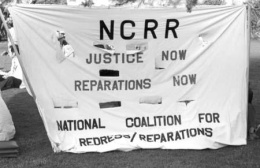

National Coalition for Redress/Reparations

The National Coalition for Redress/Reparations (NCRR) was one of three national Japanese American organizations that pushed for redress and reparations for the wartime removal and incarceration of West Coast Japanese Americans. Formed in 1980, NCRR, like the National Council for Japanese American Redress (NCJAR), came about in part to challenge the leadership, perspective, and strategy of the more mainstream Japanese American Citizens League . At the hearings of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) in 1981, NCRR arranged for the testimony of a wide range of Japanese American community members as opposed to the Nisei elites favored by JACL and encouraged a more confrontational approach that drew parallels with other racial and ethnic groups. The group also sponsored a direct reparations bill in Congress in 1982 introduced by California Congressman Mervyn Dymally. After the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 , NCRR worked to seek redress for as many people as possible under the provisions of the act and also supported the efforts of Japanese Latin Americans who were explicitly excluded from the legislation. In 2000, the organization became Nikkei for Civil Rights & Redress, maintaining the same NCRR acronym.

Origins

The roots of NCRR can be traced to Los Angeles area activists, many of whom were protesting the evictions of Japanese Americans during the "redevelopment" of the historic Little Tokyo area. Members of the Little Tokyo People's Right Organization—who were mostly Sansei born after the war who had been inspired by 1960s social movements—saw a connection between the evictions of mostly poor Issei and Nisei from Little Tokyo and the mass wartime removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast, tracing both to forms of racism and economic interests. In the spring of 1979, when the National Committee for Redress (NCR) of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) announced a strategy of asking Congress to appoint a commission to study the wartime removal and incarceration rather than for direct monetary reparations the wartime injustice, these activists formed the Los Angeles Community Coalition for Redress/Reparations (LACCRR). Explicitly endorsing reparations, the group began to hold educational forums in the community. [1]

NCRR officially formed on July 12, 1980, and included Nisei and Sansei from LACCRR as well as members of like-minded organizations from throughout the country including the Japanese Community Progressive Alliance (San Francisco), Tule Lake Committee, Nihonmachi Outreach Committee (San Jose), and Asian/Pacific Student Union, along with some members of the JACL. The new organization formed around five principles of unity, which including a specific call for individual monetary reparations, as well as support for other groups "suffering from unjust actions taken by the United States government." NCRR's founding conference took place on the campus of California State University, Los Angeles on November 15-16, 1980, and featured a keynote address by wartime dissident Gordon Hirabayashi . [2]

CWRIC Hearings and Lobbying

Though it had formed in part out of opposition to the proposed study commission, NCRR members decided that once the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) had been formed and had announced it would hold hearings in the summer of 1981, that they would work to ensure as a broad a spectrum participated in the hearings as possible. To that end, NCRR pushed for Japanese translators to enable Issei and Kibei to comfortably testify and night hearings so that working people could attend. In contrast to the JACL, NCRR encouraged those who testified to express their anger and frustrations and to note the broader injustice of the wartime exclusion and incarceration and the connections to other injustices other groups had suffered. As NCRR member and chronicler Glen Kitayama wrote, "Because of the success of the hearings, the NCRR gained the respect of the Japanese American community and along with it, political clout." [3]

After the hearings, NCRR worked with Congressman Mervyn Dymally, a freshman Democrat representing the Gardena, California area, on two redress bills, one calling for individual compensation of $25,000 person and another calling for a $3 billion trust fund. Knowing that the bills would not pass, the group pushing for them anyway to demonstrate the seriousness with which Japanese Americans viewed the issue and as a means to gauge potential support for future legislation. [4]

Though NCRR's position on the amount of individual compensation did not differ that much from the JACL's, the group viewed the meaning and significance of the wartime incarceration differently. As Redress Movement historian Alice Yang Murray saw it, NCRR "activists often linked the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans with the confinement of Native Americans on reservations, the enslavement of African Americans, and the economic exploitation of Asian immigrant laborers. That is, they emphasized the importance of viewing internment within the context of a long history of racial and economic oppression against people of color." Anthropologist Lane Hirabayashi, who was an early member of NCRR, also observed that the group was the only one that specifically sought a community fund to "compensate for damages to, if not the overall destruction of, pre-World War II Japanese American communities" based on a view that wartime policies brought about a collective loss for these communities. While pushing for reparations, NCRR also supported the struggles of other groups, for instance protesting the government's 1986 order that Navajos leave Big Mountain in Arizona, explicitly likening it to Japanese American exclusion. [5]

While various reparations bills were introduced in Congress after the CWRIC issued its recommendations in 1983, NCRR launched letter-writing campaigns in coordination with the JACL and took two lobbying trips to support the legislation. The second trip, in the summer of 1987 came to involve 120 people and ended up "as the largest Asian American contingent ever to hit the halls of Congress." [6]

NCRR also took a leading role in the successful campaign to oppose the confirmation of Dan Lungren—the lone member of the CWRIC to oppose monetary reparations—as California state treasurer in 1988. [7]

After Redress

After the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, the NCRR worked closely with the Office of Redress Administration to qualify as many Japanese Americans as possible for monetary reparations under its terms. NCRR worked many with groups that initially denied redress and was able to launch successful campaigns to secure redress for some, such as railroad and mine workers fired after the after the attack on Pearl Harbor and the children of Japanese Americans who returned to Japan during the war. One of the largest groups denied redress were the Japanese Latin Americans (JLA) who had been forcibly brought to the U.S. to serve as hostages to be exchanged with Americans held by Japan. NCRR members were among those who founded the Campaign for Justice, an organization that continues to fight for redress for the JLA group. [8]

