American Friends Service Committee

Created in 1917 to aid conscientious objectors, the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) had embarked on a more ambitious agenda by the mid-1920s that included attempts to ameliorate race relations in the U.S. After working with Japanese college students in the 1920s, the AFSC became actively involved with Japanese Americans during World War II. While its efforts to help extended across a wide range of activities, the AFSC focused on Japanese American resettlement , taking lead of the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council (NJASRC) and establishing hostels in several U.S. cities to help Japanese American resettlers adjust to life in their new communities.

Prewar Activism

Although originally established by Quakers to provide alternatives to military service for conscientious objectors during World War I, the AFSC soon decided to work on a wider range of issues. As a result, by the mid-1920s, AFSC leaders had committed their organization to interpreting the Friendly way of life in Europe, increasing its home service program, promoting pacifism, and applying Quaker principles and ideals to improving race relations. To help achieve better interracial relations, the AFSC created the Interracial Section in 1924, which addressed racial issues in a global context that transcended simple binaries of black and white.

Emphasizing the importance of intercultural connections as the best means to pursue its ambitious program, the Interracial Section focused primarily on work with African Americans and Japanese. The latter effort focused on supporting the studies of three Japanese students at U.S. colleges for an academic year. Hoping that the resulting contacts between American and Japanese students would lead to improved understanding and friendship, Interracial Section members financed three Japanese scholars—Yasushi Hasegawa, Kiyo Harano, and Tadosaku Ito—with somewhat mixed results. Believing that Hasegawa had accomplished important work, AFSC leaders worried that the other students had contributed less, in part because of their struggles with the English language. Facing financial problems and an ambitious range of projects, the AFSC ended the Japanese student program in the late 1920s, not long before deciding to close the Interracial Section as well. The latter decision—grounded in concerns about financing, overlapping responsibilities for interracial work among various sections of the AFSC, and a diminished momentum for Interracial Section projects—did not, however, end AFSC interest in interracial activism, and the organization spent the late 1920s and the Great Depression working with first the American Interracial Peace Committee and later the Institute of Race Relations.

Wartime Activism

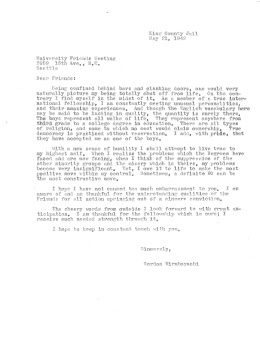

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the ensuing government decision for mass removal and confinement resulted in a series of crises for Japanese Americans living on the West Coast, and the AFSC, with almost two decades of experience with interracial activism and an historic interest in U.S.-Japanese relations, quickly began searching for ways to help them. Hoping to extend, in Quaker Thomas Bodine 's words, "spiritual handshakes" to Japanese Americans facing wartime troubles, AFSC staffers soon found the magnitude of problems overwhelming their small West Coast office. [1] As they tried to assess the quickly changing situation on the ground, Quakers visited Japanese Americans, first in their homes and later in the camps, to provide moral support and to find out what help was needed, spoke publically about the situation, and collected food for hungry families. As it found its footing, the AFSC eventually focused its efforts on two major projects, both related to programs designed to resettle inmates in the midwestern and eastern U.S.

The AFSC first attempted to help resettlement efforts by assuming, at War Relocation Authority (WRA) director Milton S. Eisenhower 's request, leadership of the NJASRC. Created on May 29, 1942, the Council was quite successful, helping to resettle more than 4,000 college students at more than 600 institutions of higher learning. The success came as the result of hard and dedicated work in very challenging circumstances. Short on cash and working in a hostile wartime context, the NJASRC had to forge cooperative relationships with a wide range of public and private agencies and individuals, including civilian and military branches of the government, philanthropic foundations, college administrators, and church mission boards as well as the Japanese American students, their parents, and the wider incarcerated community.

The NJASRC also faced internal divisions. It was staffed on the East Coast with a number of pragmatic leaders like John W. Nason , who focused on slow but steady progress and emphasized the importance of maintaining good relations with the WRA and other government and military agencies. On the West Coast, a more radical outlook developed, and workers here at times bluntly criticized the government and encouraged students to do what was best for themselves, even if this meant skirting government regulations. This divide created tensions within the NJASRC from time to time, but in the long run proved beneficial, allowing the Council to maintain a cooperative relationship with the WRA while also appealing to inmates as an organization that understood and even protested what had been done to them.

