Munson Report

Intelligence report on Japanese Americans on the West Coast filed by businessman Curtis B. Munson in the weeks prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor at the request of presidential envoy John Franklin Carter. Based on first hand research and consultation with navy and Federal Bureau of Investigation agents, the report largely concluded that Japanese Americans presented no security risk. A misleading summary of the report sent by Carter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt may have contributed to the report and its conclusions being largely ignored by the administration.

Background

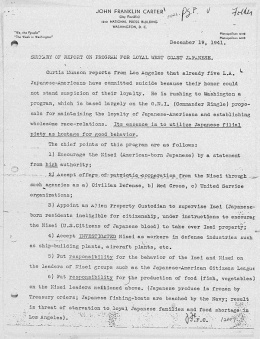

In early 1941, the President was unsatisfied with the state of intelligence on Japanese Americans as the state of relations between Japan and the U.S. deteriorated. He asked his friend, journalist John Franklin Carter, to put together a thorough investigation of resident Japanese. He hired several investigators, one of whom was Curtis B. Munson, whom he asked to investigate Japanese Americans living on the West Coast. Though Munson, a wealthy businessman from the Midwest, had no formal training in intelligence work, he had conducted investigative work for the president before, having reported on Martinique to the President's satisfaction.

Investigation and Reporting

Munson headed to the West Coast in the fall of 1941, spending about a week each in the 11th, 12th, and 13th Naval Districts, encompassing the entire West Coast. He met with investigators from the FBI and Office of Naval Intelligence and interviewed Japanese Americans and those who knew them.

He filed his first preliminary report to Carter in October. The report would reflect the general tenor of his conclusions in all of the reports he would subsequently file. "We do not want to throw a lot of American citizens into a concentration camp of course, and especially as the almost unanimous verdict is that in case of war they will be quiet, very quiet," he wrote. "There will probably be some sabotage by paid Japanese agents and the odd fanatical Jap, but the bulk of these people will be quiet because in addition to being quite contented with the American Way of life, they know they are 'in a spot.'" [1]

Carter passed these on to FDR, adding, "The essence of what [Munson] has to report is that, to date, he has found no evidence which would indicate that there is danger of widespread anti-American activities among this population group. He feels that the Japanese are more in danger from the whites than the other way around." [2]

Munson's final report went to the president on November 7. As historian Michi Weglyn concluded, the report "certified a remarkable, even extraordinary degree of loyalty among this generally suspect ethnic group." [3] He divided the Japanese Americans into four groups: Issei , Nisei , Kibei , and Sansei . Dismissing the Sansei because they were mostly children, he focused on the other three groups.

Of the Issei, he noted that they are "considerably weakened in their loyalty to Japan by the fact that they have chosen to make this their home and have brought up their children here." "They expect to die here," he wrote. [4] He described the Nisei as "universally estimated from 90 to 98 percent loyal to the United States if the Japanese-educated element of the Kibei is excluded. The Nisei are pathetically eager to show this loyalty. They are not Japanese in culture. They are foreigners to Japan." While conceding that the Kibei "are considered the most dangerous element," he also notes "that many of those who visited Japan subsequent to their early American education come back with added loyalty to the United States. In fact it is a saying that all a Nisei needs is a trip to Japan to make a loyal American out of him." [5]

As for Japanese Americans being potential saboteurs, Munson makes the key point that they "are hampered as saboteurs because of their easily recognized physical appearance. It will be hard for them to get near anything to blow up if it is guarded ." [6]

He concludes, "As interview after interview piled up, those bringing in results began to call it the same old tune. The story was all the same. There is no Japanese 'problem' on the Coast. There will be no armed uprising of Japanese." [7]

Unfortunately for Japanese Americans, Carter sent the report to FDR with his own one-page summary of key points. This summary—which may be all that the president read—managed to largely obscure Munson's conclusions and may have inadvertently had the effect of alarming the President further.

Among the points highlighted by Carter: while stating that "There is no Japanese 'problem' on the coast," he followed that up with "There will be the odd case of fanatical sabotage by some Japanese 'crackpot'" "There are still Japanese in the United States who will tie dynamite around their waist and make a human bomb, but today they are few," he wrote. The last highlighted point was that "Your reporter... is horrified to note that dams, bridges, harbors, power stations, etc. are wholly unguarded everywhere." [8] Of the "dynamite" statement, Greg Robinson notes that Carter left out a prior sentence by Munson that seems to indicate that that the "dynamite" statement referred to paid Japanese agents and not Japanese Americans. [9]

The President read Carter's statement immediately and sent the report on to Secretary of War Henry Stimson with a note highlighting the "guarding of key points." [10]

Aftermath

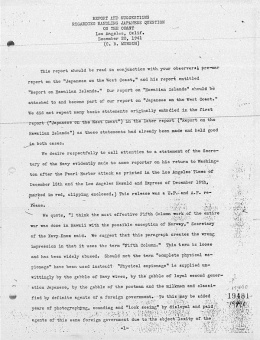

Following Munson's West Coast investigations, he went on to Hawai'i to continue his work. His report on Hawai'i—which reached largely the same conclusions as his West Coast report—went to the President on December 8, a day after the attack on Pearl Harbor. He sent additional reports to Carter between December and February. A report received by the President on December 22 noted that the attack on Pearl Harbor had resulted in no fifth column activity, writing that the "attack is the proof of the pudding" of his conclusions. [11]

Subsequently, Munson, along with Carter and Kenneth Ringle of the Office of Naval Intelligence, recommended to the president what Michi Weglyn calls a "power-to-the-Nisei" policy, essentially giving them responsibility of policing the community: "The aim of this will be to squeeze control from the hands of the Japanese Nationals into the hands of the loyal Nisei who are American citizens.... It is the aim that the Nisei should police themselves, and as a result police their parents." [12] The trio also called for a public statement in support of the Nisei. Though the President expressed support for the plan, nothing ever came of it. No such statement was issued and Western Defense Command head John L. DeWitt refused to meet with them. The Munson Report was largely forgotten until it was highlighted in Michi Weglyn's landmark Years of Infamy book in 1976.

For More Information

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians . Foreword by Tetsuden Kashima. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997.

Munson, Curtis B. "Japanese on the West Coast." In American Concentration Camps: Volume 1, July, 1940—December 31, 1941 , edited with an introduction by Roger Daniels. New York: Garland Publishing, 1989.[The full Munson Report and John Franklin Carter's introductory memo.]

Robinson, Greg. By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans . Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Weglyn, Michi. Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America's Concentration Camps . New York: William Morrow & Co., 1976. Updated ed. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996.

Footnotes

- ↑ Greg Robinson, By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), 66.

- ↑ Robinson, By Order of the President , 66.

- ↑ Michi Weglyn, Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America's Concentration Camps (New York: William Morrow & Co., 1976. Updated ed. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996), 34.

- ↑ Weglyn, Years of Infamy , 44.

- ↑ Ibid., 41–42.

- ↑ Ibid., 45–46.

- ↑ Ibid., 45.

- ↑ Klancy Clark de Nevers, The Colonel and the Pacifist: Karl Bendetsen, Perry Saito and the Incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2004), 96.

- ↑ Robinson, By Order of the President , 68.

- ↑ Ibid., 68.

- ↑ Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997), 53.

- ↑ Weglyn, Years of Infamy , 51.

Last updated April 4, 2024, 9:57 p.m..

Media

Media