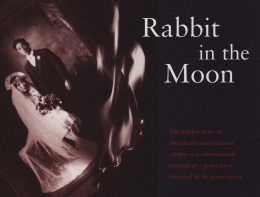

Rabbit in the Moon (film)

| Title | Rabbit in the Moon |

|---|---|

| Date | 1999 |

| Genre | Documentary |

| Director | Emiko Omori |

| Producer | Emiko Omori; Chizuko Omori |

| Writer | Emiko Omori |

| Narrator | Emiko Omori |

| Starring | Chizuko Omori (interviewee); Frank Emi (interviewee); Aiko Yoshinaga-Herzig (interviewee); Hiroshi Kashiwagi (interviewee); Harry Ueno (interviewee); James Hirabayashi (interviewee); Hisaye Yamamoto (interviewee); Shosuke Sasaki (interviewee); Ernest Besig (interviewee); Mits Koshiyama (interviewee); Frank Miyamoto (interviewee); James Omura (interviewee) |

| Music | Janice Giteck |

| Cinematography | Witt Monts; Emiko Omori |

| Editing | Pat Jackson; Emiko Omori |

| Runtime | 85 minutes |

| IMDB | Rabbit in the Moon |

Documentary film written and directed by Emiko Omori and produced by Omori with her sister Chizuko on Japanese Americans in American concentration camps during World War II that highlights resistance and other lesser told stories. Winner of many awards and screened nationally on public television in 1999, Rabbit in Moon has become one of the most acclaimed and widely viewed feature length documentaries on this topic.

Synopsis

The film is framed with the story of the Omori family. As told in Emiko's first person voice, at the time of the incarceration, she was a toddler and Chizu, ten years older, was a teenager. The seemingly happy and vibrant farming community in Oceanside, California, in which Chizu had grown up, had been replaced by the barbed wire and uncertain future of Emiko's childhood, especially after their mother's death at age thirty-four soon after leaving camp. Emiko explores the history of the forced removal and incarceration in part to learn more about the mother she barely knew. The resulting overview of the roundup and confinement highlights on-camera interviews with Chizu, who talks about the family's experience, along with interviews with key figures in the incarceration story and its aftermath. In part because the Omori family answered "no-no" on the " loyalty questionnaire ," the film comes to focus on resistance in the camps, highlighting the Manzanar riot/uprising , including an interview with Harry Ueno , one of the key figures in the event, the draft resistance movement at Heart Mountain , featuring interviews with resisters Frank Emi and Mits Koshihaya and journalist James Omura , and the "segregation center" that Tule Lake became. After noting the impact of the incarceration, including the erasing of memories of the experience by many and the continuing divides in the Japanese American community to the present, the film ends by circling back to the Omori family's fate at the end of the war.

The title of the film comes from the Japanese traditional belief a rabbit can be seen in a full moon, which is juxtaposed with the American belief in a "man on the moon." In discussing the loyalty questionnaire, Emiko states, "What the government asked of us was to stop seeing the rabbit. Well it's not possible for me to do that. Yet, this questionnaire demanded that we declare our loyalty to the man or the rabbit in the moon." [1]

Film Background

According to Chizu Omori, the film's roots stem from the Redress Movement . After years of living largely outside the Japanese American community, Chizu became active in redress and was also one of the plaintiffs in the class action lawsuit sponsored by the National Council for Japanese American Redress . She became active in the Seattle chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) and was tasked by the group in 1988 to do research on the "loyalty questionnaire" and "no-nos" like her family. Aided by her friend Aiko Yoshinaga-Herzig , who sent her stacks of relevant documents, she found her eyes opened. "Suddenly, in poring over these papers," she wrote, "I had a moment of awakening, something like a revelation. The arcing of events that had put us in the camps and kept us there for all those years began to fall into place." [2]

Emiko's journey began when she discovered serious film as a student at UC Berkeley in the 1960s. After graduating from San Francisco State College in 1967, she was hired as an editor and cinematographer for the KQED television show Newsroom , covering everything from the Black Panthers hippies, and People's Park. She eventually became a freelance cinematographer and filmmaker. At about the same time as Chizu's discovery of the complexities of the loyalty issue, Emiko was working on Hot Summer Winds, an adaptation of two Hisaye Yamamoto stories set prior the war and was struck that everyone she talked to about it assumed it was a movie about the concentration camps. [3]

Over the next eight years, the Omoris worked on Rabbit . The original vision of the film was to focus on Tule Lake (with the working title A Question of Loyalty ) and not to make their own story central. But when Emiko talked Chizu into an on-camera interview to fill in some of the gaps in the storyline, something clicked. "[W]e saw that we needed to create a human story by making it personal," wrote Chizu, and their family story took center stage. In part because of their family's "no-no" status and in part because of their perceived homogeneity of existing camp documentaries, the Omoris found themselves focusing more on stories of resistance. "We were concerned also to try to get more of the female, the women's story out," added Emiko. "A lot of the story had been told by men—and like resistance and all that, that's the male story, kind of the political story—and behind the scenes, you've always got the women, caring for the children, for the elderly, trying to hold the family together." [4]

The film premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January 1999, where it won an award for Best Documentary Cinematography. It was broadcast nationally on PBS in July 1999 and also had national television screenings in Japan, France, and Germany. The Washington Civil Liberties Public Education Program funded the distribution of 570 copies of Rabbit to high schools in Washington state. [5]

