A.L. Wirin

| Name | A. L. Wirin |

|---|---|

| Born | April 11 1900 |

| Died | February 4 1978 |

| Birth Location | Russia |

Civil rights lawyer who worked on a wide variety of Japanese American cases during and after World War II. As an attorney for the Southern California branch of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) during World War II, A.L. Wirin was involved in the key Japanese American wartime cases, arguing the Korematsu and Yasui cases before the Supreme Court. As chief counsel for the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) during and after the war, he worked on many landmark civil rights-related cases, involving issues such as the alien land laws , restrictive housing covenants , and segregated schools. He also worked with wartime draft resisters and successfully represented dozens of "strandees," Japanese Americans caught in Japan during the war, many of whom had lost their American citizenship due to service in the Japanese military or voting in Japanese elections.

Before the War

A.L. Wirin was born to a Jewish family in Russia on April 11, 1900 (some sources say 1901), and migrated with his parents and two siblings to the United States circa 1908. The family eventually settled in an immigrant neighborhood in Boston, where two more children were born. Once in the U.S., he was named Abraham Lincoln Wirin, a name he disliked; he went by his initials or by "Al" throughout his life.

As a child, he sold milk and delivered newspapers, while also excelling in school. According to one obituary, Wirin began his civil liberties career as a Boston schoolboy defending women and children in a peace march against assaults by sailors. He was arrested and fined $5. He attended Harvard University, supporting himself in part by tutoring football players, and managed to finish his studies in three years. After graduating cum laude, he attended Harvard Law School for a year, then transferred to Boston University Law School. There he received his law degree in 1925. After a stint as a bankruptcy lawyer, he moved to New York, where he was hired as staff layer for the American Civil Liberties Union. After stints in other cities, he settled in Los Angeles, where he set up a private law office, working in bankruptcy law. In 1933, Wirin became a full-time staff lawyer for the Southern California ACLU. Much of his time was devoted to labor issues. In a well-publicized 1934 incident, Wirin was abducted by vigilantes, including highway patrol officers, during a trip to address Mexican farm workers in Imperial County, California, who were attempting to organize. In what one historian described as "like a scene right out of the movie The Godfather ," Wirin was beaten, robbed, and left stranded in the desert. Later in the decade, Wirin established a private practice, with Leo Gallagher as partner. The firm specialized in labor law, and was on retainer with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Wirin was most visible as attorney for controversial CIO leader Harry Bridges. [1]

Challenges to Exclusion

Although A.L. Wirin participated in struggles for racial justice during the prewar era, most notably through his collaboration with Loren Miller in lawsuits challenging restrictive covenants, he had little contact with Japanese Americans. Nevertheless, he was outraged by the exclusion and subsequent incarceration of West Coast Japanese Americans during World War II. In February 1942, shortly after President Roosevelt authorized exclusion, Wirin testified against it before the Tolan Committee , stating in part, "We feel that treating persons because they are members of a race constitutes illegal discrimination, which is forbidden by the fourteenth amendment whether we are at war or peace." [2] Eager to find a test case with the goal of taking it to the Supreme Court, he agreed to defend Ernest and Toki Wakayama when they came to the SC-ACLU in April 1942 seeking to challenge their confinement . Due to Ernest's status as a World War I veteran, American Legion officer, and outspoken patriot, Wirin thought he had an ideal petitioner. His acceptance of the case would cost Wirin heavily. Warned by leaders of the CIO, his most important client, to choose between their unquestioning support of the war effort and his civil liberties work, he resigned from his firm and opened a solo law practice. [3] Joining forces with attorney Hugh Macbeth , he filed a habeas corpus petition on the Wakayamas' behalf in federal court in August 1942 (the delay in action being caused by Wirin's need to wind up his previous law practice). However, the court declined to act on the petition until February 1943, when a three-judge panel scheduled a hearing. By that time, the Wakayamas' anger at their treatment at Manzanar led them to request "repatriation" to Japan, and Wirin reluctantly withdrew the case. [4] In 1944-45, he challenged military exclusion from the West Coast once more when he represented George Ochikubo and two other Nisei, who challenged their "individual exclusion," although the case of Ochikubo v. Bonesteel was not resolved before the and of the war and the lifting of all restrictions on Japanese American residence. [5]

