Ben Kuroki

| Name | Ben Kuroki |

|---|---|

| Born | May 16 1917 |

| Died | September 1 2015 |

| Birth Location | Gothenburg, Nebraska |

| Generational Identifier |

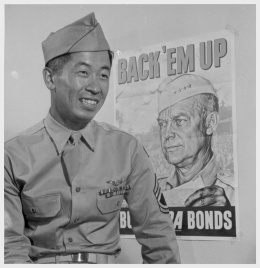

War hero and journalist. Nisei and Nebraska native Ben Kuroki was able to break through prejudice in the U.S. military to become a decorated aerial gunner who flew 58 combat missions over both Europe and the Pacific. His exploits were highly publicized, and he was even dispatched to the concentration camps holding West Coast Japanese Americans to encourage the inmates to serve in the army. After the war, he became a journalist for several publications, retiring in 1984. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal in 2005.

Early Life and WWII Service

Ben Kuroki was born in Gothenburg, Nebraska, on May 16, 1918, as one of ten children of Issei parents Shosuke and Naka Kuroki. Shosuke had migrated from Kagoshima prefecture and worked various jobs in the continental U.S. before work on a Union Pacific Railroad section crew brought him to Nebraska, where he eventually decided to settle and farm in the North Platte River Valley. Naka, who was from the Yokohama/Nara area, eventually joined him as a picture bride , and five boys and five girls ensued, with Ben being the third of the sons. When Ben was around six, the family moved to Hershey, a town with a population of less than 500 located about thirteen miles west of North Platte, where Ben grew up. [1]

The Kurokis grew vegetables that they sold directly to stores in North Platte and also to people who came to the farm. In later interviews, Ben remembered his childhood as having been "terribly poor" and having had to "go out and work in the fields all day long" from age five. He attended schools in Hershey and became best friends with Gordy Jorgenson, with whom he learned to hunt from a young age. He attended Hershey High School, where he played baseball and basketball and was the class vice-president (Gordy was the president), and graduated in 1936 as part of a class of ten. The Kurokis were one of a handful of Japanese families in the valley, and Ben remembered the parents hiring someone to try to teach Japanese to the kids. He also remembered feeling embarrassed when his parents would speak Japanese when encountering other Issei in public places. After graduation, Ben continued to help with the farm, while also using a family truck to haul produce as far away as Arkansas and California. He also took flying lessons in a Piper Cub and made his first solo flight in 1941. [2]

On the morning of December 7, 1941, Kuroki was among a group of Nisei attending a organizational meeting of the Japanese American Citizens League led by JACL Executive Secretary Mike Masaoka , who was trying to organize a North Platte chapter. In the midst of the meeting, FBI agents arrested Masaoka, at which point Kuroki and the others learned about the attack on Pearl Harbor. The next day, Ben and his brother Fred—with the approval of their father—enlisted for the army and took their physicals, joining tens of thousands of other young men across the country. But after not hearing anything for two weeks, while friends such as Gordy were accepted, Ben saw what was going on. Hearing on the radio that the army air corps was taking enlistments at Grand Island, about one hundred and fifty miles away, Ben and Fred drove there and managed to sign up for the United States Army Air Forces. While Ben was allowed in, Fred was eventually kicked out and transferred to what Ben called a "ditch digging unit." [3]

After basic training, Kuroki was sent to the Air Corps Clerical School in Fort Logan, Colorado, then to Barksdale Field in Louisiana and Fort Myers, Florida, where he was assigned to the 409th Bomb Squadron of the 93rd Bombardment Group. Despite his prior flight training and being a good shot due his hunting experience, he was not allowed on the planes and was assigned to do clerical work. Higher ups also tried to transfer him out on a couple of occasions, but Kuroki recalled tearfully begging to be allowed to stay in. Racism and being the only Japanese American also took its toll, as he avoided going into town with his buddies fearing racial harassment by locals. "There were nights that I stuck my head in the pillow, and I cried," he recalled in an oral history. "I was so damn lonesome." He nonetheless stuck it out, and traveled with the unit to England in November 1942, which would be their initial base. The first B-24 unit to arrive in England, the 93rd was famously greeted by King George. He initially served as a clerk typist, but also learned how to quickly assemble and disassemble guns. [4]

