Terminal Island, California

The location of a Japanese fishing village in the Port of Los Angeles whose residents were the first to be evicted from their homes less than a week after the signing of Executive Order 9066 .

The Island's Origin

Terminal Island is an engineered union of two smaller islands—Rattlesnake and Deadman's—constructed for the development of the Port of Los Angeles. Rattlesnake Island in fact was no more than a sand bar extending off the mainland into the bay and so called because of the abundance of rattlesnakes encountered by early explorers. In contrast, Deadman's Island was designated on the maps of Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo in 1542 and later Sebastian Vizcaino in 1602. [1] Its name is a reference to the burials of lost mariners and Indians found by later visitors including Richard Henry Dana who described this "small, dreary-looking island" and the Englishman who was buried here "alone and friendless" in the classic account of his 1834–1836 voyage, Two Years Before the Mast . [2]

In the 1800's as Los Angeles grew in size and potential value as a port city, politicians and industrialists recognized the need for a functional harbor that could accommodate large vessels. Around mid-century, transformation of the beachfront into the international port of today involved three important steps: dredging the slough between Deadman's Island and the mainland; bridging Rattlesnake and Deadman's with a breakwater; and constructing a short but vital rail connection to Los Angeles, the Terminal Railway Line. [3] The newly formed land became known as "Terminal Island," the original islands gone except for a trace of Deadman's marked as Reservation Point.

East San Pedro

The first Japanese to settle in the San Pedro Bay area were abalone and lobster fishermen in 1899. Working from White Point, the venture was lucrative but short-lived, and by 1910 the heart of the community shifted to East San Pedro on the western end of Terminal Island where they turned to sardines and tuna for their catch. [4] Other immigrant groups such as Sicilians, Slovenians, Portuguese, Mexicans, and Filipinos, resided on the opposite end of the island, but the Japanese settlers outnumbered all, reaching at its peak about three thousand in the 1930s.

East San Pedro was essentially a Japanese village on American soil. Insulated and homogeneous, the residents maintained their indigenous identity with significant success, eating Japanese foods, celebrating traditional holidays, and speaking Japanese with greater ease than English. Every resident was connected with the fishing industry in one way or another, most working for canneries like the Van Camp Seafood Company and the White Star Canning Company. In fact the canneries were more than employers. Although Issei men operated the boats, the companies claimed majority share of ownership. [5] They also provided housing for the men and their families, ramshackle bungalows arranged row after row near the factories and waterfront.

The market for canned fish was profitable especially during World War I as the military got priority for meat while consumers at home looked for affordable alternative protein sources. A. P. Halfhill in the early part of the 20th century discovered that steaming albacore tuna produced pale flesh similar in appearance to the white meat of fowl and coined the phrase "chicken of the sea." [6] Some fishermen captured fish with purse seines, large nets that engulfed schools at a time but in the process damaged the flesh and entrapped more than the target prey, which had to be discarded. A more selective method was to fish tuna individually with pole, line, and live-bait. Seemingly onerous, twenty tons of fish could be hauled in an hour by experienced hands. Many Southern California fishermen adopted this imported technique from Japan. [7]

What appeared at the beginning like abundance with no limits, by the late 1930s tuna populations off the California coast dwindled to the point that boats were forced to venture far from home for weeks at a stretch to make their quotas. The high-seas tuna clippers were powerful enough to sail as far as South America and return loaded with tonnage for U.S. markets. [8] In fact, accessibility of such vessels to the Issei was a key factor that led to the uniquely callous treatment of Terminal Islanders immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Exclusion

