Japanese Latin Americans

During World War II, the United States interned thousands of Japanese, Germans, and Italians deported from Latin America to internment camps operated by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). Without proper documentation such as visas and passports the deportees were considered " enemy aliens " subject to internment, despite the fact that some deportees were citizens of Latin American countries. According to historians' estimates, the United States interned nearly 1,800 Japanese from Peru, 250 Japanese from Panama, and substantial numbers from Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Venezuela. Though it briefly considered exchanging Japanese Latin Americans for American civilians held captive abroad, the United States government primarily justified the deportation-internment program on the grounds of hemispheric security.

Most Japanese Latin Americans ended up at INS camps in Santa Fe , New Mexico, and Kenedy , Seagoville , and Crystal City , Texas, before the United States repatriated them to Japan. Under the jurisdiction of the Justice Department, the INS camps were administered separately from the War Relocation Authority centers that incarcerated Japanese Americans. After the war, a few internees returned to Latin America while several hundred remained in the United States as undocumented "immigrants." Decades later, the United States government maintained that it was not responsible for the internment of Japanese Latin Americans, and they were excluded from the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 .

Before the War

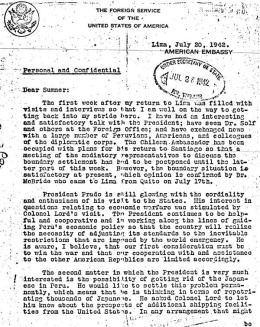

As hostilities developed in Asia and Europe during the 1930s, the United States became increasingly concerned with Axis subversion in the Western Hemisphere. In December 1938, delegates to the Eighth International Conference of American States in Lima, including United States Secretary of State Cordell Hull, affirmed their "continental solidarity" and agreed to "defend against all foreign intervention or activity." [1] Despite these cooperative efforts, the United States remained skeptical of Latin American leaders' ability and willingness to counter Axis activity. In July 1940, President Franklin Roosevelt authorized the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) to station agents, known as legal attachés, at U.S. embassies throughout Latin America. These agents gathered intelligence and generated what they called a "Proclaimed List" of individuals suspected of harboring Axis sympathies.

Latin American countries offered varying degrees of support. In October 1941, Panama and the United States agreed that in the event of war, the former would arrest Japanese outside of the Canal Zone and that the latter would pay the expenses for their internment on Taboga Island. [2] Indeed, most Central American countries were eager to cooperate and were among the first to declare war against the Axis. By contrast, Argentina adamantly resisted any efforts by the United States to dictate its wartime policies. Thus, the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor and the subsequent entry of the United States into World War II prompted the State Department to anxiously confirm the support of its Latin American counterparts.

Wartime Detention

In January 1942, delegates to the Third Meeting of the Foreign Ministers of the American Republics agreed to break off diplomatic relations with the Axis and called for the "detention and expulsion of dangerous Axis aliens" from the Western Hemisphere. The United States sought to protect its strategic interests, most notably the Panama Canal. Central American governments with the closest ties to the United States were the first to round up Axis nationals for deportation. The United States had interests in Bolivia's supply of tin, tungsten, and rubber, which may explain why Bolivia deported nearly one–sixth of its Japanese population. Yet not all countries were eager to participate. Chile, which feared a Japanese attack and did not break relations with Japan until 1943, did not intern its Japanese population of approximately 1,000. Argentina, the last Latin American country to break diplomatic relations with the Axis, did not intern its Japanese population of 6,000. [3]

Peru briefly considered developing an internment program of its own but decided to deport its Japanese to the United States instead. In April 1942, the first ship, the Etolin , left Callao with 141 Japanese males on board. According to historian C. Harvey Gardiner, nearly all of the deportees were either unmarried or had spouses in Japan. Only one deportee was a Peruvian citizen. During the course of that first trip, the Etolin picked up Japanese deportees from Colombia before heading for San Francisco, where the United States denied them visas and passports and classified them as "enemy aliens." A few of these deportees had been on the FBI's "Proclaimed List," but the vast majority were not. [4] The Japanese on this first trip likely believed that they had signed up for repatriation to Japan, not internment in the United States.

