masao W. Hoshino, May 12 1942 and Dean W. Miller to Masuichi Higuchi, May 15 1942, Civic Central Government, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78; Mercedian , June 9, 1942, 4.

- ↑ Harry L. Black, Weekly Reports, June 16 and 23, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno; Mercedian , June 19, 1942, 1, July 10, 1942, 3, and July 21, 1942, 3.

- ↑ Letters, Harry L. Black to Masuichi Higaki, Harry L. Black to Takashi Terami, Harry L. Black to Frank T. Konno, all June 29, 1942, Civic Central Government, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno; Harry L. Black, Weekly Report, July 7, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno; Mercedian, June 30, 1942, 1 and Aug. 29, 1942, 5; Memo, Harry L. Black, July 3, 1942, Civic Central Government, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Mercedian , July 31, 1942, 3.

- ↑ Letter, Harry L. Black to Emil Sandquist, July 21, 1942, Civic Central Government, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Harry L. Black, Weekly Reports, August 11 and 18, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ "Education Department" manuscript, pp. 2, 5, Harold S. Jacoby Nisei Collection, University of the Pacific, accessed on Mar. 2, 2020 at https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/kt2q2n991r/ .

- ↑ "Education Department" manuscript, 2, 6; Harry L. Black, Weekly Reports, June 9 and 16, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ "Education Department" manuscript, 4; Harry L. Black, Weekly Report, June 23, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Mercedian , June 9, 1942, 8, June 19, 1942, 6, and Aug. 18, 1942, 1, 3; Harry L. Black, Weekly Reports, July 14 and 28, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Mercedian , June 9, 1942, 3, June 23, 1942, 3, July 10, 4, and Aug. 11, 1942, 4; Harry L. Black, Weekly Report, June 23, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ All information in this section taken from various issues of the Mercedian .

- ↑ Matsumoto, Farming the Home Place , 110.

- ↑ Dean W. Miller, Weekly Reports, May 19 and 26, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno; Harry L. Black, Weekly Report, June 9, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Gilbert Tanji interview, 8; Bob Fuchigami interview, Segment 16; Harry L. Black, Weekly Report, August 18, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno; various issues of the Mercedian .

- ↑ Harry L. Black, Weekly Report, August 18, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno; George Yoshida, Reminiscing in Swingtime: Japanese Americans in American Popular Music: 1925-1960 (San Francisco: National Japanese American Historical Society, 1997), 168, 214–16; Letter, Fujita to Strong, Aug. 9, 1942.

- ↑ Harry L. Black, Weekly Reports, July 14 and 28, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno; Mercedian , Aug. 29, 1942, 8.

- ↑ Mercedian , July 10, 1942, 1; Harry L. Black, Weekly Report, July 28, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Mercedian , June 9, 1942, 6 and July 3, 1942, 3.

- ↑ Dean W. Miller, Semi-Weekly Report, Apr. 26, 1942, Reports – Weekly Narrative, Center Manager, A. Merced Center Manager, 1. General Correspondence File, Merced Assembly Center, Reel 78, NARA San Bruno.

- ↑ Letter, Fujita to Strong, Aug. 9, 1942.

- ↑ Letter, Ihara to "Barbara," May 13, 1942.

- ↑ Violet Kunimoto Kimoto interview, 56.

- ↑ Letter, Fujita to Strong, Aug. 9, 1942.

- ↑ Burton, et al., Confinement and Ethnicity , 357; Barbara Wyatt, ed., Japanese Americans in World War II: National Historic Landmarks Theme Study (Washington, D.C.: National Historic Landmarks Program, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2012), 113.

- ↑ Burton, et al., Confinement and Ethnicity , 357; Wyatt, ed., Japanese Americans in World War II ," 113.

- ↑ Kenji G. Taguma, "Etched into History: Merced Assembly Center Memorial Unveiled," Nichi Bei Weekly , Mar. 4, 2010, https://www.nichibei.org/2010/03/photo-available-etched-into-history-merced-assembly-center-memorial-unveiled/ ; The Merced Assembly Center: Injustice Immortalized, streaming at PBS website, https://www.pbs.org/video/byyou-exploration-merced-assembly-center-memorial/ .

Last updated Dec. 30, 2020, 8:42 p.m..

Media

Media