Beauty Behind Barbed Wire (book)

| Title | Beauty Behind Barbed Wire: The Arts of the Japanese in Our War Relocation Camps |

|---|---|

| Author | Allen H. Eaton |

| Original Publisher | Harper & Brothers |

| Original Publication Date | 1952 |

Beauty Behind Barbed Wire: The Arts of the Japanese in Our War Relocation Camps is a book by folk art expert Allen H. Eaton that was published by Harper & Brothers in 1952. The lavishly illustrated book was the first to examine the arts and crafts produced by incarcerated Japanese Americans—and one of the first books to examine any aspect of inmate life in the concentration camps. The foreword to the book was written by Eleanor Roosevelt , a friend of the author's.

Book and Author Background

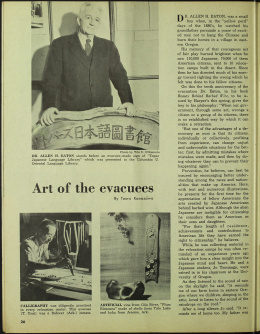

Known as the "dean of American crafts" and "acknowledged authority on the crafts of various ethnic groups in the United States," Allen Hendershott Eaton's life can be divided into two distinct parts. Born in 1878 in a log cabin in Union, Oregon, he became a powerful businessman, politician and university professor in his native state. However, in 1917, he was summarily fired from his faculty position in the School of Architecture at the University of Oregon due his attendance at a meeting of a pacifist and leftist organization that opposed U.S. participation in World War I. He was subsequently lost his state senate seat in the 1918 election. At age 40, he left Oregon for New York with his wife and two daughters and started over. This experience led his biographer, David B. Van Dommelen, to argue that his "deep interest in immigrants and discrimination almost makes us think that he too felt as though he were an immigrant. He understood their problems of being uprooted from their homelands, facing adversity, and attempting to find new directions for their lives." [1]

In 1920, he began working for the Russell Sage Foundation, one of the country's largest charitable foundations, where he would remain for the next 26 years. While there, he established himself as an expert on immigrant life and folk arts, mounting pioneering exhibitions and authoring landmark books including Immigrants Gifts to American Life (1932) and Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands (1937). In 1937, he also worked on the Rural Arts Exhibition in Washington, DC for the Department of Agriculture, which led to his becoming a friend and correspondent of Eleanor Roosevelt.

With the incarceration of West Coast Japanese Americans in concentration camps during World War II, Eaton approached Dillon Myer , director of the War Relocation Authority (WRA), the agency in charge of administering the camps, about the possibility of documenting the arts and crafts of the inmates and of putting together an exhibition of American ethnic handicrafts that might tour the camps. Though not unsympathetic, Myer declined WRA funding of Eaton's project, inviting him to seek other funders. The Sage Foundation also declined to fund the project, perhaps due in part to Eaton's being near retirement age by that time. In the meantime, he focused on a project on New England handicrafts that resulted in an exhibition that opened at the Worcester Art Museum in 1943. Still intrigued by the possibilities of the Japanese American project, he took a vacation in 1945 and visited five of the camps, identifying objects and photographers at those camps. He also found photographers and curatorial assistants at the other four camps to do the same. The photographers included WRA photographers such as Tom Parker , inmate photographers including Toyo Miyatake (who in addition to taking photographs at Manzanar, was dispatched to Poston and Gila River ), and local professionals from the area near specific camps. Eaton had in the meantime secured funding for the project from the Rockefeller Foundation, through the sponsorship of the Society of Japanese Studies, along with the Japan Society. Delayed from finishing the book due to work on other projects—his New England handicrafts book was published in 1949 and he went to Europe in 1950 as part of the Economic Co-operation Administration of the Marshall Plan—he finished the manuscript in 1951. Harper & Brothers, which had published his New England book, agreed to publish the Japanese American book once the Japan Society committed to buying enough copies of it. Beauty Behind Barbed Wire was published on the 10th anniversary of Executive Order 9066 , on February 19, 1952. Eaton was 73 years old by the time the book came out. [2] A second edition of the book appeared in 1955, with a new three-page postscript that adds information on the Evacuation Claims Act and the Immigration Act of 1952 . [3]

Book Overview and Reaction

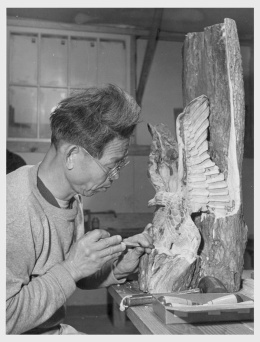

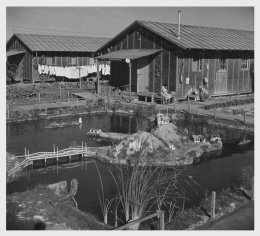

The core of the 208 page book is made up of 81 sets of photographs on odd numbered pages accompanied by Eaton's explanatory text on the facing even numbered page. The photograph pages—most consist of one large photograph, while others are sets of two or more related images—depict a wide range of creative expression from the WRA camps, ranging from gardens and other external and internal modifications of barrack living spaces to handicrafts, painting and sculpture and a few images of Japanese cultural activity such as bon dance or tea ceremony. Many of the images include camp inmates, whether artists at work, students in art classes, or people enjoying art displays. Eaton's accompanying text, which ranges in length from just a couple of paragraphs to a full page, generally provides the camp specific context of the depicted work along with his own observations, often drawing on and quoting from works on Japanese art and culture.