The success of the NJASRC also depended upon, most importantly, the efforts of Japanese Americans, especially the students, many of whom accepted acting as "ambassadors of good will" as part of their responsibilities. In this way, the Council and the students hoped to demonstrate Japanese American loyalty and assimilation, in the process blazing a path for broader efforts at resettlement. In doing so, the students acted as pioneers opening the way for others to follow. Some went even further, seizing an opportunity—encouraged by more outspoken Council members like Bodine—to reform the broader society as well, in the process promoting a nascent multiculturalism that would continue to grow and eventually flourish after the war.

Having accumulated experience with Japanese American resettlement through the NJASRC and having worked with European refugees during the early years of the global conflict, the AFSC also logically turned to opening hostels as another way to support further the movement of inmates back into free society. AFSC leaders opened hostels in 1943 in Chicago, Cincinnati , and Des Moines ; in 1944, they opened another hostel in Philadelphia while supporting hostels run by other organizations in Detroit, Minneapolis, and New York City. The AFSC later established hostels in Pasadena and Los Angeles to help Japanese Americans returning to the West Coast.

As AFSC staffers began to open hostels, they faced many problems. Red tape was an ever-present problem, and Quakers struggled to locate jobs for Japanese Americans and then obtain releases in a timely manner. An increasing hesitancy on the part of some to leave the camps made the job more difficult, as did the Eastern Defense Command's reluctance to allow Japanese Americans to migrate into territory under its jurisdiction. Finding the funding to carry out its efforts, always a concern for the cash-strapped AFSC, remained a challenge throughout the war, too. Internally, staffers argued about the merits of dispersal—a key WRA goal for resettlement—but at least agreed on the importance of intercultural contacts as the key to building positive future relations between whites and Japanese Americans. To prepare local communities for the arrival of Japanese Americans, the AFSC talked with local agencies and leaders. After Japanese Americans arrived, the job of "interpretation" continued, with the Service Committee encouraging newcomers to visit and speak with local groups while also using the press to explain the situation faced by Japanese Americans. To help the resettlers further, the AFSC encouraged local Friends and others in the local community to develop relationships with them, and hostels held meetings for worship, open houses, teas, holiday parties, and sewing groups to foster such connections.

Run as cooperative enterprises, the hostels focused on securing employment and housing for the new Japanese American arrivals. Jobs were the easier part of this work, although some did struggle to find placements. Housing remained the more daunting problem, with already tight housing markets being at least occasionally reinforced by prejudiced landlords. Once in their new communities, many Japanese Americans enjoyed success, but many found that racism continued to circumscribe their lives as well, running into social and economic barriers based on prejudice. Despite their success (amid such shortcomings), as demand lessened in the camps and local needs outside the camps were met, the AFSC's hostels were relatively short-lived. The Cincinnati hostel, the last to close, was shuttered on January 1, 1946.

Postwar AFSC

While the AFSC moved on to new issues in 1946, its wartime experiences with European refugees and Japanese Americans shaped its future activism. Convinced by their WWII interracial activism of the need for a broader approach to race relations, the AFSC approached the early Cold War era with an emphasis on race relations as community relations, a shift in strategy that would underlie AFSC programming as the Civil Rights Movement began. The AFSC and the British Friends Service Council received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1947 on behalf of Quakers worldwide.

For More Information

American Friends Service Committee Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Austin, Allan W. Quaker Brotherhood: Interracial Activism and the American Friends Service Committee, 1917-1950 . Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012.

———. "'Let's do away with walls!': The American Friends Service Committee's Interracial Section and the 1920s United States." Quaker History 98:1 (2009): 1-34.

———. From Concentration Camp to Campus: Japanese American Students and World War II. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Okihiro, Gary Y. Storied Lives: Japanese American Students and World War II. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999.

Footnotes

- ↑ Allan W. Austin, Quaker Brotherhood: Interracial Activism and the American Friends Service Committee, 1917-1950 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012), 13.

Last updated March 3, 2015, 7:53 p.m..

Media

Media