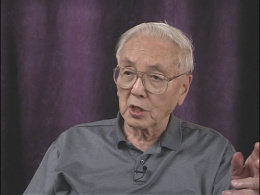

Bill Hosokawa

| Name | Bill Hosokawa |

|---|---|

| Born | January 30 1915 |

| Died | 2007 |

| Birth Location | Seattle, WA |

| Generational Identifier |

Bill Hosokawa (1915–2007) was a journalist and author who was a pioneering but controversial chronicler of the Japanese American experience whose Nisei: The Quiet Americans , the first popular history of Japanese Americans, was published in 1969. A longtime columnist for the Japanese American Citizens League's (JACL) Pacific Citizen newspaper, Hosokawa took a controversial stand against redress in the 1970s, but later supported redress and the presidential apology that came with the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 .

Before the War

Bill Hosokawa was born in Seattle, Washington, to Issei parents and raised in a Japanese-speaking household until he was forced to learn English in kindergarten. His teacher chose the name "William" for him because his Japanese name, Kumpei, was too difficult for her to pronounce. [1]

That introduction to a new language served Hosokawa well. He attended the University of Washington and graduated in 1937 with a degree in journalism. But before he graduated, he was told by his adviser, "I don't think there's a newspaper publisher in the country who would hire a Japanese boy." [2] The professor turned out to be right, so after college the young reporter took a job as a secretary at the Japanese consulate in Seattle, until a job opened up for an English-language editor for a new newspaper in Singapore. Hosokawa had just gotten engaged so he married his wife Alice in 1938, and the couple crossed the Pacific for his new job. The timing turned out to be unfortunate.

He reported in the Singapore Herald about the coming war in Europe as the Nazis dominated Germany's neighbors, and with tensions increasing in Singapore because of the Japanese military's push into Asia, Hosokawa sent Alice, who was pregnant with their first child, back to the U.S in 1940 to live with family while he stayed to pursue other newspaper work in Japan and China. During this period he wrote articles that were pro-Japanese. [3] But when Japan's relationship with the United States deteriorated in 1941 and war appeared imminent, he returned to Seattle to rejoin his wife. That was just a month and a half before the attack on Pearl Harbor .

Life During Wartime

When war broke out, Hosokawa was concerned about the fate of the 7,000 people in Seattle's Japanese community, and helped form the Emergency Defense Council, which served as a communications channel between the local government and the people of Japanese descent. After Executive Order 9066 was signed, Hosokawa, his wife and their son Mike were held at the state fairgrounds in Puyallup which served as the hastily prepared " assembly center ." The Emergency Defense Council then became a de facto administrative body for families at the center. The family lived in a stall with walls that didn't reach the ceiling, so they could hear noise from families at the far end of the barrack.

After three months, the Hosokawas were moved to a new concentration camp at Heart Mountain , near Cody in Northern Wyoming. Because of his training as a journalist, he became editor of the newspaper that sprang up to serve the inmates, the Heart Mountain Sentinel . During their stay in the camp, Hosokawa's mother-in-law was released from a Justice Department camp because of illness and came to live with them. After a little over a year in Heart Mountain, he was offered a job as a copy editor at the Des Moines Register newspaper. It took a couple of months to pass some hurdles in his background check (working for the Japanese consulate, and in Asia, probably made him appear suspicious), but he and his family were released in 1943 and he worked as a newspaperman for the duration of the war. His daughter Susan was born in 1944 in Des Moines.

Postwar Career as Journalist and Diplomat

In 1946, Hosokawa heard that a new editor and publisher, Palmer Hoyt, had taken over the Denver Post , which had been virulently anti-Japanese for years. The Post' s previous management had even manufactured a phony story about how food was being hoarded at Heart Mountain. [4] Hoyt had run the Portland Oregonian and had a reputation as a progressive and serious newsman. He was remaking the Post into a source for real journalism. Hosokawa applied for a job and Hoyt hired him as a copy editor.

The job started a decades-long career for Hosokawa, who served almost every major role in the newsroom, including foreign correspondent during the Korean war and later, Vietnam, and editor of the paper's popular Sunday magazine, Empire . He was the editorial page editor when he left the Post in 1984 and went to the competing newspaper, the Rocky Mountain News , as the reader's representative. He retired from newspapers in 1992.

During this entire period, Hosokawa kept a steady stream of columns flowing for the Pacific Citizen , the newspaper of the JACL. His commentary, titled "From the Frying Pan," began in 1942 and was popular with JACL members for his low-key and witty views on life as a Japanese American. Locally, Hosokawa shared his wry observations in a weekly column in Denver's Japanese community newspaper, the Rocky Mt. Jiho .

