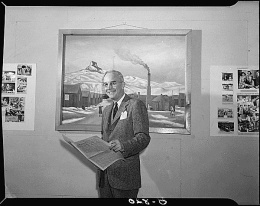

Dillon Myer

| Name | Dillon Seymour Myer |

|---|---|

| Born | September 4 1891 |

| Died | October 25 1982 |

| Birth Location | Hebron, OH |

War Relocation Authority (WRA) director. From 1942 to 1946, Dillon Seymour Myer (1891-1982) oversaw the WRA, the government agency charged with the forced removal and resettlement of Japanese Americans. He inherited "what may well have been the toughest, most exasperating civilian job during the war," as Michi Nishiura Weglyn put it, when the WRA was still in its initial operating stage. [1] His complex relationship with the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), which served as his guide and informer, offered some JACL leaders with negotiating powers, while dividing the detainee population. In his later years, he regretted the mass incarceration, but also stated that it brought some positive results.

Before the War

Dillon Myer was born on September 4, 1891, in Hebron, Ohio, to a middle-class family. He received a bachelor of science degree from Ohio State University with a specialization in agronomy and a master of education degree from Columbia University. He initially taught at the University of Kentucky and then served as an agricultural demonstration agent in Indiana. A product of the Progressive Era's penchant for greater efficiency and government control, one of his early federal positions was with the Agricultural Adjustment Administration in 1933. He continued his administrative career during the New Deal, moving to Washington D.C. to work for the Department of Agriculture. He became the assistant chief of the Soil Conservation Service in 1938.

Wartime Role as WRA Director

On June 17, 1942, Myer replaced Milton S. Eisenhower as director of the WRA. Both had built their careers through the Department of Agriculture, knowing little about the Japanese American population, much less the logistics of running the prison camps. One of Myer's first tasks was to announce a leave policy. Fearful of the long-term ramifications of displacement and detention, Myer adopted a program whereby citizens—with the exception of the Kibei —could leave the WRA centers for employment outside the Western Defense Command . Myer would later compare camp life to Indian reservations, "an institutionalized environment, which in turn produces frustration, demoralization, and a feeling of dependency among the residents." [2] In August, the WRA gained full jurisdiction over the camps, once the Western Defense Command "evacuated" all Japanese Americans from their homes in military areas. Myer began drafting an operations manual to manage everything from mess halls to schools at the "relocation centers."

By January 1943, WRA field offices were established in Chicago and Salt Lake City to facilitate resettlement. At the Senate Military Affairs Subcommittee on War Relocation Centers, Myer offered his rationale: "My underlying idea is that since these people are going to continue to be American citizens, they will have to merge into our economy and be accepted as part of it, otherwise we are always going to have a racial problem." [3] Yet, he also applied the same reasoning to limit Japanese American self-administration and cultural activities, citing camp life as "temporary way stations." [4] His policies for leave clearance included loyalty oaths from Nisei inmates and their widespread dispersal to prevent the concentration of the Nisei in any one location. Once resettled, they were kept under close surveillance.

Eventually, the War Department demanded another loyalty reexamination, administered this time by the Western Defense Command in cooperation with the Provost Marshal General's office . Myer defended the WRA's existing clearance procedure and criticized "the frustrating and demoralizing effect the new processing will have upon the evacuees who already have reason to feel that they have been sorted, sifted, and classified beyond anything citizens of this country should have endured." [5]

In July 1943, Myer testified before the subcommittee of the Committee on Un-American Activities headed by Congressman Martin Dies of Texas. Congressman John M. Costello of California was chairman of the subcommittee whose professed purpose was to investigate un-American propaganda activities in the U.S. In reality, Costello was looking for proof of unauthorized collusion between the WRA and the JACL over camp security and release of prisoners. They also questioned the inmates' large number of negative responses to the loyalty questions and lack of interest in volunteering in the army. Joining the bandwagon were politicians such as California Governor Earl Warren , who was opposed to the return of any Japanese Americans to California before the end of the war under the pretext of avoiding possible "public disturbances" that might impede the "war effort." In a 1944 speech before a California audience, Myer accused the press of "fomenting antagonisms" against persons of Japanese ancestry in a "campaign of hate." He praised the 100th Infantry Battalion's "record of patriotic devotion" and defended his resettlement policies as a way to readjust the Nisei into "normal communities where they can develop as normal men and women." [6]

