National Japanese American Student Relocation Council

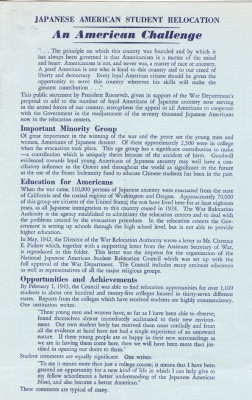

The National Japanese American Student Relocation Council (NJASRC) worked during World War II to help resettle inmates from the government's concentration camps to colleges in the Midwest and the East Coast. Under the sponsorship of the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), the Council worked with students, their families, and the larger Japanese American community as well as a wide range of public and private organizations in ultimately helping more than 4,000 students resettle to pursue their higher education at more than 600 institutions.

The Creation of the NJASRC

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor shocked Japanese Americans, and college students, like others in the community, worried what might come next. Anxious students at the University of Washington, for example, struggled to come to grips with a suddenly uncertain future, worrying about racial violence and even raising the possibility of concentration camps, especially for their non-citizen parents. As an associate in the Department of Sociology somewhat despairingly asked, "Well here we are at last. But where do we go from here, in particular where do we Nisei go from here?" [1]

Answers to such fundamental questions for Japanese American college students came only very slowly in the chaotic times that followed. As the government decisively moved toward a policy of mass removal and confinement, these students chose different options. Some complied with military orders, hoping in various cases to prove their loyalty or to care for their families. Others, feeling disillusioned and hopeless, saw no way to avoid incarceration and the interruption of their educations. But at least some actively began to look for ways to continue their higher education away from the West Coast and life behind barbed wire. As they did so, sympathetic college administrators and others attempted to help, creating uncoordinated efforts with mixed results.

The creation of the NJASRC on May 29, 1942, almost three months after Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 , finally provided a government-approved route to student resettlement . Led by the AFSC at the request of War Relocation Authority (WRA) director Milton S. Eisenhower , the Council faced a daunting task. It would have to work with a dizzying array of groups—civilian and military branches of the government, philanthropic foundations, college administrators, and church mission boards in addition to the students and their parents—to raise money, find openings in welcoming locales, and fashion a process for and then facilitate resettlement, all in a hostile wartime context.

To accomplish all of this, the Council from the start emphasized the importance of resettled students serving as "ambassadors of good will," a role that many students willingly adopted. As an editorial in the Santa Anita Pacemaker emphasized, Japanese American students would face intense scrutiny and must be up to their task: "Upon their scholarship, their conduct, their thoughts, their sense of humor, their adaptability, will rest the verdict of the rest of the country as to whether Japanese Americans are true Americans. So, upon the students will be the onus of proving to people to whom they are strangers that the first word in 'Japanese American' is merely an adjective describing the color of our skin—not the color of our beliefs." [2]

The NJASRC at Work

The NJASRC's success clearly depended upon its ability to work with a wide range of groups, and Quaker leaders such as Clarence Pickett always emphasized the broadly cooperative nature of this endeavor. From the start, the Council knew that its success would rest on its ability to compromise with the government in crafting a shared vision of student resettlement. Such work began with the military's Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) in its temporary assembly centers, where the NJASRC faced intense scrutiny. Even the transfer of inmates to the somewhat more amenable WRA and its facilities hardly overcame all obstacles. Inside the camps, some individual administrators and high school teachers discouraged inmates from pursuing higher education, despite WRA support for student resettlement. Still, the WRA undoubtedly contributed to the Council's success, despite occasional problems along the way. Military regulations (on matters such as release from the concentration camps) and swiftly changing policies about which colleges were open to Japanese Americans and which were not presented shifting and difficult problems. In addition to working with WRA and military personnel to resettle students, the NJASRC also received help from higher-ranking government officials, including Roosevelt, who promised opportunities for the Japanese American students, and even Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy and Assistant to the Secretary of the Navy Adlai Stevenson, who helped to unlock bottlenecks in the process of clearing students for release. While the relationship between the NJASRC and government agencies was not always smooth (and occasionally proved quite confrontational), the Council managed to forge a workable arrangement that, after a frustratingly slow start, ultimately allowed almost all students who wanted to pursue a higher education to do so.