He also wrote eleven books, including Nisei: The Quiet Americans , one of the first popular accountings of the Japanese American experience. The book was published in 1969 and fit the spirit of the times, as the African American civil rights movement helped spark an interest in Asian American identity. But critics accused him of writing a book that served the " model minority " stereotype that had been invented during the civil rights movement to counteract the protests and activism of African Americans. [5] Critics argued that even the book's subtitle, "The Quiet Americans" embraced the JACL's decision to lead Japanese Americans meekly into incarceration, and was a statement of the "Old Guard" of Japanese Americans instead of representing the Sansei , or third generation's activist voice.

His other books include: Thunder in the Rockies: The Incredible Denver Post (1976), JACL: In Quest of Justice (1982), They Call Me Moses Masaoka (autobiography of JACL leader Mike Masaoka co-authored by Hosokawa, 1987) Old Man Thunder: Father of the Bullet Train (1997), Out of the Frying Pan (an autobiography and selection of columns, 1998) and Colorado's Japanese Americans: From 1886 to the Present (2005).

In addition to his journalism in Denver and his writing on Japanese American issues, Hosokawa became a champion for building business and cultural relationships with Japan. He helped found the Japan America Society of Colorado, and in 1974 he was named Honorary Consul General of Japan for Colorado, Utah and New Mexico until the Japanese government established an official consulate in 1999.

Reassessing Redress and Legacy

During the 1970s, Hosokawa was a public critic of the redress movement , saying at the time that asking for payment from the government "cheapened the sacrifice of the ordeal we went through" but then supported redress after the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians filed the fact-finding report that proved "a terrible wrong was done to us…. It was far different from people who had suffered saying 'give us some money for what we went through'." [6]

Because of his stature within the national Japanese American community and especially among JACL members, Hosokawa's initial resistance to redress caused a stir, but in retrospect his life was dedicated to civil rights and to Japanese Americans. Even during his imprisonment in the concentration camp at Heart Mountain, he wrote, in a "Frying Pan" column in the Pacific Citizen on July 2, 1942

…there is a persistent voice being heard from within this nation, representing but a small portion of its citizens and calling upon hatred, discrimination and prejudice because of race. This is the voice of people who would disenfranchise the Nisei, who would deport everyone of Japanese descent, who would deny the right of citizenship to those not of Caucasian blood, who would rescind the civil rights of American citizens as a gesture of American patriotism. These people are un-American." [7]

Hosokawa's legacy in Denver today is as a respected journalist, civil rights leader and diplomat. Dignitaries from the Japanese government (Ambassador to the U.S. Ryozo Kato) and Colorado Governor Bill Ritter attended the memorial service. The Denver Botanic Garden undertook a capital campaign and rebuilt its renowned Japanese exhibit as the William Hosokawa Bonsai Pavilion and Japanese Garden in 2012, and memorial busts of Hosokawa have been installed at both the Denver Botanic Gardens and the Denver Public Library.

For More Information

Hosokawa, Bill. Out of the Frying Pan . Colorado: University Press of Colorado, 1998.

Hosokawa, Bill. Nisei: The Quiet Americans . William Morrow & Co. 1969; University Press of Colorado, 2002.

Footnotes

- ↑ Bill Hosokawa, Out of the Frying Pan (University Press of Colorado, 1998), 2.

- ↑ Bill Hosokawa, Out of the Frying Pan (University Press of Colorado, 1998), 14.

- ↑ Greg Robinson, "Nisei Journalists and the Occupation of China: Buddy Uno and Bill Hosokawa Compared - Part 3 of 3," Discover Nikkei , May 4, 2012, http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2012/5/4/nisei-journalists-3/ .

- ↑ Bill Hosokawa, Out of the Frying Pan (University Press of Colorado, 1998), 61.

- ↑ Alice Yang Murray, Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress (Stanford University Press, 2007), 213-220.

- ↑ Densho oral history interview with Bill Hosokawa, Interview Segment 26, http://archive.densho.org/Core/ArchiveItem.aspx?i=denshovh-hbill-01-0026 .

- ↑ Bill Hosokawa, "Nisei Behind the Barbed Wire…" From the Frying Pan" column, Pacific Citizen July 2, 1942, 5.

Last updated July 29, 2020, 5:36 p.m..

Media

Media

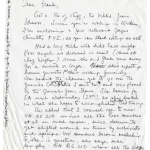

![Letter from Aochi to Mr. and Mrs. Okine, September 1, 1945 [in Japanese] Letter from Aochi to Mr. and Mrs. Okine, September 1, 1945 [in Japanese]](https://encyclopedia.densho.org/front/media/cache/c4/ff/c4ff19cadbdacb7250c9733f77476d42.jpg)