Meanwhile, he also began work as counsel for the JACL. While the JACL initially opted not to support the test cases against mass removal, it did endorse the habeas corpus suits of the Wakayamas and of Mitsuye Endo . In November 1942, Wirin was invited to the JACL Special National Conference in Salt Lake City, where he reported on the progress of Wakayama . He also reported on the case of Regan v. King , an attempt by nativist groups in California to strip Nisei of their citizenship that was being prepared for argument before the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. On Wirin's recommendation, the JACL filed an amicus brief in the Regan case that was anonymously authored by anthropologist Morris Opler , soon to become community analyst at Manzanar , and by Hugh Macbeth. Wirin received permission to argue before the Appellate court on behalf of the JACL. In the end, the case was dismissed before he could present his argument. Following his actions in Regan , Wirin became increasingly active on behalf of Japanese Americans. First, in 1943 he was tapped by Roger Baldwin to argue the Korematsu case before the U.S. Supreme Court, in a hearing narrowly focused on the question of whether Fred Korematsu could appeal his probationary sentence. (He was not part of the legal team on the later and more substantive Korematsu hearing in 1944.) Meanwhile, Wirin shared time with Earl Bernard in arguing the Yasui case before the Supreme Court. When the Hirabayashi and Korematsu cases went to the Supreme Court, Wirin arranged for the submission of amicus briefs, both again drafted by Opler, on behalf of the organization. Wirin reported for the JACL newspaper Pacific Citizen on the Supreme Court arguments in those cases. [6]

Despite criticism from JACL leaders, Wirin also stood up for Nisei civil rights when he represented the leaders of the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee (FPC) against charges of conspiracy in counseling Nisei to resist the draft. After the war, he was among those who successfully petitioned President Harry S. Truman for amnesty for convicted resisters of conscience, which included both the FPC leaders and the convicted draft resisters. Wirin appeared as a witness before the amnesty board. [7]

In addition to his legal work, Wirin supported Japanese American by different means. He authored regular columns on the progress of the civil rights cases for the Pacific Citizen and The Open Forum , the SC-ACLU bulletin. He also participated in a number of live and radio broadcast debates during the war, in which he defended the civil rights of Japanese Americans and endorsed their return to the Pacific Coast.

Renunciant and Strandee Cases

In the aftermath of the war, Wirin played an active role in the renunciation cases stemming from the segregation of Japanese American camp inmates at Tule Lake . In the last months of the war, following enactment of a new statute sponsored by the U.S. Justice Department to facilitate renunciation of citizenship, over 5,000 Nisei in the frenzied environment of the "segregation center" had renounced their citizenship. Facing deportation after the war, many sought to have their renunciations canceled. Wirin's fellow ACLU attorney Wayne M. Collins , with whom Wirin frequently clashed over both principles and strategy in Japanese American matters, took up the vast majority of renunciant cases. In contrast, Wirin's attempts to secure renunciant clients were initially in vain, due in large part to his ties to the JACL and unpopularity of that organization at Tule Lake. He did eventually secure four clients from Tule Lake, and was able to have their renunciations voided through legal action. In the case of Murakami v. Acheson (1949), the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals cancelled the renunciations.

Wirin's role in the renunciant cases would become his most controversial within the Japanese American community. Wirin took the position that duress from hostile inmate pressure groups was the primary reason that the renunciations were invalid. In contrast, Wayne Collins attempted to get the deportations reversed via a mass lawsuit charging that governmental actions were the primary cause of duress. Collins later complained that Wirin's victories had the effect of undercutting his own efforts, forcing him to spend the next twenty years seeking individual justice for the thousands of renunciants and making it more difficult to recover their lost citizenship. It is uncertain how much validity there is to Collins's charges, which have been repeated by later scholars. [8] Conversely, Collins further charged that Wirin's actions were part of a conspiracy tied to the ACLU's larger strategy of downplaying official injustice in the renunciant cases, in order to maintain positive relations with the federal government. Such an accusation seems exaggerated in view of Wirin's independent-mindedness, as demonstrated by his defense of draft resisters, and his challenges to official authority.