Subsequent trips by the Gripsholm , the Shawnee , and the Frederick C. Johnson transported Japanese Peruvians from Peru to Panama before heading to the United States. The ships docked at New Orleans and the Japanese deportees were taken by train to internment camps in Texas. The last sailing of the Frederick C. Johnson , which departed Peru in October 1944, carried twice as many women and children as adult men, a stark contrast from the Etolin’s first trip. These "voluntary internees," so the women were called, had hoped to reunite with their families in the United States. [5]

With little recourse under the United States Constitution, Japanese Latin Americans lodged their complaints with the Spanish Embassy, the designated "protecting power" for the Japanese in the United States. Many of the requests, especially later in the war, concerned the reunification of families. The Justice Department had originally sent males to Santa Fe and Kenedy and females to Seagoville. Crystal City was known as the "family internment camp," and in 1948, was the last of the camps to close. The material conditions at INS camps varied, and in some cases were better than those at War Relocation Centers. Nevertheless, the fact remained that the Japanese Latin Americans were held indefinitely without charge in a foreign country.

Peru's decision to cooperate with the United States during World War II was a result of President Manuel Prado's calculated efforts to cultivate favor at home and abroad. By riding the wave of anti-Japanese animus in Peru, Prado fostered a lucrative wartime relationship with the United States, a country eager to find allies in its bid to bolster its hemispheric defense. As historian Daniel M. Masterson has found, Peru secured American loans to finance its first steel processing plant during World War II, and was among the leading recipients of lend-lease aid in South America. In exchange, Peru permitted the United States to operate an air base at Talara, a strategic location that U.S. officials had hoped would defend against sea-borne attacks to the Panama Canal. [6]

Other Latin American countries with a large Japanese population devised alternatives to the deportation-internment program. In the wake of Pearl Harbor, Mexico broke its diplomatic ties to Japan and ordered the evacuation of all Japanese within 200 kilometers of the Pacific coast and 100 kilometers of the United States-Mexico border to either Mexico City or Guadalajara. By concentrating Japanese in urban areas, the government had hoped to more carefully monitor the activities of its approximately 5,100 Japanese residents. The Japanese in Mexico were not interned and relatively few were sent to the United States for that purpose. Mexican leaders were especially mindful of their country's political and historical relationship to the United States, a country that had seized one–third of Mexico's territory as a result of the U.S.-Mexico War. [7]

In Brazil, the large number of Japanese and the critical role that they played in the agricultural economy rendered cooperation with the United States' deportation-internment program logistically infeasible. Nearly 250,000 Japanese resided in Brazil, according to the 1940 census, and the vast majority worked as farmers producing staples such as rice, cotton, sugar, fruits, vegetables and silk. Nevertheless, Brazil took measures to monitor its Japanese population by banning Japanese language and texts. According to oral histories conducted by scholar Sayaka Funada-Classen, the police searched the houses of Japanese residents, stole property, and in some cases, resorted to violent beatings. The Japanese were not interned but in July 1943, the government relocated approximately 4,000 Japanese to Paranaguá from the Santos-São Paulo area. Japanese from Pará, moreover, were relocated to Tomé-Açu. [8]

After the War

In 1945, delegates to the Mexico City Conference on the Problems of War and Peace agreed that "any person whose deportation was necessary for reasons of security of the continent" should be prevented from "further residing in this hemisphere if such residence should be prejudicial to the future security or welfare of the Americas." In the United States, President Harry Truman issued a Presidential Proclamation in September that authorized the removal from the Western Hemisphere of enemy aliens "who are within the territory of the United States without admission under the immigration laws." [9] Most of the Japanese Latin Americans, therefore, were forced to leave.

Between November 1945 and June 1946, more than 900 Japanese Peruvians repatriated to Japan. Among those who repatriated was Kimiko Saeki Matsubayashi, the daughter of a former automobile body parts manufacturer in Peru. Kimiko lived in Lima until she and her family were deported to the United States and interned at Crystal City in March 1944. After the war, Kimiko's father decided to return to Japan. The family found temporary housing in an old school building, sold their belongings, and readjusted to life in a war-devastated country. [10]

Some Latin American countries permitted their Japanese deportees to return but Peru refused to accept responsibility for its participation in the deportation-internment program. The first few Japanese Peruvians to return in November 1945, faced a hostile environment. The sensationalist newspaper, Mundo Grafico , disparaged them as the "leaders of the Japanese Fifth Column." No more than 80 Japanese Peruvians came back and only those with Peruvian citizenship were permitted to enter. [11] Peru continued to prohibit Japanese immigration well into the 1950s.