The 93rd flew B-24 bombers over Europe and North Africa. Its crew consisted of around nine men including a pilot, navigator, engineer, radio operator, and bombardier, along with gunners on the front, sides, and tail of the plane, and one on top in the turret. The main job of the gunners was to shoot at enemy planes that were trying to to shoot them down so as to allow their plane to complete its bombing missions. It was nerve wracking duty performed under arduous conditions, as B-24s were neither heated nor pressurized, resulting in freezing temperatures in flight and the need for heavy electric warming suits. Given the high casualty rate, crew members were assigned a tour of duty of twenty-five missions, after which they could serve out their terms as an instructor or in other ground duty. A typical bomber crew would be expected to survive around fifteen missions and would have only about a one-in-three chance of surviving a full tour of duty. [5]

As the crews began their bombing missions, more gunners were needed, as some of the men froze up once in battle. Given this shortage, Ben was finally accepted as a gunner and sent to a gunnery school in English for just a couple of weeks, before being assigned to a crew in December, his prior hunting experience making him an expert marksman. His first mission took place on December 13, 1942. In his early missions, he served as one of two waist gunners, before moving to tail after a prior tail gunner was wounded, then to the turret. Ben's crew moved to Algeria and bombed German targets in North Africa, then began missions in Italy. By February 1943, they had flown fourteen missions. On their way back to North Africa, they got lost and made an emergency landing in Spanish Morocco and ended up being held in Spain for three months while their fate was sorted out. Upon their return, Ben and his crew were sent to the vicinity of Benghazi, Libya, to practice low level flying for a secret mission to destroy a heavily defended German fuel facility in Ploesti, Romania, 1,200 miles away. The August 1, 1943 raid dubbed "Operation Tidal Wave" saw 177 bombers go out, out of which 53 were lost, along with 310 men killed, about one in five. Ben's crew made it back intact. Having completed his twenty-five missions, Ben nonetheless volunteered for five more. On his 30th mission, his turret was shattered by flack, and he was knocked unconscious, but he woke up otherwise uninjured. [6]

Celebrity Speaker

By the time Kuroki returned to the U.S. in December 1943, his exploits had become well-known, as articles on him appeared in the Stars and Stripes , American Army , and other publications. By July 1943, the Pacific Citizen was referring to him as "Nisei America's No. 1 hero in the European theater of operations," and reported in November on his receiving a Distinguished Flying Cross for his role in the Ploesti raids. But his fame would rise exponentially during his stint in the U.S. in the first half of 1944. [7]

Landing initially in New York, Kuroki briefly visited Hershey then Denver, en route to California, where he was assigned for a three-month rest and rehabilitation stint at the Santa Monica Army Air Forces Redistribution Center No. 3 in what had been the Edgewater Beach Club, one of several segregated private beach clubs in Santa Monica that had been built in the 1920s. At a time when Japanese Americans were excluded from the West Coast, Kuroki would have been one of the few Japanese Americans in California living in something other than a concentration camp. [8]

While in California, Kuroki was booked as a guest on singer Ginny Simms' popular radio show for January 25, 1944, but at the last minute, NBC canceled his appearance, with a network spokesperson citing the "whole American-Japanese question" as "highly controversial." On February 4, Kuroki gave a speech at the Commonwealth Club, a prestigious public affairs organization based in San Francisco, that detailed his life story, military exploits, and the wartime dilemma of Japanese Americans. The speech—which was ghostwritten by Staff Sergeant Bob Evans—was greeted by a long standing ovation and extensive positive media coverage, including a profile in TIME Magazine. He made a triumphant return to the Simms show on February 22, this time actually appearing on air. After his three-month stint in Santa Monica, he moved on the Pueblo, Colorado, where he served as an aerial instructor. [9]

