Buddhist Temple of Alameda

The Buddhist Temple of Alameda has been one of the pillars of the Japanese American community in Alameda since its founding in 1916.

Early History

On August 12, 1912, sixteen "Buddhist faithfuls" of the Nishi Hongwanji sect of the Jodo Shinshu denomination, led by Matsutaro Nakata, rented a storefront at 1630 Park Street in Alameda, establishing what would become the Buddhist Temple of Alameda. Predominant in the prefectures from which Japanese immigrants came, Nishi Hongwanji adherents made up the vast majority of Buddhists among Japanese Americans, an estimated seventy-five to ninety percent, organized since 1899 under the auspices of the Hokubei Bukkyo Dan or North American Buddhist Mission (NABM). Initially a branch of the Buddhist Church of Oakland, the growing Alameda temple rented a room in a mansion owned by Edward Kimberlin Taylor, a former mayor of Alameda, at 2325 Pacific Avenue and moved on April 8, 1914. The temple was formally established on January 4, 1916, as the Buddhist Temple of Alameda (BTOA), becoming the 21st temple to form as a part of the NABM during a period of rapid expansion that saw the NABM add at least one new temple a year until World War II. Rev. Shisei Shinohara became the new temple's first resident minister to serve the congregation that numbered around sixty. [1]

The new temple grew quickly and purchased the 7,125 square foot, three-story Taylor mansion and land on January 4, 1919, for $4,400, spending another $2,000 to remodel. The new space included a residence for the minister and his family. The temple was ultimately able to evade alien land laws by forming a non-profit corporation to own the building with young citizen Nisei members as trustees, with Taylor's assistance. The temple added a social hall and kitchen in 1925–26, and expanded by buying a neighboring private home to become the minister's residence, the second floor of the temple building being remodeled to create more meeting spaces. [2]

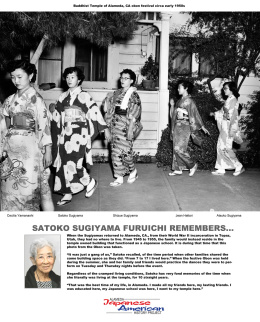

In the pattern of other NABM churches, the BTOA offered regularly scheduled religious services, as well as services connected to such special occasions as weddings, funerals, and memorial services. The BTOA formed a funjinkai (women's club), Young Men's and Young Women's Buddhist Associations modeled after the YMCA/YWCA, and ran a Japanese language school as it adjusted to the needs of a growing community with increasing numbers of American-born children. In the context of an often hostile outside society, Buddhist temples like Alameda's also "provided a friendly environment for an ethnic group that often encountered hostility from the society at large," according to Tetsuden Kashima, who added that they combined "secular activities with religious" in also hosting sports leagues, movie screenings, dances, and the like. The new social hall—with a seating capacity of three hundred that included a stage and kitchen—became the venue for many of these activities. In his memoir, Arthur Tadashi Hayashi recalls that the BTOA had more "exciting" activities than the Japanese Methodist church, citing kendo, judo, and sumo classes; Japanese movies; and graduation dances. [3]

By the 1930s, the BTOA expanded its services to serve the faithful in parts of southern Alameda County from San Leandro to Warm Springs that were not served by other temples, sending ministers, lay leaders, and Sunday school teachers to lead services and activities there. By 1936, the temple ran seven Sunday schools that enrolled 360 children and also hosted a champion girls basketball team. [4]

World War II

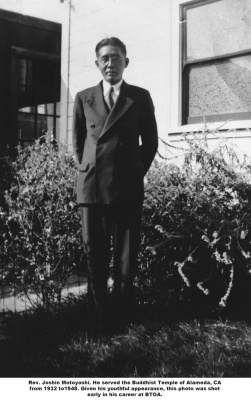

The outbreak of World War II brought the activities of the temple to a temporary halt with the forced removal of all Japanese Americans living on the West Coast. As was the case with the vast majority of Buddhist ministers, the FBI arrested Rev. Joshin Motoyoshi, BTOA's fourth minister, who had been at the temple since 1932, taking him first to the Fort McDowell detention facility on Angel Island and then to subsequent facilities in Lordsburg and Santa Fe, New Mexico. Paroled from Santa Fe, Rev. Motoyoshi was able to rejoin his family that included his wife, Yuriko, and six children, at the Topaz , Utah, concentration camp. At Topaz, he served as one of the ministers at the lone camp Buddhist church. The Motoyoshis remained at Topaz until September 1945, when they returned to Alameda. [5]

As with other members of the Japanese American community of Alameda, BTOA members ended up at various War Relocation Authority concentration camps due to the exclusion of Alameda Issei in February 1942 that scattered the community. In the absence of its congregation, the temple properties were used by the U.S. Navy as a training facility during the war years. [6]