Meanwhile in the United States, several hundred Japanese Peruvians managed to stay despite President Truman's Presidential Proclamation. In 1946, Wayne M. Collins and A.L. Wirin , attorneys with the American Civil Liberties Union , helped 364 Japanese Peruvians obtain "parole" at Seabrook Farms , a truck farming plant in New Jersey. They worked as undocumented immigrants until a change in immigration law in 1952. Arturo Shibayama, a former internee, later recounted his long path to United States citizenship in the documentary film, Hidden Internment: The Art Shibayama Story . [12]

In the decades following the war, Japanese Latin Americans worked with scholars and activists to find out why they had been targeted during World War II. Michi Weglyn , a Japanese American who had been incarcerated at the Gila River War Relocation Center, suggested in her 1976 book, Years of Infamy , that the Japanese Latin Americans had been "kidnapped." [13] Nevertheless, the United States refused to accept responsibility, placing the blame instead on countries like Peru. Largely excluded from the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which granted Japanese Americans redress and an apology from the government for their incarceration during World War II, Japanese Latin Americans mounted a campaign in the 1990s and 2000s to educate the broader public about their own wartime experiences.

In 1996, former internees and their families formed a group called the "Campaign for Justice" to promote their cause. Between 1996 and 1999, five lawsuits were filed on behalf of the Japanese Latin Americans. The class action lawsuit, Mochizuki, et al. v. USA , resulted in a settlement whereby the United States government agreed to issue an individual letter of apology and to pay each internee $5,000. In 2007, U.S. Representatives Xavier Becerra (D-CA), Daniel Lungren (R-CA), and Mike Honda (D-CA) along with U.S. Senator Daniel Inouye (D-HI) introduced the "Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Latin Americans of Japanese Descent Act," a bill currently under consideration by Congress. [14]

For More Information

Friedman, Max Paul. Nazis and Good Neighbors: The United States Campaign Against the Germans of Latin America in World War II . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Gardiner, C. Harvey. Pawns in a Triangle of Hate: The Peruvian Japanese and the United States . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1981.

Higashide, Seiichi. Adios to Tears: The Memoirs of a Japanese-Peruvian Internee in U.S. Concentration Camps . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000 [1993].

Mak, Stephen. "America's Other Internment: World War II and the Making of Modern Human Rights." Ph.D. diss., Northwestern University, 2009.

Masterson, Daniel M. with Sayaka Funada-Classen. The Japanese in Latin America . Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Footnotes

- ↑ U.S., Department of State, Publication 1983, Peace and War: United States Foreign Policy, 1931-1941 (Washington, D.C.: U.S., Government Printing Office, 1943), 438-39.

- ↑ Daniel M. Masterson, with Sayaka Funada-Classen, The Japanese in Latin America (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2004), 118-119.

- ↑ Masterson, 140-147.

- ↑ C. Harvey Gardiner, Pawns in a Triangle of Hate: The Peruvian Japanese and the United States (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1981), 27-28.

- ↑ Gardiner, 26-29.

- ↑ Masterson, 159.

- ↑ Ibid., 126.

- ↑ Ibid., 132.

- ↑ Presidential Proclamation 2662 (8 September 1945), see Code of Federal Regulations , title 3, p. 65 (1943-1948).

- ↑ Masterson, 172.

- ↑ Ibid., 176.

- ↑ Ibid., 174-175.

- ↑ Michi Weglyn, Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America's Concentration Camps , (New York: Morrow Quill Paperbacks, 1976).

- ↑ For information regarding the "Campaign for Justice," see "Campaign for Justice: Redress Now for Japanese Latin American Internees!" Accessed 11 September 2011, http://www.campaignforjusticejla.org .

Last updated April 18, 2017, 9:06 p.m..

Media

Media