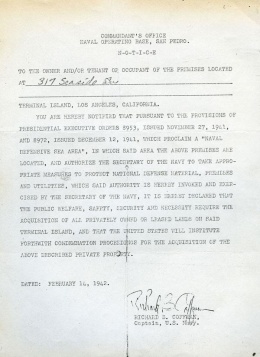

After December 7, 1941, action against the Japanese Terminal Islanders was swift. The FBI initiated widespread arrest of Issei leaders and fishermen, and navy soldiers searched their homes for contraband like radios, cameras, pictures of Japan, even kitchen knives. [9] These Issei after all were in Category A—"known dangerous"—of the FBI's Custodial Detention Index commonly called the ABC Lists . [10] Fishermen had the potential to contact enemy vessels with their long-distance sea-faring boats and shortwave radios according to the Justice Department and the Office of Naval Intelligence . [11] The U.S. government presumed the Issei, who were aliens ineligible for citizenship by law, would be more closely aligned to their mother country than the nation of their residence. Terminal Islanders had the added handicap of being isolated and solidly Japanese while residing adjacent to a U.S. Navy shipyard where warships were under construction. [12]

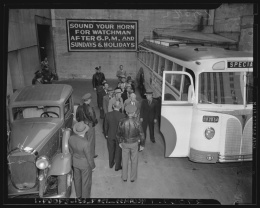

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 that led to the mass removal of all peoples of Japanese ancestry away from the West Coast. While transfer into prison camps began in late March and April, Terminal Islanders were not to have the luxury of weeks to prepare. Even before the presidential order, talk of confusing on-again off-again official pronouncements of eviction kept residents wondering about their immediate future. On February 25th they had their answer: navy personnel started posting notices mandating all Japanese Americans, both aliens and native-born U.S. citizens, off the island within 48 hours. [13]

With the camps still under construction, residents had to move to temporary quarters somewhere off the island in the interim. Women managed the difficult task of finding accommodations and relocating their families without their husbands, Issei men who were now in government custody. [14] In their rush to leave their homes, most suffered massive losses of personal and business property as they unloaded valuable possessions at bargain rates or even at no cost. [15]

After weeks in limbo, Terminal Islanders were given the opportunity to move to Manzanar on April 1st, the first camp ready to take the exiled residents. The eviction transformed the island instantaneously from vibrant community to ghost town. The navy soon occupied East San Pedro, razing homes and shops, and confiscating abandoned boats for military purposes.

Postwar

The Terminal Island detainees left the camps after the war and attempted like others to pick up where they left off. But the disruption of their lives did not end with the war, for fishing, the only occupation that many knew, was out of the question for any Issei resident. Before the war, the California Fish and Game Commission issued commercial licenses annually for a nominal fee but the law changed in 1943 prohibiting licenses for "Japanese aliens." Concerned that such explicit terminology would only invite legal scrutiny, the legislature altered the text in 1945 to "aliens ineligible for citizenship." [16]

Despite, the cosmetic change in the statute's phrasing, the intent clearly was to prevent Japanese specifically, identified solely by their ethnic affiliation, from pursuing a legitimate livelihood. In 1945, Torao Takahashi, a Terminal Island tuna fisherman, challenged the constitutionality of the statute in the Los Angeles County Superior Court by suing the Fish and Game Commission. [17] (See Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission .) Upheld in the lower court in 1946, the Commission appealed to the California Supreme Court, which overturned the decision in its favor, and the case went to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1948. [18] Represented by attorneys Saburo Kido and John Maeno of the Japanese American Citizens League , A.L. Wirin of the American Civil Liberties Union , and Dean Acheson, later the Secretary of State under the Truman administration, the Supreme Court ruled in Takahashi's favor in a 7 to 2 decision. He returned to tuna fishing for a few years after the decision before his death in 1953.

The village is gone and Terminal Island today is largely occupied by the shipping industry. But the legacy carries on with the Terminal Islanders Club, an association of former residents and their descendants. A memorial overlooking the harbor reminds people of the lively neighborhood that once thrived. [19]

For More Information

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians . Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1982. Foreword by Tetsuden Kashima. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997. Available at https://www.archives.gov/research/japanese-americans/justice-denied [See Chapter 3 for a description of the eviction of Terminal Islanders https://www.archives.gov/files/research/japanese-americans/justice-denied/chapter-3.pdf ]

Japanese American National Museum. Terminal Island Life History Project. 2001. http://content.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt367n993t .

