Alameda, California

Since the early 1900s, the East San Francisco Bay city of Alameda has had a close-knit Japanese American community anchored by a Buddhist and a Methodist church and a cluster of Japanese owned businesses. Given its "strategic" location on Alameda Island, Issei in Alameda were forced to vacate in two stages in February 1942 scattering the roughly eight hundred Japanese American community members, who ended up going to different concentration camps. Though relatively few returned to Alameda directly from the concentration camps, the Japanese American community did return after the war. In recent years, various efforts have recognized and preserved the history of Japanese Americans in Alameda.

Early Years

The City of Alameda is mostly located on Alameda Island, which is just offshore and south of Oakland. Once a peninsula that was the ancestral home of the Ohlone people, a canal project finished in 1902 turned Alameda into an island that is connected to the mainland by several bridges. Much of the island consists of filled land. Large scale settlement began in the 1860s as transit options including ferries and train lines made the island accessible to both Oakland and San Francisco. Alameda was incorporated as a city in 1872. [1]

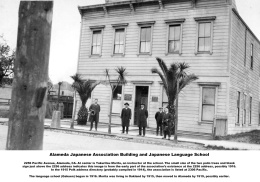

Among the pioneering settlers in Alameda were Japanese immigrants. Bay Area flower pioneer Hirokichi Hayashi arrived in 1889 and opened a flower and plant retail store, while Eisaburo Tomoeda opened a shoe repair shop in 1893 and other business including a tailor shop, Masataro Sato's grocery store and the Narahara Hotel on Park Street soon followed. The same year, the Gakuyu-Kai, a organization of Japanese school-boys formed in Alameda. With the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1894, the Aikoku Kyokai (Patriotic Society) formed. The Japanese population of Alameda grew from around fifty or sixty—most from Fukuoka Prefecture—to 325 by 1904. The Alameda Nihonjin-Kai ( Japanese Association ) formed in 1906, a Methodist Church that would become Buena Vista United Methodist Church in 1903, and the Alameda Buddhist Temple in 1916. [2]

Inevitably, anti-Japanese agitation followed. In addition to measures that Japanese immigrants throughout California and U.S. faced restrictions to further migration from Japan, alien land laws , and ineligibility to become naturalized citizens. There were Alameda-specific actions as well, ranging from a proposed 1910 city ordinance to ban Chinese and Japanese laundries in certain areas to acts of anti-Asian violence. [3]

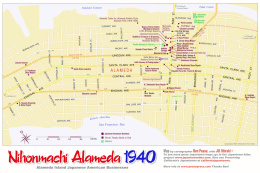

Alameda's Japanese community nonetheless continued to grow, reaching 500 by 1910, topping 600 by 1920 and 800 by 1930. The prefectural origin of community members continued to be largely Fukuoka, with some from Hiroshima as well. Many of the Issei were gardeners and domestic workers, but there were also a range of Issei-run businesses, especially flower shops/nurseries (eight, according to Zaibei Nihonjin Shi ), shoe repair shops (7), laundries (5), and barber shops/beauty salons (4). These businesses were clustered in an area bordered by Park Street, Santa Clara Ave., Walnut Street, and the Oakland Estuary, with most of them on Park Street. There were also some Nikkei commuters to Oakland or San Francisco who lived in the city, drawn to the stable community and good schools. In addition to the large presence of the two churches—each of whom operated a Japanese language school —there were kenjinkais , a Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) chapter that formed in 1932, and a popular Japanese American baseball team, the Taiiku-Kai that was part of Northern California Baseball Federation with teams from San Jose (Asahi), Salinas (Taiyo), Stockton (Yamato), and Sacramento (Mikado). Most Nisei attended either Porter of Haight grammar schools and Alameda High School. [4]

Wartime Incarceration

The outbreak of World War II brought uniquely difficult circumstances for the Nikkei community in Alameda. As with other locales, Issei community leaders were immediately rounded up, including Rev. Joshin Motoyashi of the Alameda Buddhist Temple, who was eventually interned at the Lordsburg and Santa Fe , New Mexico, internment camps. As with the better known case of Terminal Island in the port of Los Angeles, military authorities deemed Alameda to be a strategic location, given, among other things, the presence of the Alameda Naval Air Station which took up the western end of the island. Thus, even before Executive Order 9066 , Alameda Issei were excluded from the western part of the city on February 15, 1942, followed by an order for their departure from the entire city nine days later. Though Nisei were technically not affected, the fact that most Nisei were either children or dependents of their Issei parents effectively led to the early departure of most Alameda Nikkei. As a last act before his departure, Harry H. Kono, an Issei florist who had many connections among white civic leaders, donated $40 to the local defense council to show "appreciation" to the city that had "been very fine to us" and that had educated his children. His story received much play in the local press. A handful of older Nisei were able to stay in Alameda until being forcibly removed to Tanforan Assembly Center in early May. [5]