With the army beginning to draft Nisei from the concentration camps, the War Department and the War Relocation Authority approached Kuroki about visiting some of the camps to lift morale and build support for serving in the armed forces. A reluctant Kuroki agreed, and he ended up visiting three of the camps, Heart Mountain (April 24 to 30), Minidoka (May 2 to 7), and Topaz (May 19 to 23). The visits were broadly similar, as camp administrators and inmate leaders scheduled a succession of speeches, meetings, visits with various inmate groups, and socializing for Kuroki. Despite adulatory coverage of his visit in the camp newspapers, inmate reception was decidedly mixed, with younger Nisei and Sansei mostly approving, while many Issei were indifferent or disapproving. Heart Mountain Community Analyst Asael T. Hansen reported that "most of the community responded favorably to him," and that he "had the greatest influence on children and young people, which is as it should be," while also noting Issei objections to "his whole-hearted identification with America in the war with Japan and his emphatic prediction that 'we' would soon bomb Japan, and that Japan would be defeated." Similarly, Topaz observer James Sakoda reported that he referred to "our dishonorable ancestors," causing Issei to call him "names as inu and Chosenjin." Kuroki also clashed with draft resisters at Heart Mountain, later calling them "fascists" and "no good to any country." In an oral history fifty years later, Kuroki took on a different tone, telling interviewer Arthur A. Hansen, "... in a way, I couldn’t blame some of them for feeling like they did.... I don’t know how I would have reacted in the same situation." Perhaps learning from Kuroki's mixed reception, the WRA later brought an another decorated Nisei veteran to speak in various camps. Thomas Taro Higa , a Kibei from Hawai`i, spoke to Issei audiences in Japanese, avoided nationalistic language, and appealed to them as parents. According to Sakoda, "Many of the parents were crying as they heard him speak." [10]

The Pacific War and Postwar Activism

Soon after his WRA camp visits, Kuroki decided to sign up for more missions in the Pacific, inspired in part by a racist incident in Denver and by the death of Gordy while serving in the Pacific. To his initial surprise, he was quickly accepted as a part of the 505th Bomb Group training in Harvard, Nebraska. But after three months of training, he receives word from Washington, D.C. that persons of Japanese descent would not be allowed to fly combat missions in the Pacific. A vigorous letter writing campaign led by University of California Vice-President Monroe Deutsch eventually leads to the War Department changing its mind, and Kuroki is allowed to go. In his honor, the crew nicknames their plane the "Honorable Sad Saki." After dodging another attempt to stop him, he cross the Pacific and land on Tinian in the Mariana Islands. Having been recently captured by the Allies, there were still Japanese stragglers in caves, and Kuroki had to be protected from trigger happy Allied soldiers. He told Hansen that "felt a hell of a lot safer when I was on a bombing mission inside that B-29" than when he was on the ground. [11]

Conditions overall were much better for Kuroki than in Europe. His crew flew the much larger B-29 bombers that were pressurized, eliminating the extreme temperatures. Kuroki also called the enemy "mild" compared to the Germans. A tail gunner throughout his Pacific missions, he recalled low altitude fire bombings of Tokyo in which he saw "the whole city... up in a blaze." Kuroki's war ended on the ground, when he was slashed with a knife by a ground crew member on Tinian after a dispute, landing him in the hospital. The atomic bombs fell while he was hospitalized. [12]

