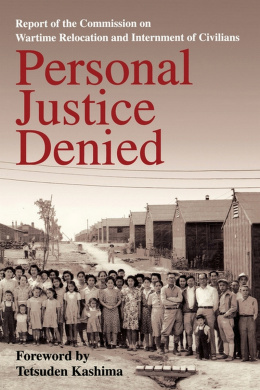

Personal Justice Denied (book)

| Title | Personal Justice Denied |

|---|---|

| Author | Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians |

| Original Publication Date | 1983 |

| Pages | 467 pages |

The 467-page report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) concluding that Executive Order 9066 was not justified by military necessity but rather was the result of "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership." Based on its conclusions and supporting documentation, the 100th Congress adopted H.R. 442 which was signed into law as the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 , granting $20,000 in monetary reparations and a public apology to all those whose Constitutional rights had been violated as a result of the wartime exclusion.

Background

A commission to "review the facts and circumstances surrounding Executive Order 9066" and the "directives of the United States military forces" requiring the incarceration was signed into law by President Jimmy Carter on July 31, 1980. [1] After twenty days of public hearings and eighteen months of thorough investigation by a commission staff headed by special counsel Angus Macbeth, the findings of the nine-member Commission on the Wartime Internment and Relocation of Civilians were published on February 24, 1983, as Personal Justice Denied . On June 16, 1983, further Recommendations were issued; a third publication, Papers for the Commission , appeared later that year discussing the intercepted Japanese diplomatic cables, code-named MAGIC . In 1997 the original two-volume report by the U.S. Government Printing Office was published by The Civil Liberties Public Education Fund and the University of Washington Press, with an added prologue and a new foreword by University of Washington professor Tetsuden Kashima.

Summary

The major conclusions reached in the report were that Executive Order 9066 was "not justified by military necessity, and the decisions which followed from it—exclusion, detention, the ending of detention and the ending of exclusion—were not founded upon military conditions." Rather, the causes were "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership." [2] It also concluded that a "grave personal injustice was done. . . without individual review or any probative evidence." [3]

What led to the decision to exclude citizens of Japanese ancestry and enemy aliens is covered in Part I of Personal Justice Denied , with an examination of their status pre-World War II, how the decision was implemented, and the effects of that decision, including economic loss, "assembly center" and "relocation center" conditions, and questions of loyalty. It also deals with the decision to end exclusion, and finally, draws comparisons with the historical treatment of persons of Japanese ancestry living in Hawai'i and German Americans who were not excluded. Part II deals specifically with the detention of Aleuts in the Aleutian and Pribilof Islands.

As to those surviving individuals of Japanese ancestry who were incarcerated, Part III consists of five recommendations made by the commission as remedies: (1) that Congress recognize the injustice and offer an apology; (2) that the President pardon those convicted of violations based on curfew violations and review other wartime convictions based on race or ethnicity; (3) that agencies review applications for restitution of position, status or entitlements lost during wartime; (4) that Congress appropriate monies for a special fund for research and public education; and (5) that Congress appropriate $1.5 billion to provide a compensatory payment of $20,000 each to surviving persons displaced by the wartime order. Remedies to the surviving Aleuts included individual payments of $5,000 each.

Impact

The significance of Personal Justice Denied , according to University of Washington professor Tetsuden Kashima, is threefold: (1) for its representation of the "government's own findings" in declaring the lack of military necessity, thus altering the U.S.'s long-held position on the exclusion; (2) for its sound scholarship; and (3) for its far-reaching impact on legislation, court cases, and international law. [4]

Given its status as an official governmental report, the publication of Personal Justice Denied received immediate notice by the mainstream media in the U.S. and Japan—even though many of its conclusions had been reached previously by other academicians and writers. Historian Roger Daniels noted that its conclusions were noteworthy by the fact that it prompted former Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy , one of the chief architects of the exclusion policy, to call it an "outrage." [5] Its lasting value was observed most prominently by Prof. Kashima, who stated that "almost everything written on the incarceration after 1983 refers to this report." [6]

Find in the Digital Library of Japanese American Incarceration

This item has been made freely available in the Digital Library of Japanese American Incarceration , a collaborative project with Internet Archive .

For More Information

Boehm, Randolph, ed. "Papers of the U.S. Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Part 1: Numerical File Archives." Frederick, MD: University Publications of America, Inc, 1984. http://cisupa.proquest.com/ksc_assets/catalog/1729_USCommWarRelocInternPt1.pdf . [Includes all of the documents used by the CWRIC in Personal Justice Denied .]

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians . Seattle: University of Washington Press and Washington D.C.: Civil Liberties Public Education Fund, 1997.

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians . National Parks Service. http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/personal_justice_denied/ .

Daniels, Roger, Sandra Taylor, and Harry Kitano, eds. Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988.

Hatamiya, Leslie T. Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and the Passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 . Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993.

Peter Irons, ed. Justice Delayed: The Record of the Japanese Internment Cases . Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1989.

Maki, Mitchell T., Harry H. L. Kitano, and S. Megan Berthold. Achieving the Impossible Dream: How Japanese Americans Obtained Redress . Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1999.

National Archives and Records Administration. "Check the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) for Public Hearings and Testimonies (Record Group 220)." http://www.archives.gov/research/japanese-americans/hearings.html . [Abstracts of witness testimonies and transcripts of public files.]

Tateishi, John. And Justice for All: An Oral History of the Japanese American Detention Camps . New York: Random House, 1984.

Yoshinaga-Herzig, Aiko and Marjorie Lee, eds. Speaking Out for Personal Justice: Site Summaries of Testimonies and Witnesses Registry from the U.S. Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) Hearings 1981 . Los Angeles: Civil Liberties Public Education Fund and UCLA Asian American Studies Center Press, 2011.

Footnotes

- ↑ Mitchell T. Maki, Harry H. L. Kitano, and S. Megan Berthold, Achieving the Impossible Dream: How Japanese Americans Obtained Redress (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1999), 96.

- ↑ Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (Seattle: University of Washington Press and Washington D.C.: Civil Liberties Public Education Fund, 1997), 459.

- ↑ Personal Justice Denied , 459.

- ↑ Personal Justice Denied , xix.

- ↑ Roger Daniels, Sandra Taylor, and Harry Kitano, eds., Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988), 5.

- ↑ Personal Justice Denied , xxii.

Last updated Feb. 6, 2024, 2:46 a.m..

Media

Media