In addition to working with this wide range of government agencies and personnel, Council members also had to work outside the concentration camps to open opportunities for resettlement. From the start, the AFSC understood that it could not finance the entire operation (and that the government would not, either), and it turned to a number of groups for help. Foundations such as the Carnegie Corporation and the Columbia Foundation played a pivotal role in providing the initial and continued funding needed to cover administrative costs. Church mission boards also provided important financial support, often in the form of scholarships that enabled inmates to afford higher education. Such groups provided additional and much-needed help in lobbying denominational schools to accept Japanese American students and to build positive welcomes for them not only on campus but in the wider local community as well. A wide range of others, including local and national Y's and innumerable local community groups as well as interested college administrators and faculty in both the West and East helped to open doors and support the movement of students from concentration camp to campus.

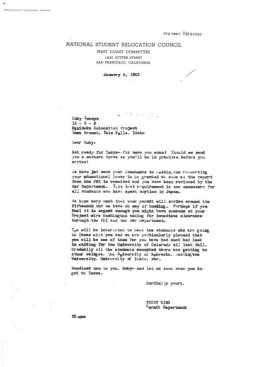

As it worked to open the way for student resettlement, the NJASRC had to negotiate internal tensions as well, often pitting East Coast personnel such as John W. Nason and a series of Council directors, who tended to be pragmatic and emphasize the importance of caution in pursuing slow and steady progress, versus West Coast personnel such as Thomas Bodine , Trudy King, and others, who adopted a more crusading attitude and encouraged the inmates to skirt WRA rules whenever advantageous. The easterners, with their professional focus on organization and results, managed to maintain fairly positive relations with government and military agencies, even when critical westerners bluntly criticized their handling of removal and confinement. The westerners' approach provided important balance inside the concentration camps, however, where their willingness to criticize authority created an important distance in inmates' perceptions of the WRA and the NJASRC. The westerners also emphasized creating personal relationships with each student they attempted to help, providing an important counterweight to the emphasis placed on efficiency by some in the East. This emphasis on personal relations was fostered through letters that treated each student as a person (and not a case) and the almost indefatigable Bodine, who visited the camps to build close relationships in his role as field director of the NJASRC. While internal bickering might have occasionally slowed Council efforts, in the long run these internal dynamics allowed the Council to cultivate strong relationships with Japanese Americans and the WRA, necessities if student resettlement were to succeed.

And the Japanese Americans themselves, of course, ultimately contributed the most to the success of the NJASRC's program. Inside the camps, support came from a variety of sources. Camp-wide scholarship drives raised essential money that allowed students to move. The Issei valued education, and they worked in various ways to reinforce Council efforts. While some worried parents and others did question the program, most of the inmates proved very supportive of the students, who in turn often chose to become "ambassadors of good will" who might open the way for broader and faster resettlement programs aimed at securing freedom for more Japanese Americans. At the least, as students pioneered "permanent" resettlement, they demonstrated that other members of the community might look forward to their own release. Some also made return visits to the camps to emphasize the possibilities of resettlement. Once outside the camps, some of these students ambitiously promoted multiculturalism. As Nao Takasugi explained in arguing that student resettlement might reform the wider society, personal contact between Japanese Americans and whites could lead "to prejudice and discrimination [giving] way to understanding and friendship." [3] Such high ideals, of course, were not always met, as one student recalled that "at Wheaton I was always one of the foreign students. No one could get it through their heads that I wasn't foreign." [4] Still, the positive reception of Japanese American students on many campuses played a role in the movement toward multiculturalism that thrives on college campuses today.