Reaction

Rabbit elicited strong reactions from many viewers. "With Japanese Americans, responses ranged from denunciation to grateful thanks, a veritable stew of strong feedback," wrote Chizu. As historian Cherstin Lyon wrote, the "film portrayed the resisters as the heroes and the JACL as the 'jackals' and presented the decisions some made to renounce their citizenship as a fairly rational outcome of their wartime mistreatment that in no way infringed on their ability to call themselves good Americans. The film and the increased attention given to the draft resisters made tensions flair within some circles of Japanese Americans." Karl Nobuyuki, a former national director of the JACL called it "gross distortion of the facts" and criticized it for not including a JACL response. In her otherwise positive review in the Journal of American History , Naoko Shibusawa writes that the filmmakers "exaggerate JACL's influence on the federal government and its coercive power over the Japanese Americans" and "oversimplifies the specific context under which they operated." [6]

Other published reviews and commentary were generally positive. Legal scholar Taunya Lovell Banks highlighted the feminist underpinning of the film, citing "a decidedly female tone." She adds that "Omori's decidedly feminist reading of the Japanese-American World War II experience helps explain why historians might intentionally, or unintentionally, erase the internment from accounts of American twentieth century history." Historian Karen Inouye praises Rabbit as a tool for teaching, calling it : "... a teaching tool that genuinely enhances our students' experience of history by enlivening it at the same time as it demands and rewards intelligent consideration." Naoko Shibusawa writes that "it provides a fascinating interplay of memory, desire, and history," while Franklin Odo calls it "a beautifully filmed documentary." Among its awards are a National Emmy for Outstanding Historical Programming in 1999 and awards from the American Historical Association and the American Anthropological Association. [7]

Might also like Conscience and the Constitution (2001); [ https://resourceguide.densho.org/Resistance%20at%20Tule%20Lake%20(film)/

Resistance at Tule Lake] (2016); From a Silk Cocoon (2005)

For More Information

Official website: http://www.rabbitinthemoonmovie.com .

Rabbit in the Moon trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8vESS2T3vEI .

Kanopy Streaming link: https://www.kanopystreaming.com/product/rabbit-moon-0

Dreifus, Claudia. " Examining Scars from a Wartime American Trauma. " New York Times , July 4, 1999.

Inouye, Karen M. "Viewing World War II Internment through Emiko Omori's Rabbit in the Moon." Journal of American Ethnic History 30.4 (Summer 2011): 31–37.

Michaelson, Judith. " Emotions at War in WWII Tale of Internment. " Los Angeles Times , July 6, 1999.

Omori, Chizu. "The Life and Times of Rabbit in the Moon ." In Last Witnesses: Reflections on the Wartime Internment of Japanese Americans . Edited by Erica Harth. New York: Palgrave, 2001. pp. 215–28.

Reviews

Odo, Franklin. The Public Historian 22.2 (Spring 2000): 123–24.

Shibusawa, Naoko. The Journal of American History 88.3 (Dec. 2001): 1209–11.

Thomas, Kevin. " 'Moon': An In-Depth Look at War Internment. " Los Angeles Times , Feb. 26, 1999.

Footnotes

- ↑ Cited from Karen M. Inouye, "Viewing World War II Internment through Emiko Omori's Rabbit in the Moon," Journal of American Ethnic History 30.4 (Summer 2011), 31.

- ↑ Chizu Omori, "The Life and Times of Rabbit in the Moon ," In Last Witnesses: Reflections on the Wartime Internment of Japanese Americans , edited by Erica Harth (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 218–20, quote from page 219; "Not Your Typical Nisei: JA Women and Adventures in Identity," panel discussion at the Japanese American Museum of San Jose, March 14, 2015, accessed on August 11, 2016 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bu6V4g9q6K8 .

- ↑ Roger Garcia, "Tattoos, Rabbits and Cinematography: Interview with Emiko Omori," In Out of the Shadows: Asians in American Cinema , ed. Roger Garcia (Milano, Italy, Fres srl – Edizioni Olivares, 2001), 173; "Not Your Typical Nisei."

- ↑ C. Omori, "The Life and Times," 225–26, quote from 226; Director's commentary soundtrack from Rabbit in the Moon DVD.

- ↑ C. Omori, "The Life and Times," 216; Alexandra L. Wood, "After Apology: Public Education as Redress for Japanese American and Japanese Canadian Confinement," (Ph.D. dissertation, New York University, 2013), 263–64.

- ↑ C. Omori, "The Life and Times," 216; Cherstin Lyon, Prisons and Patriots: Japanese American Wartime Citizenship, Civil Disobedience, and Historical Memory (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011), 189; Alice Yang Murray, Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008), 432; Naoko Shibusawa, The Journal of American History 88.3 (Dec. 2001), 1210.

- ↑ Taunya Lovell Banks, "Outsider Citizens: Film Narratives About the Internment of Japanese Americans," Suffolk University Law Review 42 (2009), 792, 772; Karen M. Inouye, "Viewing World War II Internment through Emiko Omori's Rabbit in the Moon," Journal of American Ethnic History 30.4 (Summer 2011), 36; Shibusawa, 1211; Franklin Odo, The Public Historian 22.2 (Spring 2000), 123.

Last updated Feb. 1, 2024, 9:46 p.m..

Media

Media