Office of Redress Administration

Federal agency created by the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 charged with identifying and verifying Japanese Americans eligible for monetary redress and for processing their payments and apology letters. Over its ten-year life, the Office of Redress Administration (ORA) worked with Japanese American community groups to arrange for the payment of 82,264 redress recipients. While ORA staff were almost uniformly praised by Japanese American groups for their effective and sensitive approach, the ORA and the Justice Department were also criticized for denying redress to some seemingly deserving groups.

The ORA formed within the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice soon after the signing of the Civil Liberties Act on August 10, 1988, hiring staff and opening offices within a month. Bob Bratt, a young executive officer in the Civil Rights Division, was tapped to be the ORA's first director by early September and a main office set up in Washington, D.C. The ORA opened a satellite office in San Francisco in October. The Civil Liberties Act specified that the ORA was to have a ten-year life to complete its work, which limited its ability to attract federal employees as it built its staff. About one hundred people worked for the ORA at its peak, all contractors beside perhaps ten to fifteen being government employees. The ORA staff was noted for its diversity and included many Japanese Americans as well as African Americans and other Asian Americans. [1]

While setting up its offices, the ORA focused initially on research and on building ties to the Japanese American community. ORA staff visited the National Archives and began creating a database of inmates using War Relocation Authority records and the magnetic tape of Form WRA-26 punch card data. "I hired two students who sat in front of a computer and entered war records all day long, basically," recalled Joanne Chiedi, the deputy director of the Verification Unit. Recognizing that "rightfully so, [for] many people in the community, the government wasn't their favorite group," Bratt set out to built connections with Japanese American organizations, ultimately focusing on the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) and National Coalition for Redress/Reparations (NCRR). He recalled that "in the first year, I was nonstop going back and forth to the West Coast to meet with community groups." ORA staff traveled to areas with significant Japanese American populations to hold workshops at which they could disseminate information on the redress program and meet community members, often coordinating with JACL or NCRR. The ORA also created a bilingual phone hotline. [2]

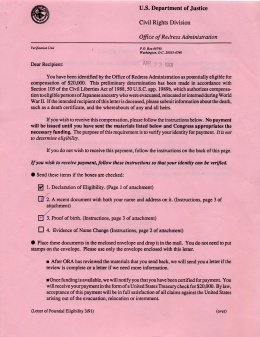

By mid-November, the ORA had gathered some 30,000 names of eligible persons out of an anticipated 60,000 and over 48,000 by the spring of 1989. Because the Civil Liberties Act only authorized redress payments but did not appropriate funding for them, separate appropriations had to be secured from Congress. The Fiscal Year 1990 budget allotted only $20 million for redress payments, only 1.6% of the amount authorized, enough to pay only 1,000 people. The appropriations issue was later resolved largely through the efforts of Senator Daniel Inouye , turning redress into an entitlement program that didn't have to fight for annual appropriations. Prioritizing the oldest living recipients, the ORA put together a ceremony in Washington, D.C. on October 9, 1990, at which U.S. Attorney General Dick Thornburgh presented redress checks to the first nine recipients, the eldest of whom was 107 year old Rev. Mamoru Eto. The ORA set up similar ceremonies in West Coast cities. Over 20,000 people born before July 1, 1920 were paid that October. In October 1991, another 22,800 born in 1927 or earlier were paid. [3]

With the payment process proceeding, Bratt left the ORA in 1992 and was replaced by Paul Suddes (1992–94) then by Irva "DeDe" Greene (1994–98). Deserene Worsley served as acting administrator, June to Oct. 1994. [4]

Much of the second half of the ORA's history focused on the relatively small number of redress claims that it had initially denied. These cases fell into a wide variety of categories, including Japanese Latin Americans , children of " voluntary evacuees ," and minor children who had gone to Japan with their families, among many others. There were also over twenty different areas in Hawai`i where Japanese Americans were excluded from their homes, but not incarcerated. Working with NCRR, JACL and other community groups on the one hand and with Justice Department officials on the other, the ORA was able to approve many of these disputed groups for redress, though denying others. In some cases, where written documentation did not exists, the ORA was able to successfully approve redress claims based on affidavits by contemporaneous witnesses. There were also some thirty lawsuits filed by those who had been found ineligible. [5]

For the most part, Japanese Americans viewed the ORA favorably and came to see their staff as allies in their quest for redress. Kay Ochi, one of the leaders of NCRR, praised the ORA for coming to the community and calling the staff "really good people, meaning compassionate, they were all so professional, they cared so much about their job." Redress movement chroniclers Mitchell T. Maki, Harry H.L. Kitano, and S. Megan Berthold wrote that "[m]any community activists agreed that the ORA and its leadership brought a sympathetic openness to the interpretation of the legislation." The Hawai`i Herald wrote of the ORA's "caring administrators" who have "performed a tremendous service to the AJA community." Bratt was honored by a coalition of community groups in Northern California when he left the ORA in April 1992 and by the Honolulu JACL in 2008. [6]

As the ORA's sunset date in 1998 approached, it continued to try to identify the roughly 3,000 still unfound eligible persons, working with Japanese community newspapers to circulate their names. A settlement on a lawsuit filed by Japanese Latin Americans resulted in smaller $5,000 reparations payments in the last months of the ORA. The ORA's closing date was eventually extended 180 days, to February 5, 1999. A small amount of supplemental funding in the summer of 1999 allowed the ORA to pay out a few more claims. [7]

In total, the ORA processed 84,762 cases to completion and paid 82,264 of them, over 20,000 more than first anticipated. Of the rest, 1,581 were found to be ineligible, 390 were deceased with no heirs, 541 were Japanese Latin Americans who were ineligible, and thirty refused to accept payment.