As they resettled, college students often felt pressure from the WRA and even some in the NJASRC to disperse and assimilate. While some did, many resisted this challenge to Japanese American identity, working instead to build their own meanings for their wartime experiences. While resettlement undoubtedly opened up new opportunities for women and the students generally, many chose to be ambassadors of multiculturalism (instead of just good will), continuing to acculturate, to be sure, but also maintaining ties with the Japanese American community and their cultural heritage. In this way, the college students reaffirmed that "the war at once underwrote assimilation and ethnic assertiveness, a paradox consistent with the wartime blend of national unity and cultural pluralism." [5]

The NJASRC wrote to students on June 7, 1946, to announce its closing, hoping that this decision was a sign that Japanese Americans were successfully adapting to their new communities. Understanding, too, that the students would continue to face challenges for some time after it closed, the Council made suggestions for handling the issues—especially in terms of financial support for those still enrolled in colleges and universities—that it anticipated might arise. Relating how much staffers had enjoyed working with them, the Council's letter reemphasized one last time the personal relationships that members hoped to cultivate with students.

The Legacy of the NJASRC

The legacy of the NJASRC and its work has proved lasting, as exemplified by the creation of the Nisei Student Relocation Commemorative Fund in 1980. This agency, founded by Japanese Americans resettled during the war, awarded scholarships to Southeast Asian refugee students, ignoring the assimilative aspects of wartime aid to emphasize instead the opportunities offered by higher education both then and now. Emphasizing the philosophy of ongaeshi (recognizing and returning thanks for acts of kindness), the Fund kept in close touch with the students it aided, and the letters from the refugee students often echoed messages and themes first penned by Japanese American students some fifty years earlier.

Having gone to work in tense times on controversial work, the NJASRC, despite occasional missteps to be sure, helped Japanese American students take optimistic actions that asserted their future in the U.S. Acting together, concerned white liberals and Japanese Americans managed at least to ameliorate the damages inflicted by the government's policy of mass removal and confinement. In doing so, the story of student resettlement highlights "not only the prevailing racism [of the WWII era], but also the efforts of a few to mitigate it." [6]

For More Information

AFSC Oral History Interviews. Philadelphia: AFSC, 1991.

American Friends Service Committee Archives, Philadelphia.

Austin, Allan W. From Concentration Camp to Campus: Japanese American Students and World War II . Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Thomas R. Bodine Papers. Hoover Institution. Stanford University.

"Interrupted Lives." University of Washington online document. http://www.lib.washington.edu/exhibits/harmony/Uw-new .

Ito, Leslie A. "Japanese American Women and the Student Relocation Movement, 1942-1945." Frontiers 21 (2000): 1-24.

———. "Loyalty and Learning: Nisei Women and the Student Relocation." Honors Thesis, Mount Holyoke College, 1996.

James, Thomas. Exile Within: The Schooling of Japanese Americans, 1942-1945 . Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 1987.

———. "Life Begins with Freedom: The College Nisei, 1942-1945." History of Education Quarterly 25 (1985): 155-174.

Jeffries, John W. Wartime America: The World War II Homefront . Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1996.

National Japanese American Student Relocation Council Papers. Hoover Institution. Stanford University.

O’Brien, Robert W. The College Nisei . Palo Alto: Pacific Books, 1949.

Okihiro, Gary Y. Storied Lives: Japanese American Students and World War II . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999.

Smith, Mildred Joan. "Backgrounds, Problems, and Significant Reactions of Relocated Japanese-American Students." Ed.D., Syracuse, 1949.

Footnotes

- ↑ Allan W. Austin, From Concentration Camp to Campus: Japanese American Students and World War II (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004), 7.

- ↑ Austin, From Concentration Camp to Campus , 3.

- ↑ Austin, From Concentration Camp to Campus , 166.

- ↑ Leslie A. Ito, "Japanese American Women and the Student Relocation Movement, 1942-1945," Frontiers 21 (2000): 58-59.

- ↑ John W. Jeffries, Wartime America: The World War II Homefront (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1996), 136.

- ↑ Austin, From Concentration Camp to Campus , 172.

Last updated Oct. 8, 2020, 4:03 p.m..

Media

Media