Moffat, Susan. "Terminal Islanders Club: A Paradise Lost, Never Forgotten." Los Angeles Times , Jan. 5, 1994. http://articles.latimes.com/1994-01-05/news/mn-8622_1_terminal-island .

Preserving California's Japantowns - Terminal Island. 2012. http://www.californiajapantowns.org/terminalisland.html .

Takahashi Hoffecker, Lilian. "A Village Disappeared." American Heritage 52.8 (Dec. 2001): 64–71. http://www.americanheritage.com/content/village-disappeared .

Footnotes

- ↑ J.M. Guinn, "The Lost Islands of San Pedro Bay," Annual Publication of the Historical Society of Southern California 10 (1915): 95–100; Anna Marie Hager, "A Salute to the Port of Los Angeles: From Mud Flats to Modern Day Miracle," California Historical Society Quarterly 49 (1970): 329–35.

- ↑ Richard Henry Dana, Two Years before the Mast: A Personal Narrative of Life at Sea (New York: F. M. Lupton).

- ↑ Guinn, "The Lost Islands"; Franklyn Hoyt, "The Los Angeles & San Pedro: First Railroad South of the Tehachapis," California Historical Society Quarterly 32 (1953): 327–48; Hager, "A Salute to the Port of Los Angeles."

- ↑ Eiji Tanabe, "Japanese Fishermen Have Made Important Contribution to Progress of Industry," Pacific Citizen , March 27, 1948, 1.

- ↑ Leonard Broom and Ruth Riemer, Removal and Return: The Socio-Economic Effects of the War on Japanese Americans (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1949).

- ↑ Arthur F. McEvoy, The Fisherman's Problem : Ecology and Law in the California Fisheries, 1850-1980 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

- ↑ Don Estes, "Kondo Masaharu and the Best of All Fishermen," Journal of San Diego History 23 (1977): 1-19; Lilian Takahashi Hoffecker, "A Village Disappeared," American Heritage 52.8 (Dec. 2001), 64–71

- ↑ Takahashi Hoffecker, "A Village Disappeared"; McEvoy, The Fisherman's Problem ; Estes, "Kondo Masaharu."

- ↑ PM Nagano, "Leading to Executive Order 9066," American Baptist Quarterly 17 (1998): 105-112.

- ↑ Bob Kumamoto, "The Search for Spies: American Counterintelligence and the Japanese American Community 1931-1942," Amerasia Journal 6.2 (1979): 45-75; Louis Fiset, Nikkei in the Pacific Northwest: Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians in the Twentieth Century (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005).

- ↑ Kumamoto, "The Search for Spies"; Curt Gentry, J. Edgar Hoover : The Man and the Secrets (New York: Norton, 1991).

- ↑ Kumamoto, "The Search for Spies."

- ↑ Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1982).

- ↑ Dorothy Swaine Thomas and Richard S. Nishimoto, The Spoilage (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1946).

- ↑ Broom and Riemer, Removal and Return .

- ↑ Frank F. Chuman, The Bamboo People: The Law and Japanese-Americans (Del Mar, Calif.: Publisher's Inc., 1976); Torao Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission et al. , U.S. Supreme Court, 1948, accessed on April 2, 2012 at http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?navby=case&court=us&vol=334&invol=410 .

- ↑ Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission , Superior Court of Los Angeles County, 1946.

- ↑ Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission , California Supreme Court, 1947; Torao Takahashi v. Fish and Game Commission et al. , U.S. Supreme Court, 1948.

- ↑ Susan Moffat, "Terminal Islanders Club: A Paradise Lost, Never Forgotten'" Los Angeles Times , Jan. 5, 1994, accessed at http://articles.latimes.com/1994-01-05/news/mn-8622_1_terminal-island .

Last updated Dec. 21, 2023, 3:46 a.m..

Media

Media