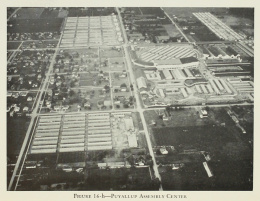

Puyallup (detention facility)

| US Gov Name | Puyallup Assembly Center, Washington |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | Temporary Assembly Center |

| Administrative Agency | Wartime Civil Control Administration |

| Location | Puyallup, Washington (47.1833 lat, -122.2833 lng) |

| Date Opened | April 28, 1942 |

| Date Closed | September 12, 1942 |

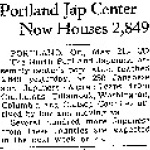

| Population Description | Held people from Seattle and Tacoma, Washington; also held some from Alaska. |

| General Description | Located on the Western Washington State Fairgrounds, 35 miles south of Seattle, Washington. |

| Peak Population | 7,390 (1942-07-25) |

| Exit Destination | Tule Lake, Minidoka |

| National Park Service Info | |

| Other Info | |

For two weeks beginning April 28, 1942, 7,390 prewar Nikkei residents from Seattle and rural areas surrounding Tacoma, and a handful of Alaska residents were forcefully removed from their homes by army troops and transported into the barbed wire confines of the Puyallup Assembly Center ("Camp Harmony"), located at the Western Washington Fairgrounds in the city of Puyallup (pop. 7,500), 35 miles south of Seattle. The last inmate departed the center on September 12, 1942.

Site and Facilities

Army officials selected the fairgrounds site, home of the annual Puyallup Fair since the turn of the century, because it possessed permanent facilities in good repair as well as upgraded power, water, and sanitary facilities capable of accommodating more than 5,000 people. More, it was located in proximity to the communities being removed.

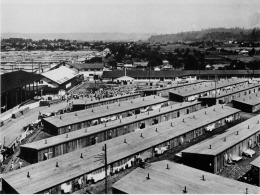

Encircled by Puyallup, the fairgrounds site covered 43 acres of lawn-covered fairways and parade grounds with more than 40 permanent buildings available for occupancy. Outside the northern and eastern boundaries lay three open parking lots, the largest with spaces for 7,500 automobiles. The main fairgrounds could accommodate 3,000 inmates while the 34 acres of adjacent parking lots provided room to house an additional 5,000.

Following signing of lease agreements, on March 29 fair officials assured the public the annual Puyallup Fair would take place on time in September 1942. In fact, the fairgrounds did not reopen to the public until 1946.

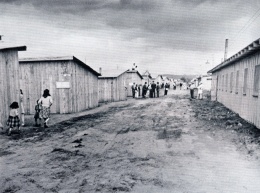

Most communal housing at Camp Harmony (a euphemism coined by army public relations officials days before the first Nikkei arrival and a name in common usage by camp survivors) was newly constructed. Family barracks arose atop mudsills set directly on the ground, each 20 feet in width and of variable lengths. Eight-foot high inner walls divided the long structures into multiple family compartments.

Construction on the former parking lots—Areas A, B, and C—provided each area with its own set of mess halls, latrines, showers, and laundry facilities. Area A, for example, with housing for 3,000 inhabitants, had six 40 x 100 foot mess halls, permitting 500 people at a single feeding. Three warehouses, two laundries, eighteen latrines, and six shower areas completed the plan. A firebreak provided an open area for athletic and other group activities. Finally, two manned watchtowers faced each other at the perimeter. Areas B and C, built to shelter 1,100 and 900 inmates, respectively, lacked the open spaces afforded Area A.

Because of the odd configuration of the fairgrounds proper with its existing structures and oval parade ground, Area D barracks varied in length. Open but damp space beneath the existing grandstand was converted into 105 bachelor "apartments."

Units within the new barracks each had a single window cut into an eight-foot back wall, while a windowless doorway on a ten-foot front wall opened out to face another barracks. Buildings took on an appearance of long sheds. Electrical wiring ran the length of every barracks, but each apartment had only a single socket hanging from the ceiling. In each living space a wood stove sat on common shiplap floorboards.

In all, allotting 50 square feet per person as planned, the new assembly center had a capacity of just over 8,000 individuals. Many inmates who later described their accommodations recalled them as unfit for families, "nothing more than a shed on a chicken ranch," or "rabbit hutches."

In Area D a 100-bed hospital was built to serve the medical needs of all inmates. Existing buildings were used as community halls, administration office space, and mess halls.

Camp Harmony's four geographically separated areas created an immediate problem for residents wanting to move between them to visit friends and relatives, conduct center business in Area D, or attend religious services and social events. Inter-area migration involved passing through a gate guarded by sentries and required crossing a city street with an escort. A clumsy operation had been devised where inmates gathered at the gate to be chaperoned across by inmate monitors. Restricted to individuals possessing work related or special passes or to those participating in organized events, crossing the street on a whim soon became impossible.

Life at Camp Harmony

Work opportunities opened up immediately for a minority of residents with special skills—barbers, cobblers, office clerks, food preparers, health workers, religious leaders. Volunteer opportunities for recreation, learning, and other community wide activities were later created by activists trying to simulate normalcy.

Food, which for the first three weeks consisted of Army "B" rations, gradually improved. The hospital, after a long delay, opened and took in obstetrics cases. Inmate carriers delivered mail to the barracks relieving patrons of the burden of walking to distribution points to collect their communications with the outside world. Volunteer work and recreation opportunities brought welcome relief from inactivity. And the weather, that had bedeviled the camp population with drenching rain throughout the entire moving-in period, began to improve.