The core of the book is preceded by Eleanor Roosevelt's short (approximately one page) foreword and Eaton's introduction and prologue. Part II of the book includes "A Look Back: A Look Forward," Eaton's summary of the exclusion and incarceration, along with an annotated bibliography on Japanese Americans. Both Roosevelt and Eaton extol the work of the WRA, with the former first lady calling the agency "one of the achievements of government administration of which every American citizen can be proud." [4] Eaton's account of the exclusion and incarceration draws on the then current work on Morton Grodzins and Eugene Rostow , concluding that "This evacuation, regardless of its military justification, was not only, as is now generally acknowledged, a great wartime mistake, but it was the most complete betrayal, in one act, of civil liberties and democratic traditions in our history, and a clear violation of the constitutional rights of seventy thousand citizens." [5]

Beauty Behind Barbed Wire received a positive review from Richard L. Neuberger in the New York Times Book Review , though as was often the case in mainstream reviews of books on the incarceration, the review was as much of the events as of the book itself. [6] The reviewer for the Pacific Citizen praised Eaton's captions as where "the author does his greatest service." "Through these captions," wrote M.O.T., "the evacuees become real, their creations become symbolic of their spirit, which refused to wither in strange and stifling circumstances....It is the author's own sense of humanity and compassion that makes 'Beauty Behind Barbed Wire' an intensely moving and dramatic book." [7] In a lengthy review in College Art Journal , Wallace S. Baldinger criticizes Eaton for the "disjointed text not only by writing the bulk of it around the illustrations alone but by following in their choice and arrangement no apparent pattern." He also questions the emphasis of the Nisei's American citizenship on the one hand and viewing of the artwork as "a piece of Japanese society transplanted to America." [8] The book has been cited as a pioneering work on its topic in many subsequent books and articles on creative expression in the concentration camps. [9]

Find in the Digital Library of Japanese American Incarceration

This item has been made freely available in the Digital Library of Japanese American Incarceration , a collaborative project with Internet Archive .

For More Information

Eaton, Allen H. Beauty Behind Barbed Wire: The Arts of the Japanese in Our War Relocation Camps . Foreword by Eleanor Roosevelt. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1952.

Kanazawa, Tooru. "Art of the Evacuees." Scene , February 1952, 26–29.

Phu, Thy. Picturing Model Citizens: Civility in Asian American Visual Culture . Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012.

Van Dommelen, David B. Allen H. Eaton: Dean of American Crafts . Pittsburgh, PA: The Local History Company, 2004. https://archive.org/details/allenheatondeano00vand

Correspondence between Allen H. Eaton and Estelle Ishigo concerning Ishigo's assisting Eaton in the selection and photography of art at Heart Mountain for the book.

Footnotes

- ↑ David B. Van Dommelen, Allen H. Eaton: Dean of American Crafts (Pittsburgh, PA: The Local History Company, 2004), 64.

- ↑ This account of the book's background draws from Eaton's prologue to Beauty Behind Barbed Wire , David B. Van Dommelen's biography, and correspondence between Eaton and artist Estelle Ishigo (particularly Eaton's October 22, 1945 letter to Ishigo), who selected objects at Heart Mountain and arranged for their photography. Referenced on November 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Second Edition of 'Beauty Behind Barbed Wires' (sic) Published," Pacific Citizen , Dec. 16, 1955, p. 1; accessed online at https://pacificcitizen.org/wp-content/uploads/archives-menu/Vol.041_%2325_Dec_16_1955.pdf on Nov. 5, 2012. This article also includes the full text of the postscript, which lavishes praise on the Japanese American Citizens League for their postwar role.

- ↑ Eaton, Beauty Behind Barbed Wire , xi. She also suggests that the incarceration was partly for the protection of the inmates.

- ↑ Eaton, Beauty Behind Barbed Wire , 176.

- ↑ Richard L. Neuberger, "Flowers in the Desert," New York Times Book Review , June 15, 1952, p. 10. See also Lyman Bryson, "Exiled Art," The Saturday Review , June 7, 1952, pp. 42–43, accessed online at http://www.unz.org/Pub/SaturdayRev-1952jun07-00042a02?View=PDF on October 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Book Review: 'Beauty Behind Barbed Wire,'" Pacific Citizen , March 1, 1952, p. 5, accessed online at https://pacificcitizen.org/wp-content/uploads/archives-menu/Vol.034_%2309_Mar_01_1952.pdf on Nov. 5, 2012. The review is signed "M.O.T.," which is almost certainly Marion Okagaki Tajiri ; thanks to Greg Robinson for pointing this out.

- ↑ Wallace S. Baldinger , "Review of Beauty behind Barbed Wire : The Arts of the Japanese in Our War Relocaton Camps by Allen H. Eaton," College Art Journal 13.1 (Autumn 1953), 61–63.

- ↑ For instance, in a recent doctoral dissertation, Krystal Reiko Hauseur refers to it (along with another work) as "invaluable documents of the profundity of internment handicraft in the ten camps and re-envisioning its importance in creating an upcoming Nisei generation of Japanese American craft artists." Krystal Reiko Hauseur, "Crafted Abstraction: Three Nisei Artists and the American Studio Craft Movement: Ruth Asawa, Kay Sekimachi, and Toshiko Takaezu," Ph.D. dissertation, University of California at Irvine, 2011, p. 65.

Last updated Dec. 8, 2023, 7:10 p.m..

Media

Media