Back in the U.S. by October 1945, Kuroki embarked on a seemingly non-stop series of speeches, serving as "the unofficial spokesman of the Nisei" according to Pacific Citizen columnist John Kitasako, telling the story of the Nisei soldiers and calling for an end to racism and intolerance. In addition to appearing on nationally broadcast events such as the New York Herald Tribute forum on October 29 and "America's Town Meeting of the Air" on ABC on November 22, he spoke at high schools, civic clubs and other smaller events, at one point making twelve speeches in seven days in the New York area in January and February 1946. After his official discharge from the army in February and an appearance at the JACL convention in Denver in March, he agreed to join the JACL's efforts to secure naturalization rights for the Issei and toured the country over the next several months, sometimes accompanied by Mike Masaoka. He also married Shige Tanabe of Pocatello, Idaho, on August 9, whom he had met through the Masaokas while on his speaking tour. That same month, Kuroki began a position as the executive secretary of the Washington, D.C., based East West Association, an organization that had been co-founded by Pearl S. Buck . In that role, he continued his breakneck speaking schedule in the East and Midwest, at one point giving twenty-four talks in seven days. His profile grew even higher with the October 1946 release of Boy from Nebraska , a biography of Kuroki by Ralph Martin. With the pace wearing on him—and with the birth of his and Shige's first child, a girl, in September—he decided to seek a more settled existence, quitting East West in March 1947 to join his wife and child in Pocatello. [13]

Later Life

Kuroki enrolled at the University of Nebraska in the fall of 1947 majoring in journalism, and upon his graduation, spent most of his subsequent professional life as a journalist—likely the first Japanese American to be an editor of a mainstream newspaper—owning and operating two small newspapers in Nebraska, before purchasing the Williamston [Michigan] Enterprise in 1955. After about a decade in Michigan, he moved to California to be closer to a daughter who was going to the University of California at Santa Barbara and took a position at the Ventura County Star-Free Press , where he remained until his retirement in 1984. [14]

After his period of fame during and immediately after World War II, Kuroki largely kept a low profile. One of the relatively few Nisei Republicans, he supported Barry Goldwater for president in 1964 and implicitly supported California's Proposition 14, which would have amended the state constitution to prevent any fair housing laws. In 1991, he was the keynote speaker at opening the Museum of Nebraska's exhibition on Nebraska during World War II. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal in 2005. He died in Camarillo, California in 2015 at the age of 98. [15]

For More Information

Hansen, Arthur A. "Sergeant Ben Kuroki's Perilous 'Home Mission': Contested Loyalty and Patriotism in the Japanese American Detention Center." In Remembering Heart Mountain: Essays on Japanese American Internment in Wyoming . Ed. and contribution by Mike Mackey. Powell, Wyoming: Western History Publications, 1998. 153-75.

Lukesh, Jean A. Lucky Ears: The True Story of Ben Kuroki , World War II Hero. Grand Island, NE: Field Mouse Productions, 2010. [Young adult biography of Kuroki.] https://archive.org/details/luckyearstruesto00benk/

Martin, Ralph G. Boy from Nebraska . New York: Harper & Row Brothers, 1946.

Most Honorable Son . Documentary produced by KDN Films. Written and Directed by Bill Kubota. 2007. 57 min. PBS website for the documentary, http://www.pbs.org/mosthonorableson/ .

Footnotes

- ↑ "An Oral History with Ben Kuroki," interviewed by Arthur A. Hansen, Oct. 17, 1994, Ojai, California, pp. 1–9, Center for Oral and Public History, California State University, Fullerton, Japanese American Oral History Project, OH 2385, http://digitalcollections.archives.csudh.edu/digital/collection/p16855coll4/id/12092/rec/3 ; Most Honorable Son documentary film produced by KDN Films and directed by Bill Kubota, 2007; "United States Census, 1920", database with images, FamilySearch ( https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MCK2-Y6D : 2 February 2021), Shosuke Kuroki, 1920; "United States Census, 1930," database with images, FamilySearch ( https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:XQ29-LV7 : accessed 14 February 2022), Ben Kujoki in household of Samie Kujoki, Hershey, Lincoln, Nebraska, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) ED 20, sheet 4B, line 92, family 78, NARA microfilm publication T626 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2002), roll 1287; FHL microfilm 2,341,022; "United States Census, 1940," database with images, FamilySearch ( https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K9MD-HRQ : 6 January 2021), Ben Karski in household of Sam Karski, Hershey Election Precinct, Lincoln, Nebraska, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 56-20, sheet 3B, line 72, family 53, Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940, NARA digital publication T627. Records of the Bureau of the Census, 1790 - 2007, RG 29. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2012, roll 2256. Though official records list his year of birth as 1917, Kuroki claimed a 1918 birthdate in the later interviews noted above, the latter date also corresponding to his listed age in the many newspaper accounts of his World War II exploits. Prewar census records for the Kurokis list various and conflicting numbers of children. The number and place in the family are also based on the interviews.