Of those awarded redress, 71,946 had been incarcerated in WRA concentration camps, with others being those in Justice Department or army internment camps, Hawai`i cases, "voluntary evacuees," and those in other categories. [8]

For More Information

Maki, Mitchell T., Harry H.L. Kitano, and S. Megan Berthold. Achieving the Impossible Dream: How Japanese Americans Obtained Redress . Forewords Robert T. Matsui and Roger Daniels. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999.

Nikkei for Civil Rights and Redress. NCRR: The Grassroots Struggle for Japanese American Redress and Reparations . Los Angeles: UCLA Asian American Studies Center Press, 2018.

Office of Redress Administration (ORA) Oral History Project in Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-1020/ .

The Office of Redress Administration (ORA) Oral History Project, https://japaneseamericanredress.org/ .

Footnotes

- ↑ Mitchell T. Maki, Harry H.L. Kitano, and S. Megan Berthold, Achieving the Impossible Dream: How Japanese Americans Obtained Redress (forewords Robert T. Matsui and Roger Daniels, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999), 199; Karleen Chinen, "Redress—The Next Step," The Hawai`i Herald , Nov. 18, 1988, 1; Lisa Johnson interview by Emi Kuboyama, Alexandria, Virginia, May 19, 2019, Segment 6 and 7, Emi Kuboyama, Office of Redress Administration (ORA) Oral History Project Collection, Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1020/ddr-densho-1020-3-transcript-e6bfa19be2.htm ; Angela Noel Gantt interview by Emi Kuboyama, Washington, D.C., May 20, 2019, Segment 6, Emi Kuboyama, Office of Redress Administration (ORA) Oral History Project Collection, Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1020/ddr-densho-1020-4-transcript-61fa2dcf81.htm .

- ↑ Robert "Bob" Bratt interview by Emi Kuboyama, San Francisco, California, Aug. 19, 2019, Segments 7 and 8, Emi Kuboyama, Office of Redress Administration (ORA) Oral History Project Collection, Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1020/ddr-densho-1020-6-transcript-6c988a9910.htm ; Joanne Chiedi interview by Emi Kuboyama, Washington, D.C., May 20, 2019, Segment 1, Emi Kuboyama, Office of Redress Administration (ORA) Oral History Project Collection, Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1020/ddr-densho-1020-5-transcript-39ac7efd3a.htm ; Nikkei for Civil Rights and Redress, NCRR: The Grassroots Struggle for Japanese American Redress and Reparations (Los Angeles: UCLA Asian American Studies Center Press, 2018), 274–75.

- ↑ Chinen, "Redress—The Next Step"; Maki, et al., Achieving the Impossible Dream , 199–200; Pacific Citizen , Oct. 12, 1990, 1; Kay Ochi interview bu Emi Kuboyama, San Diego, California, Jan. 24, 2020, Segment 8, Emi Kuboyama, Office of Redress Administration (ORA) Oral History Project Collection, Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1020/ddr-densho-1020-10-transcript-9869a9aa1a.htm ; The Hawai`i Herald , June 7, 1991, A-4 and Oct. 18, 1991, A-4.

- ↑ Maki, et al., Achieving the Impossible Dream , 272–73fn45.

- ↑ Kay Ochi interview, Segment 10; William "Bill" Kaneko interview by Emi Kuboyama, Honolulu, Hawaii, Dec. 30, 2019, Segment 5, Emi Kuboyama, Office of Redress Administration (ORA) Oral History Project Collection, Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1020/ddr-densho-1020-11-transcript-72683bfb4f.htm ; Tink Cooper interview by Emi Kuboyama, Washington, D.C., Sept. 11, 2019, Segment 3, Emi Kuboyama, Office of Redress Administration (ORA) Oral History Project Collection, Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1020/ddr-densho-1020-7-transcript-2d061bf5c2.htm . For a full list of categories that were initially denied and their ultimate outcomes, see NCRR: The Grassroots Struggle , 277–85.

- ↑ Kay Ochi interview, Segment 12; Maki, et al., Achieving the Impossible Dream , 199; The Hawai`i Herald , Oct. 2, 1992, A-18, Jan. 3, 1997, E-1 and Feb. 15, 2008, 13.

- ↑ Mark Santoki, "Office of Redress Closing Shop," The Hawai`i Herald , Jan. 3, 1997, E-1; Kay Ochi, "Remembering the Post-CLA Redress Work," in NCRR: The Grassroots Struggle , 290; Julie Small, "Hundreds May Lose Redress," The Hawai`i Herald , Jan. 22, 1999, A-11; NCRR: The Grassroots Struggle 311.

- ↑ NCRR: The Grassroots Struggle , 310.

Last updated Jan. 28, 2022, 12:03 a.m..

Media

Media