After the War

As with many Japanese American churches and temples—including the Buena Vista United Methodist Church, the other major Japanese American church in Alameda—the Buddhist Temple of Alameda property was used as temporary housing for returning Japanese Americans starting in September 1945 and continued until 1947. With Rev. Motoyoshi's return, services at the temple gradually resumed. While the BTOA continued to serve southern Alameda County through the 1950s, demand for a separate temple grew in those areas, leading eventually to the founding of the Southern Alameda County Buddhist Church, which was dedicated in 1962 and formally established in 1965. In the meantime, the Japanese language school property behind the BTOA was torn down and replaced by an eight-unit apartment building that provided a revenue stream for the temple, and a new minister's residence was built in 1961. Threatened by plans for development in 1963, community opposition eventually scuttled the plans, saving the temple. [7]

Services at BTOA continued in the postwar years, adapting to a Nisei/Sansei congregation, offering regular services and special holiday services in Japanese and English and a fundraising carnival and food bazaar, along with various youth-oriented activities. To commemorate the the BTOA's 40th anniversary, young adult members created a Japanese-style garden that remains a focal point of the temple's grounds. The parsonage was replaced in 1961, and in 1980, the social hall was remodeled by removing the stage and upgrading the kitchen and restrooms. In 2010, the temple's treasured main altar piece was sent to Japan where it was restored, and the following year, the temple's 140-year old foundation was rebuilt. [8]

Several ministers led the temple in the postwar years. Rev. Eiyū Terao was a Kibei who had been at the San Francisco and Seattle temples before the war and helped establish the Spokane temple after the war. He led the BTOA from 1961 until his retirement in 1978. Rev. Zuikei Taniguchi served as the minister at Alameda from 1983 until 2017. Rev. Dennis Fujimoto has been serving as the resident minister since 2017. [9]

Over the years, the temple has changed in both physical structure and membership. While some members are descendants of the temple's original Sangha , the temple has also welcomed many new members and the diversity that they bring to the temple's community. All of these changes have positioned the temple to continue its mission into the future. [10]

For More Information

Buddhist Churches of America, Volume 1: 75 Year History, 1899–1974 . San Francisco: Buddhist Churches of America, 1974.

Kashima, Tetsuden. Buddhism in America: The Social Organization of an Ethnic Religious Institution . Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1977.

Williams, Duncan Ryuken. American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War . Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2019.

Footnotes

- ↑ "Buddhist Temple of Alameda," in Buddhist Churches of America, Volume 1: 75 Year History, 1899–1974 (San Francisco: Buddhist Churches of America, 1974), 184–86; Tetsuden Kashima, Buddhism in America: The Social Organization of an Ethnic Religious Institution (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1977), 5, 16, 226.

- ↑ "Buddhist Temple of Alameda," 186; "Celebrating 100 Years of Gratitude: Buddhist Temple of Alameda and Alameda Buddhist Women's Association, September 24 and 25, 2016, 26, Buddhist Temple of Alameda website, https://ttu.qna.mybluehost.me/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/100th-Anniversary-Booklet.pdf , accessed on Mar. 8, 2023.

- ↑ "Buddhist Temple of Alameda," 186–88; Kashima, Buddhism in America , 7, 23–24 36; "A Memoir, Arthur Tadashi Hayashi," Alameda Museum, https://alamedamuseum.org/Hayashi/ , accessed Feb. 14, 2023.

- ↑ "Buddhist Temple of Alameda," 186–88.

- ↑ "Buddhist Temple of Alameda," 182, 187; Yasutaro [Keiho] Soga, Life behind Barbed Wire: The World War II Internment Memoirs of a Hawai'i Issei (Translated by Kihei Hirai, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2008), 69–70, 103, 135; Topaz Final Accountability Roster, 108.

- ↑ "Buddhist Temple of Alameda," 187.

- ↑ "Buddhist Temple of Alameda," 187–88; Judy Furuichi interview by Virginia Yamada, Emeryville, California, Apr. 7, 2022, Alameda Japanese American History Project Collection, Densho Digital Repository; Kashima, Buddhism in America , 139–40; "Church History, Southern Alameda County Buddhist Church, https://sacbc.org/church-history/ , accessed on Mar. 29, 2023.

- ↑ Jane Naito electronic message, May 3, 2023.

- ↑ "Buddhist Temple of Alameda," 182, 187–88; Lenni Terao, "Rev. Eiyu Terao," Spokane Buddhist Temple newsletter, Feb. 2007, https://www.spokanebuddhisttemple.org/newsletters/2007/February2007.pdf , accessed on Mar. 10, 2023; "Celebrating 100 Years of Gratitude," 37; Sarah Tan, "Buddhist Temple of Alameda Welcomes New Minister," East Bay Times, Jan. 3, 2018, https://www.eastbaytimes.com/2018/01/03/buddhist-temple-of-alameda-welcomes-new-minister/ , accessed on Mar. 10, 2023; Upaya: Newsletter of the Buddhist Temple of Alameda, Aug. 2021, https://www.btoa.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/BTOA_2021_August_Upaya.pdf , accessed on Mar. 20, 2023.

- ↑ Jane Naito electronic message, May 3, 2023.

Last updated Dec. 13, 2023, 5:34 a.m..

Media

Media