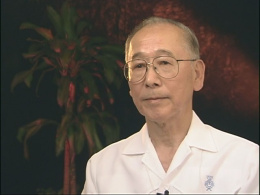

William Marutani

| Name | William Marutani |

|---|---|

| Born | March 21 1923 |

| Died | November 15 2004 |

| Birth Location | Kent, Washington |

| Generational Identifier |

Lawyer, judge and member of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC). A longtime advocate for civil rights and the first Japanese American to gain a judicial appointment outside the West Coast and Hawai'i, William Marutani (1923–2004) was also the only Japanese American CWRIC commissioner.

Marutani was born and raised in Washington state, calling Kent his hometown. While attending the University of Washington, he was forcibly removed with his family and incarcerated first at Pinedale Assembly Center , then at Tule Lake . He was among the first to leave the concentration camps in the fall of 1942, departing to attend Dakota Wesleyan University in Mitchell, South Dakota, with the assistance of the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council . [1] He was drafted two years later, eventually serving in the Military Intelligence Service in the postwar occupation of Japan. In Japan, he met his wife, Victoria, who was working as a civilian nurse. He also had a sister who had been raised in Japan and had been in Hiroshima when the bomb fell. Though she survived, her husband was killed and her two children injured in the blast. [2]

Upon his discharge, Marutani finished his undergraduate degree and went on to law school at the University of Chicago, graduating in 1953. He joined the Philadelphia firm of MacCoy, Evans and Lewis, remaining with them for twenty-three years and eventually becoming a senior partner. He and Victoria raised eight children. He joined the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), becoming president of its Philadelphia chapter in 1955 and also served as the JACL's national legal counsel from 1962 to 1970. In that capacity, he was one of the organization's most ardent supporters of the Civil Rights Movement. After the signing of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, he went to Bogalusa, Louisiana, as a volunteer lawyer to help enforce the new law, where the temporary law office he worked out of was bombed. As JACL counsel, he also was allowed to present arguments on behalf of Japanese Americans before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1967 during the landmark Loving v. Virginia case that struck down anti-miscengenation laws. He also argued for establishing defense funds for Asian American student activists and Black Panthers. In 1975, Pennsylvania Governor Milton Shapp appointed Marutani to be a judge of the Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia. Upon his appointment, he told a reporter, "It seems that the Bs have played an important role in my life: barbed wire, bombs, bar, and now the bench." Two years later, he won reelection to a ten year term. [3]

Marutani had been an advocate of reparations from early on, once urging Clifford Uyeda , who was heading the JACL's redress campaign, to raise the desired amount of reparations from $10,000 to $25,000. With the formation of the CWRIC, Marutani was among the commissioners appointed by President Jimmy Carter and was the only Japanese American member of the commission. At the hearings, he jousted with unrepentant exclusion architect John J. McCloy , the assistant secretary of war in 1942, reading back to McCloy a transcript from a phone conversation in which has was reported to have said "... if it is a question of the safety of the country and the Constitution, why the Constitution is just a scrap of paper to me," which McCloy denied saying. He also challenged McCloy when he claimed that Japanese Americans had not been "adversely affected" by their expulsion and imprisonment, the two men getting into a shouting match. Marutani was deeply moved by the testimony of Japanese Americans, telling Alice Yang Murray, "For me it's a mixture of anger and grief, of rage and frustration, choking back a lump in my throat, fighting back tears constantly." [4] He was among the commissioners who recommended reparations of $20,000 and governmental apology, leading to the eventual passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 . In making the recommendation, Marutani recused himself from receiving any reparations payment for himself.

After an unsuccessful electoral bid for the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in 1983, Marutani retired as a judge in 1986. He remained active in the Japanese American community, writing a column for the Pacific Citizen newspaper and serving as board chairman of the National Japanese American Memorial Foundation. He passed away at his home on November 15, 2004.

For More Information

Daniels, Roger. The Japanese American Cases: The Rule of Law in Time of War . Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2013.

Finding aid for the William M. Marutani Papers , Japanese American National Museum

Irons, Peter. Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases . New York: Oxford University Press, 1983. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Marutani, William. Densho oral history. Interviewed by Becky Fukuda and Gary Kawaguchi, September 11, 1997, Los Angeles.

———. Redress Oral History Project (1998-1999) . Interviewed by Mitchell Maki, Media, Pennsylvania, August 27, 1998. Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum.

Murray, Alice Yang. Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress . Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008.

Robinson, Greg. After Camp: Portraits in Midcentury Japanese American Life and Politics . Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

Sims, Gayle Roman, " Judge William M. Marutani, 81 ." Philadelphia Inquirer , Nov. 20, 2004.

Footnotes

- ↑ There is a photo of Marutani and other Nisei students at Dakota Wesleyan in Gary Okihiro's Storied Lives: Japanese American Students and World War II (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999).

- ↑ William Marutani, Densho oral history, interviewed by Becky Fukuda and Gary Kawaguchi, September 11, 1997, Los Angeles.

- ↑ Hawaii Herald , April 15, 1983, p. 14; Gayle Roman Sims, "Judge William M. Marutani, 81," Philadelphia Inquirer , November 20, 2004, accessed on June 11, 2013 at http://articles.philly.com/2004-11-20/news/25380217_1_law-degree-civil-rights-philadelphia-bar-association ; Pacific Citizen , December 23, 1955, p. B-11, accessed on Jan. 12, 2018 at http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-pc-27-51/ ; Greg Robinson, After Camp: Portraits in Midcentury Japanese American Life and Politics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), p. 239–40; Katie L. Furuyama, "Imagining Equality, Constructing Ethnicity, Race, Identity, and Nation: The Japanese American Citizens League and the League of United Latin American Citizens" (Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Irvine, 2012), p. 80; Maurice Lewis, Jr., "The B's in Bill's Bravura," Pacific Citizen , May 2, 1975, p.2, reprinted from the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin ; quote from the last.

- ↑ Peter Irons, Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), p. 353; Alice Yang Murray, Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008), p. 16 and 349, with quote from the latter.

Last updated July 15, 2020, 3:33 p.m..

Media

Media