- ↑ "An Oral History with Ben Kuroki," 6–30; Most Honorable Son .

- ↑ "An Oral History with Ben Kuroki," 27–28; Most Honorable Son ; "ditch digging" quote from the latter.

- ↑ "An Oral History with Ben Kuroki," 29–30, 98; Most Honorable Son ; Pacific Citizen , Jan. 1, 1944, 1, 3.

- ↑ "An Oral History with Ben Kuroki," 32–34; Most Honorable Son ; Arthur A. Hansen, "Sergeant Ben Kuroki's Perilous 'Home Mission': Contested Loyalty and Patriotism in the Japanese American Detention Center.," in Remembering Heart Mountain: Essays on Japanese American Internment in Wyoming , ed. Mike Mackey (Powell, Wyoming: Western History Publications, 1998), 170.

- ↑ "An Oral History with Ben Kuroki," 30–37; Ben Kuroki and Shige Kuroki interview by Frank Abe (primary) and Frank Chin (secondary), Segment 1, Camarillo, California, Jan. 31, 1993, Frank Abe Collection, Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-122/ddr-densho-122-21-transcript-ee4667b96e.htm ; Most Honorable Son ; Pacific Citizen , Jan. 1, 1944, 1, 3; Bill Yenne, Rising Sons: The Japanese American GIs Who Fought for the United States in World War II (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2007), 138.

- ↑ Pacific Citizen , Feb. 11, 1943, 5, July 17, 1943, 1, and Nov. 20, 1943, 3; "An Oral History with Ben Kuroki," 63.

- ↑ Ben Kuroki & Shige Kuroki interview, Segment 2; "Historic California Posts, Camps, Stations and Airfields: Santa Monica Army Air Forces Redistribution Center No. 3," militarymuseum.org, http://militarymuseum.org/SantaMonicaAAFRedistCtr.html ; Jean Trinh, "How Beach Clubs Changed Santa Monica During a Segregated Era," LAist, Jan. 20, 2014, https://laist.com/news/entertainment/how-beach-clubs-changed-santa-monica ; "An Oral History with Ben Kuroki," 43–45, both accessed on June 30, 2022.

- ↑ Pacific Citizen , Jan. 29, 1944, 1, 4; "An Oral History with Ben Kuroki," 46–51; Charles M. Wollenberg, "'Dear Earl'" The Fair Play Committee, Earl Warren, and Japanese Internment," California History 89.4 (2012), 45; Hansen, “Sergeant Ben Kuroki’s Perilous ‘Home Mission,'" 158–60; TIME Magazine, Feb. 7, 1944, 76–77; San Francisco Chronicle , Feb. 5, 1944, 2; Oakland Tribune , Feb. 5, 1944.