As redress activities wound down in the 1990s, NCRR changed its name to "Nikkei for Civil Rights & Redress," to reflect a broader mission while maintaining the same acronym. One focus of its efforts was on education. Having organized Los Angeles area Days of Remembrance since 1981, NCRR continued to put on the annual events with a variety of partners. NCRR also received a series of California Civil Liberties Public Education Program grants to produce a film titled Stand Up for Justice , in collaboration with Visual Communications . Directed by John Esaki, the film tells the story of Ralph Lazo , a Mexican-Irish American who accompanied his Japanese American friends to Manzanar in a show of solidarity. [9]

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, NCRR reached out to Arab and Muslim American communities. A candlelight vigil soon after the attacks led to a series of "Breaking the Fast" programs in the early 2000s, joint celebrations of the end of Ramadan put on in collaboration with the Muslim Public Affairs Council. NCRR, along with the JACL and the Council on American Islamic Relations and the Shura Council, launched the Bridging Communities Program in 2008, a high school program bringing together Japanese American and American Muslim youth. NCRR also opposed the War in Iraq in 2003 and supported dissident American soldiers Agustin Aguayo and Ehren Watada and army chaplain James Yee. [10]

Redress Movement chroniclers acknowledge NCRR's important role building grassroots support for the movement. Mitchell Maki, Harry Kitano , and S. Megan Berthold call NCRR "the expressive voice of the movement" that "helped broaden the support for redress, both inside and outside the Japanese American community," while Leslie Hatamiya cites as their greatest contribution that "they brought the movement home to Japanese Americans and got the community excited about what was happening." Congressman Robert Matsui called NCRR's "grassroots campaign for redress ... an impressive testament to citizen activism to correct injustice." [11]

Authored by

Brian Niiya

, Densho

For More Information

Hirabayashi, Lane Ryo. "Community Destroyed? Assessing the Impact of the Loss of Community on Japanese Americans during World War II." In Re/Collecting Early Asian America: Essays in Cultural History . Edited by Josephine Lee, Imogen L. Lim, and Yuko Matsukawa. Philadelpha: Temple University Press, 2002. 94–107.

Kitayama, Glen Ikuo. "Japanese Americans and the Movement for Redress: A Case Study of Grassroots Activism in the Los Angeles Chapter of the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations." M.A. thesis, UCLA, 1993.

Maki, Mitchell T., Harry H.L. Kitano, and S. Megan Berthold. Achieving the Impossible Dream: How Japanese Americans Obtained Redress . Forewords Robert T. Matsui and Roger Daniels. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999.

Murray, Alice Yang. Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress . Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008.

NCRR website and online archive, https://www.ncrr.com/ .

Footnotes

- ↑ Glen Ikuo Kitayama, "Japanese Americans and the Movement for Redress: A Case Study of Grassroots Activism in the Los Angeles Chapter of the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations," M.A. Thesis, UCLA, 1993, 47–50.

- ↑ Kitayama, "Japanese Americans and the Movement for Redress," 50–56. LACCRR effectively ceased to exist after this conference, its members forming the core of NCRR.

- ↑ Alice Yang Murray, Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008), 314–19; Kitayama, "Japanese Americans and the Movement for Redress," 66.

- ↑ Mitchell T. Maki, Harry H.L. Kitano, and S. Megan Berthold, Achieving the Impossible Dream: How Japanese Americans Obtained Redress (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999), 110; Kitayama, "Japanese Americans and the Movement for Redress," 67–68.

- ↑ Murray, Historical Memories , 4, 440; Lane Ryo Hirabayashi, "Community Destroyed? Assessing the Impact of the Loss of Community on Japanese Americans during World War II," in Re/Collecting Early Asian America: Essays in Cultural History , edited by Josephine Lee, Imogen L. Lim, and Yuko Matsukawa (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002), 95–96; Kitayama, "Japanese Americans and the Movement for Redress," 78.

- ↑ Kitayama, "Japanese Americans and the Movement for Redress," 81–84; Maki, et al., Achieving the Impossible Dream , 142, 172–73; Leslie T. Hatamiya, Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and the Passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993), 164. Quote from Hatamiya.

- ↑ Kitayama, "Japanese Americans and the Movement for Redress," 85–87.

- ↑ Maki, et al., Achieving the Impossible Dream , 217; NCRR online archives, accessed on Sept. 3, 2014 at NCRR website: http://www.ncrr-la.org/NCRR_archives/welcome.htm .

- ↑ NCRR online archives, accessed on Sept. 3, 2014 at NCRR website: http://www.ncrr-la.org/NCRR_archives/welcome.htm ; Alexandra L. Wood, "After Apology: Public Education as Redress for Japanese American and Japanese Canadian Confinement," Ph.D. dissertation, New York University, 2013, 222–23. According to Kitayama, the name change took place at the 10th anniversary conference in 1990. However, NCRR newsletters continued to use the old name until 2000.

- ↑ Masumi Izumi, "Seeking the Truth, Spiritual and Political: Japanese American Community Building through Engaged Ethnic Buddhism," Peace & Change 35.1 (Jan. 2010), 55–57; NCRR online archives, accessed on Sept. 3, 2014 at NCRR website: http://www.ncrr-la.org/NCRR_archives/welcome.htm .

- ↑ Maki, et al., Achieving the Impossible Dream , 187; Hatamiya, Righting a Wrong , 164; Matsui quote cited in Murray, Historical Memories , 367.

Last updated March 17, 2024, 5:16 a.m..

Media

Media