Wirin and several other lawyers, with the support of the JACL, meanwhile intervened on behalf of 30 Issei "hardship cases" who were threatened with involuntary deportation, and won them stays. He and his law partner Fred Okrand also took on dozens of "strandee" cases in the 1950s; these generally involved Nisei who had been stranded in Japan during and after the war who either were forcibly conscripted into the Japanese armed forces or who voted in Japanese elections, either of which resulted in an automatic loss of American citizenship. He and Okrand—often joined by Hawai'i Nisei lawyer Katsuro Miho in cases involving residents of Hawai'i—were generally able to have citizenship restored to these individuals by arguing that the military service came under duress and that the voting had been encouraged by the American occupation government. For example, in the case of Henry Yada, who had been stranded in Japan in 1941, Wirin persuaded the court that Yada had voted because he feared what would happen if he did not vote in elections sponsored by the U.S. Army of occupation. [9] With his partners, he also represented Japanese Americans seeking the return of deposits in American branches of Japanese banks that had been seized during the war. [10]

Postwar Civil Rights Cases

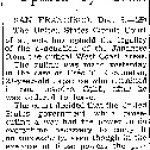

In the period following World War II, Wirin continued his close association with Japanese Americans. He invited Nisei lawyer John Maeno to join his law office, and hired Frank Chuman as his associate. In 1946, he invited former JACL president Saburo Kido to be his law partner. Meanwhile, he continued his work as JACL chief counsel. Working with the JACL's Anti-Discrimination Committee , Wirin and Okrand took part in several landmark suits that broke down various discriminatory barriers faced by Japanese Americans. First, Wirin and Okrand defended numerous Japanese American clients facing escheat suits launched by the state of California to take away their land under the Alien Land act. In 1945, together with Hugh Macbeth, Wirin took up the defense of Fred and Kajiro Oyama in an escheat suit, and he ultimately led the team that challenged California's Alien Land Act before the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court's ruling in Oyama v. California (1948) halted the wave of escheat suits that California had brought to strip Japanese Americans of their land and led to the demise of the Alien Land Act soon after. Similarly, Wirin brought a test case on behalf of Torao Takahashi to challenge California's ban on commercial fishing licenses for Issei , and again directed the JACL legal team in argument before the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court's ruling in Takahashi v. California Fish and Game Commission (1948) struck down all legal discrimination against "aliens ineligible to citizenship". Wirin himself later told Frank Chuman in a 1971 interview that he considered the Oyama and Takahashi cases the most important ones he had ever handled, because of their role in shaping the Supreme Court's "strict scrutiny" doctrine in civil rights cases. On behalf of the JACL, he and Kido also filed an amicus brief in the Mendez v. Westminster case in 1946–47, a school segregation case involving Mexican Americans that represented the first time JACL intervened in a civil rights case that did not directly involve Japanese Americans. He also represented the JACL as part of a multi-ethnic coalition opposing restrictive covenants, and that played a role in the landmark Supreme Court ruling Shelley v. Kraemer (1948), which halted legal enforcement of such covenants. [11]

Later Career

Even after resigning as JACL Chief Counsel in 1949-50, Wirin continued his work for the ACLU. He represented accused Communists during the McCarthy era, causing him to be branded a Communist. He replied, "If being counsel for a Communist makes one a Communist I deserve equally all of the following titles: Nazi, Anarchist, Trotskyite, Socialist, Republican, Democrat and capitalist." [12] Among his other well-known clients were death row inmate Caryl Chessman, political agitator Gerald L.K. Smith, and journalist John W. Powell. As part of his defense of Powell, accused of sedition for printing charges about American germ warfare against North Korea, Wirin was the first American to receive a state department passport with a visa to travel to the People’s Republic of China. In 1968, Wirin organized the legal defense team of Sirhan B. Sirhan, who was charged with the assassination of Senator Robert F. Kennedy. In 1972, Wirin was forced to retire following a heart attack. He died of another heart attack six years later, on February 4, 1978.

While A.L. Wirin's work on behalf of Japanese Americans was widely reported at the time, both in the Japanese American press and in outside media, it is little known today, in contrast to that of his frequent rival Wayne M. Collins. Wirin's wartime defense of Nisei citizenship required not only a willingness to work and attachment to democratic principle but considerable bravery. He received death threats "because he is a white man and because he is a Jew." [13] His postwar challenges to the Alien Land Act and to discriminatory fishing laws led not only to major victories for Japanese Americans but to landmark Supreme Court civil rights precedents. Conversely, unlike Collins, it must be said that Wirin's efforts on behalf of Japanese Americans brought him a financial windfall, in the form of lawyer's fees for claims against the government under the 1948 Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act and its extensions. In 1960 he stated in an interview, "It is to them [Japanese American clients] that I owe my fine office and living today." [14]

For More Information

Collins, Donald E. Native American Aliens: Disloyalty and the Renunciation of Citizenship by Japanese Americans During World War II . Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1985.

