Public Law 503

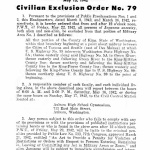

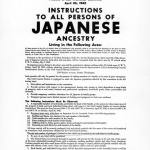

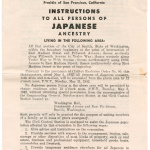

Legislation that allowed federal courts to enforce the provisions of Executive Order 9066 . Taking just twelve days to pass both sides of Congress and be signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt after its introduction on March 9, 1942, Public Law 503 specified the criminal penalties for violating military restrictions on civilians authorized by EO 9066.

Shortly after the president issued EO 9066 on February 19, 1942, attention in Washington turned towards legislation that would authorize enforcement of its provisions. Because Attorney General Francis Biddle did not feel such legislation was necessary, it was left to the War Department to draft it, a task taken up by Karl Bendetsen . By February 22, Bendetsen had sent a draft to his boss, Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy that proposed making violations a felony with penalties of up to a $5,000 fine and five years of imprisonment. Thinking Bendetsen's penalties too harsh, McCloy made violations a misdemeanor and limited the maximum prison term to one year. After the Western Defense Command issued Public Proclamation 1 on March 2, designating Military Areas 1 and 2 , Secretary of War Henry Stimson sent the draft a week later to Senator Robert B. Reynolds (D–NC), the chairman of the Senate Military Affairs Committee and to House Speaker Sam Rayburn (D–TX), along with a cover letter explaining that the proposed legislation was "to provide for enforcement in the Federal/criminal courts of orders issued under the authority of Executive Order... No. 9066." [1]

Congress moved with unusual speed. The legislation was introduced in the Senate on March 9 and in the House on March 10. The Senate Committee on Military Affairs considered the legislation on March 13 in a one hour session in which Colonel B. M. Bryan, chief of the Alien Division, Office of the Provost Marshal General , was the only one to testify. On March 17, the House Committee on Military Affairs considered it for a mere half-hour, again with Bryan providing an explanation. Both committees approved the measure unanimously. On March 19 the full Senate and full House considered the bill. The only hint of dissent in either body was the observation by Ohio Republican Senator Robert A. Taft, who stated "I think this is probably the 'sloppiest' criminal law I have ever read or seen anywhere." He added, "I have no doubt that in peacetime no man could ever be convicted under it, because the court would find that it was so indefinite and so uncertain that it could not be enforced under the Constitution." [2] Both bodies passed the measure by voice vote. It was on the president's desk by March 20 and signed into law on March 21, 1942.

For More Information

Irons, Peter. Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases . New York: Oxford University Press, 1983. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

tenBroek, Jacobus, Edward N. Barnhart, and Floyd Matson. Prejudice, War, and the Constitution . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1954.

Text of Public Law 503 from the National Archives, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/5730387 .

Last updated Feb. 1, 2024, 9:57 p.m..