- ↑ Arthur A. Hansen, "The 1944 Nisei Draft at Heart Mountain, Wyoming: Its Relationship to the Historical Representation of the World War II Japanese American Evacuation," OAH Magazine of History 10.4 (Summer 1996): , 51; "An Oral History with Ben Kuroki," 53–59; Asael T. Hansen, Weekly Report for Apr. 21–27, 1944, Apr. 28, 1944, Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records (JAERR), Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, call number BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder M2.37:1, https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/k65q537g/?brand=oac4 ; Asael T. Hansen, Weekly Report for Apr. 28 to May 4, 1944, May 5, 1944 JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder M2.37:1, https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/k65q537g/?brand=oac4 ; Heart Mountain Sentinel Supplement, Apr. 25, 1944, https://f001.backblazeb2.com/file/densho-public/ddr-densho-97/ddr-densho-97-411-mezzanine-9dc5ec407d.pdf ; Heart Mountain Sentinel , Apr. 29, 1944, 1; Hansen, “Sergeant Ben Kuroki’s Perilous ‘Home Mission,'" 154, 159–60; Letter, James Sakoda to Dorothy Thomas, May 15, 1944, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder W 1.32:3, http://content.cdlib.org/ark:/28722/bk001304v36 ; Dorothy Thomas notes on Sakoda's journal, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder R 20.82 http://content.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/k69886qw , p. 14 ("Kuroki's Visit"); Toshio Mori, "Topaz Welcome Kuroki," JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder H2.02:51, https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/k6377gp5/?brand=oac4 ; Cherstin Lyon, Prisons and Patriots: Japanese American Wartime Citizenship, Civil Disobedience, and Historical Memory (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011), 149–51; Roger Daniels, Concentration Camps, U.S.A.: Japanese Americans and World War II (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971), 128; Dorothy Thomas notes on Sakoda's journal, JAERR BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder R 20.82 http://content.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/k69886qw , p. 8 ("Pfc. Higa's Visit").

- ↑ Ralph G. Martin, Boy from Nebraska (New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1946), 171–76; Ben Kuroki & Shige Kuroki interview, Segment 3; Most Honorable Son ; "An Oral History with Ben Kuroki," 63–65.

- ↑ "An Oral History with Ben Kuroki," 66–68; Most Honorable Son ; Yenne, Rising Sons , 140–41.

- ↑ Pacific Citizen , Nov. 3, 1945, 2, Nov. 24, 1945, 2, Feb. 9, 1946, 5, Mar. 9, 1946, 1, Mar. 30, 1946, 1–2, Apr. 20, 1946, 3, Aug. 10, 1946, 1, Aug. 31, 1946, 5, Sept. 7, 1946, 3, Oct. 12, 1946, 3, Mar. 8, 1947, 8, Sept. 27, 1947, 7; John Kitasako, "Washington News-Letter: Sgt. Ben Kuroki, Nisei GI Hero, Is Home from the Wars," PC, 11/10/45, 3; John Kitasako, "Washington News-Letter: Ben Kuroki's 59th Mission Is Quite an Arduous Affair," PC, 11/2/46, 5; Hansen, "The 1944 Nisei Draft," 52; Ben and Shige Kuroki interview, Segment 5; "An Oral History with Ben Kuroki," 72, 78.

- ↑ Pacific Citizen Oct. 4, 19476, 6; Dec. 2, 1955, 1; Larry Tajiri, "Nisei USA: Ben Kuroki Goes to Press," Pacific Citizen , Apr. 22, 1950, 4; Larry Tajiri, "Nisei USA: The Country Editor," Pacific Citizen , Feb. 2, 1952, 4; Larry Tajiri, "Vagaries: 'Boy from Nebraska' Sequel," Pacific Citizen , June 17, 1955, 1; "An Oral History with Ben Kuroki," 84–91; Christopher Goffard, "Ben Kuroki Dies at 98; Japanese American Overcame Bigotry to Fly Bombing Raids in World War II," Los Angeles Times , Sept. 5, 2015, accessed on June 30, 2022 at https://www.latimes.com/local/obituaries/la-me-0906-ben-kuroki-20150906-story.html .

- ↑ Pacific Citizen , Feb. 17, 1967, 1; Greg Robinson, "An Uneasy Alliance: Blacks and Japanese Americans, 1954–1965," in After Camp: Portraits in Midcentury Japanese American Life and Politics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 238; Hansen, "The 1944 Nisei Draft," 52; Yenne, Rising Sons , 141; Richard Goldstein, "Ben Kuroki Dies at 98; Japanese-American Overcame Bias to Fight for U.S.," New York Times , Sept. 5, 2015, accessed on June 30, 2022 at https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/06/us/ben-kuroki-dies-at-98-fought-bias-to-fight-for-us.html .

Last updated July 19, 2022, 10:33 p.m..

Media

Media