The majority of residents awaiting an unknown transfer date to an unknown "relocation center" began to reconcile to the dullness of incarceration's daily routine. Adjustment was often most difficult among the youth, for whom boredom was a constant presence. One survivor recalled her experience as a teenager: "There was this space between the barracks. When it was really hot everybody would go to one side of this lane and lean against the building and just sit there. And later on in the day when the sun changed its course, we'd go to the other side."

Dissension

During the period leading up to its forced removal to Camp Harmony, the Nikkei community came under the leadership of Jimmie Sakamoto , a 40-year old Nisei journalist who earlier had helped advance Nisei interests using his Japanese American Courier newspaper as their voice. Sakamoto had access to City Hall and held the respect of uptown journalists from the mainstream media. With a hand picked cadre of friends and associates, most of them members of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), he led the community's response in the wake of Pearl Harbor and silencing of the community's Issei leadership. Later, army representatives asked him to lead his community into captivity.

Sakamoto's top down management style and handpicked lieutenants created almost immediate dissension in the community, which carried into the Camp Harmony experience. The group's new positions of authority led some of them to exercise old or discover new ways to intimidate others, show favoritism, and curry favor with center administrators.

Focus on the perceived unrepresentative and authoritarian Sakamoto and his council led center officials to accuse the Nisei-led group as arrogating power to themselves and usurping the authority of the army-run administration. As a result, after obtaining the approval of army headquarters in San Francisco, camp administrator J.J. McGovern dissolved all self-government activity. This experience may have led to a similar abolishment of self-government at other assembly centers.

Moving On

During May and June, departures from Camp Harmony for seasonal work leave, student resettlement, and repatriation totaled fewer than 100 people. An additional 196 volunteers left for Tule Lake on May 26 to help prepare for the arrival of its first inductees.

For the vast majority the mass transfer to Minidoka would begin August 12. The move to Idaho took place from August 9 through September 12 in 16 transfers by government-requisitioned trains. Each transfer included approximately 500 residents assigned to 11 passenger cars, accompanied by two baggage cars, two diners, and two Pullmans. The 30-hour ordeal took the migrants through the verdant landscapes of Washington and Oregon into desert country with its treeless aridity, which many had never seen.

As the last train departed Puyallup station on September 12 the Puyallup Assembly Center site became a temporary ghost town. A skeleton crew remained to sign off transfer of all properties and turn the keys over to army personnel. On September 30, 1942 the center site officially became attached to the Fort Lewis Ninth Service Command, which used it as a training facility until the end of the war.

In 1946 the Puyallup Fair once again took place after a four-year hiatus and has occurred annually down to the present day.

Remembering Camp Harmony

In 1978, 36-years after the Camp Harmony experience, an organized return to the former assembly center for a day of remembrance helped galvanize a Nikkei community poised to seek government redress for survivors of the incarceration experience.

At its annual convention in July 1978, a new generation of JACL national council members unanimously passed a resolution proposing legislation for a $25,000 individual payment and community trust fund. Local writer Frank Chin conceived of a Day of Remembrance to draw national attention to it. While researching a story about redress in Seattle, Chin and members of a newly formed Seattle Evacuation Redress Committee, helped organize the event. Word disseminated throughout the community encouraging participants to join a car caravan from Seattle's Rainier Valley to the Western Washington Fairgrounds on November 25, 1978 to: "Raise the flag over Camp Harmony to remember the years of hardship Japanese America endured to make the United States home for their parents, themselves, their children, and all the Nikkei generations to come."

More than 2,000 people attended festivities that included a potluck, talent shows, dance performances, and a Japanese American play. For the first time since the end of World War II survivors shared with each other and their children memories locked in their minds for a generation. Similar gatherings continue annually in the Pacific Northwest and other cities throughout the country.

Five years after this first Day of Remembrance, on August 21, 1983 Washington State Governor John Spellman and other state representatives active in their support of the redress movement helped dedicate a 10-foot cylindrical silicon-bronze sculpture by the famed artist, George Tsutakawa. Erected in the former Area D as a memorial to those incarcerated 40 years earlier, the ascending abstract figures depict, in the words of its creator: "Human people—old people, young people, men, women, children, even babies. They are gathered around in a circle holding each other in a happy relationship." The sculpture seems to convey that family ties, cultural values, and group cohesion enabled the Nikkei community to survive, to grow, and finally, to prosper.

Today the assembly center site continues to serve as a venue for exhibits, trade shows, and concerts, as well as the annual Puyallup Fair. Gone are all signs of barracks and many of the permanent buildings in Area D. Only the sculpture and two plaques in a courtyard outside the fair administration building remain to honor the 7,390 wartime Nikkei held there.

For More Information

Fiset, Louis. Camp Harmony: Seattle's Japanese Americans and the Puyallup Assembly Center. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2010.

Magden, Ronald E. Furusato: Tacoma-Pierce County Japanese 1888-1977. Nikkeijinkai: Tacoma Japanese Community Service, 1998.

Naske, Claus-M. "The Relocation of Alaska's Japanese Residents." Pacific Northwest Quarterly 74 (1983):124-32.

Last updated July 1, 2020, 8:20 p.m..

Media

Media