Recent scholars have also scrutinized Myer's association with the JACL in supervising the camps. Richard Drinnon goes so far as to argue that Myer's decision to involve JACL leader Mike Masaoka in forming WRA policy contributed to the rift between the JACL and other detainees. He describes Myer's relationship with Masaoka as "symbiotic," in their use of the camps as "indoctrination centers for 'Americanism.'" [7] Agitators and troublemakers were sent to separate detention camps at Tule Lake .

Myer later wrote that General John L. DeWitt's raison d'être for mass incarceration was unfounded, with evidence to suggest racial bias. Yet he also justified the WRA's "worthwhile results" in facilitating Nisei assimilation and acceptance. He writes that the wartime relocation of Japanese Americans across the U.S. and into the armed forces "led to an understanding and an acceptance on the part of the great American public" and "the breaking down of the results of the 'Yellow Peril' propaganda." [8]

After the War

Myer served as director of the Federal Housing Authority in the late 1940s as the government pulled the plug on its wartime housing programs. In 1946, his work with the WRA won him the Medal for Merit by President Harry Truman and an honorable citation by the JACL for "courageous and inspired leadership." Calling him "a champion of human rights," the JACL acknowledged his fight against "war hysteria, race prejudice, and misguided hate" and effort in promoting Japanese Americans as "loyal and sincere Americans." [9] Some scholars, however, have criticized Myer's paternalistic approach, citing similarities between the way he managed the WRA and the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the early 1950s. During his tenure as commissioner, patriotic citizenship and assimilation remained the hallmark of the bureau's educational and vocational curriculum, a throwback to his administrative style at the WRA. [10] Towards the end of his life, he opposed the redress movement and use of the term "concentration camp" to describe the incarceration centers. Myer's correspondence and memoranda pertaining to his public life from 1934 to 1966 are housed at the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum in Independence, Missouri. He died on October 25, 1982.

For More Information

Drinnon, Richard. Keeper of Concentration Camps: Dillon S. Myer and American Racism . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

Myer, Dillon S. Uprooted Americans: The Japanese Americans and the War Relocation Authority During World War II . Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1971.

Myer, Dillon S. Papers. Biography. Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. http://www.trumanlibrary.org/hstpaper/myers.htm .

Footnotes

- ↑ Michi Nishiura Weglyn, Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America's Concentration Camps (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999), 119.

- ↑ Dillon S. Myer, Uprooted Americans: The Japanese Americans and the War Relocation Authority During World War II (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1971), 294.

- ↑ Myer, Uprooted Americans , 56.

- ↑ Kenneth R. Philp, "Dillon S. Myer and the Advent of Termination: 1950-1953," The Western Historical Quarterly 19:1 (Jan 1988): 38.

- ↑ Weglyn, Years of Infamy , 223.

- ↑ Bill Hosokawa, Nisei: The Quiet Americans (Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 2002), 386; Brian Masaru Hayashi, Democratizing the Enemy: The Japanese American Internment (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 148-149; Roger Daniels, Asian America: Chinese and Japanese in the United States Since 1850 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988), 292-293; Dillon Myer, "Relocation Problems and Policies" (Tuesday Evening Club, Pasadena, California, March 14, 1944). http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu .

- ↑ Richard Drinnon, Keepers of Concentration Camps: Dillon S. Myer and American Racism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), 72-73.

- ↑ Myer, Uprooted Americans , 286.

- ↑ Hosokawa, Nisei: The Quiet Americans , 386.

- ↑ Philp, "Dillon S. Myer," 48.

Last updated March 26, 2024, 12:34 a.m..

Media

Media