Irons, Peter. Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases . New York: Oxford University Press, 1983. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Kutulas, Judy. The American Civil Liberties Union and the Making of Modern Liberalism . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Muller, Eric L. Free to Die for Their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters in World War II . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

———. American Inquisition: The Hunt for Japanese American Disloyalty in World War II . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Oliver, Myrna. "Al Wirin, First Full-Time ACLU Lawyer, Dies at 77." Los Angeles Times , Feb. 5, 1978, 3.

Robinson, Greg. After Camp: Portraits in Midcentury Japanese American Life and Politics . Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

Takei, Barbara. "Legalizing Detention: Segregated Japanese Americans and the Justice Department's Renunciation Program." Journal of the Shaw Historical Library 19 (2005): 75–105. https://archive.org/details/questionofloyalt00shaw

Footnotes

- ↑ Biographical sketch from Peter Irons, Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983 and Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 110–11; Myrna Oliver,"Al Wirin, First Full-Time ACLU Lawyer, Dies at 77," Los Angeles Times , Feb. 5, 1978, 3; Alice Sumida, "Civil Rights Defender," Pacific Citizen , January 24, 1948, 2; James Gray, "The American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California and Imperial Valley Agricultural Labor Disturbances: 1930, 1934" (Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, 1966), 70–78; Leah Fernandez, "Race and the Western Frontier: Colonizing the Imperial Valley, 1900–1948 (Ph.D dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2012) 163–68. Quote from the last, p. 163.

- ↑ Roger Daniels, Concentration Camps, U.S.A.: Japanese Americans and World War II (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971), 78.

- ↑ Samuel Walker, In Defense of American Liberties: A History of the ACLU (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 142; Greg Robinson, After Camp: Portraits in Midcentury Japanese American Life and Politics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 178–79.

- ↑ Irons, "Justice at War , 114–15; Robinson, After Camp , 78–79.

- ↑ Eric Muller, American Inquisition: The Hunt for Japanese American Disloyalty in World War II (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 107–33;

- ↑ Irons, "Justice at War , 192–94, 222–27; Greg Robinson, A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in North America. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 112.

- ↑ Eric Muller, Free to Die for Their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters in World War II (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 114–24.

- ↑ See for example Donald Collins, "Native American Aliens: Disloyalty and the Renunciation of Citizenship by Japanese Americans during World War II (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1985), 123–44 and Barbara Takei, "Legalizing Detention: Segregated Japanese Americans and the Justice Department's Renunciation Program," Journal of the Shaw Historical Library 19 (2005), 96–97.

- ↑ Pacific Citizen , Nov. 20, 1948, 2, June 23, 1951, 2. The Pacific Citizen in this period is filled with accounts of many similar cases; see for instance March 6, 1953, 3; Nov. 27, 1953, 1; Sept. 3, 1954, 11.

- ↑ Though the U.S. government agreed to repay the seized yen deposits after the war, it opted to do so at the postwar exchange rate, which was exponentially lower than the prewar rate. The case, which sought to have claimants repaid at the prewar rate, ultimately was decided in favor of the depositors, but not until 1967, by which time many had long since died. Audrie Girdner and Anne Loftis, The Great Betrayal: The Evacuation of the Japanese-Americans during World War II (Toronto: Macmillan, 1969), 437–38.

- ↑ Robinson, After Camp, 131–32, 195–216; "Interview of Al Wirin 12-71, Los Angeles, CA," Frank Chuman Papers, Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA, Box 534, Folder 17. In addition to representing the Oyamas, he and his associates represented many of the other Issei/Nisei families targeted in escheat suits filed by the state of California in 1944–46.

- ↑ Oliver, "Al Wirin," 3.

- ↑ Fred Fertig, "Open Letter to the Nisei," Pacific Citizen , Dec. 21, 1946, 37.

- ↑ Quote from Murray Fromson, "Abraham Lincoln Wirin Has Crowded Law Career as Defender of Causes," Joplin Globe , Feb. 12, 1960, 8C

Last updated Dec. 15, 2023, 6:32 a.m..

Media

Media