As with other excluded Japanese Americans—though months earlier—Alamedans often had to dispose of their homes and property at great losses. Most moved in with relatives or friends in surrounding areas. Churches and JACL chapters in neighboring communities such as Hayward, Mt. Eden, Centerville, and Irvington banded together to help the Alameda group. Mas Takano recalled that Alameda Japanese families "were living in the garage of some friends or some relatives, they lived in the garage or in the basement, and they said it was really tough," adding that "some people went to Stockton, San Jose, and way out to Hayward and Warm Springs, that was way out there, inaka [to the countryside], you know, they had to go inaka ." [6]

As a result of their dispersal, Alameda Nikkei ended up going to many different War Relocation Authority concentration camps, whereas most other communities were able to stay together in a single camp. Among those who listed Alameda as their prewar address on WRA forms, a little more than half went to Topaz, 19% went to Gila River , 9% each went to Heart Mountain and Tule Lake and about 12% to the other six camps combined. Siblings Cookie Takeshita and Mas Takano moved with their family to Cortez, a farming community in Merced County, after their eviction from Alameda, where a friend of their father's took them in. From there, they were removed to the Merced Assembly Center and Amache . The Yamashita family moved in with a relative in Sanger, from where they were removed to Gila River. Shigeki Sugiyama and his family moved to French Camp where a friend's farm had a vacant farmhouse, from where they were sent to Manzanar . Though he was later able to transfer to Topaz , he found that not many of his Alameda classmates were around since the Alameda people "were spread out all over." Kono and his family moved to Fresno before ending up at Gila River, from where they resettled in Denver . Even those who did go to Topaz found themselves separated from each other, spread out among many blocks, since they came from different parts of the Bay Area. [7]

The experiences of other Alamedans spanned the typical range of Japanese American World War II experiences. Already a well-known opera singer before the war, Ruby Yoshino moved to Denver to avoid incarceration and was able to continue her career. Howe Hanamura joined the army in February 1942, becoming the 22nd Alameda Nisei to be inducted, one of them being his older brother, Tates. Howe eventually became part of the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team . The rest of the Yoshinos and Hanamuras ended up at Topaz. Shuzo and Nellie Fumiko Takeda had two daughters and a son in Topaz before returning to Alameda, while Arthur Tadashi Hayashi resettled in Detroit before being drafted and serving in the Military Intelligence Service . Masato Maruyama was on the board of the Buddhist Church of Tanforan and the chair of the second Topaz Community Council before resettling in New York in January 1944. Rev. Shigeo Shimada of the Alameda Japanese Methodist Church was active in the Protestant Church of Topaz. Though threatened with physical harm as an accused "inu," he and his family—including a daughter born in Topaz—stuck it out, not leaving for San Francisco until May 1945. Rev. Motoyoshi was eventually paroled from internment and entered Topaz in March 1944, where he led Buddhist services with congregation members there. [8]

Rebuilding the Community After the War

According to WRA records, 211 Japanese Americans went to Alameda directly out of the concentration camps once the exclusion orders were lifted at the beginning of 1945, about a quarter of the prewar population. Both the Buddhist and Methodist churches served as hostels providing short-term housing to returnees. But due to ongoing housing shortages that plagued many West Coast cities, some remained in the churches for much longer. Sisters Judy Furuichi and Jo Takata recalled that their family lived in the basement of the Buena Vista Methodist Church until 1952, when they were finally able to buy a home down the street. "There was no bathroom, and we had to take our bath out of a tin pail," recalled Takata, who also noted that they were only able to buy their home via a non-Japanese American proxy who purchased it for them. Other former Alamedans returned after having resettled elsewhere from the concentration camps. Takeshi and Haruko Yamashita moved back from Madison, Wisconsin, in 1945, for example, purchasing a home across from the Buddhist Temple. Takeshi eventually became a mechanic for the county. Cookie Takeshita returned from Cleveland to rejoin her family and later worked for UC Berkeley. [9]

While overt discrimination against Japanese Americans declined after the war, as alien land laws and bans on naturalization were overturned and public perceptions of Nikkei became more positive thanks in large part to the highly publicized exploits of the Nisei soldiers , some remained. As in many areas, housing discrimination in particular in Alameda extended into the postwar years, exacerbated by large wartime increases in population. George Fukayama, a returning World War II veteran, tried to buy a home in Alameda with his wife, Akiko, "but a lot of the real estate companies would not show us homes outside of the boundaries for the Japanese. And I was told straight off the bat, says, 'Oh, we don't sell homes to Japs in that neighborhood.'" Mas Takano recalled housing discrimination stretching into the 1960s, with various areas off limits to Nikkei: "... you didn't show Japanese a house north of, I guess north of Lincoln Avenue, you can't show west of this street. You couldn't show anybody, Japanese in the east end..." He was finally able to buy a home in 1964, buying directly from a seller, avoiding real estate agents who were serving as gatekeepers. [10]

The two churches continued to be the centers of the community after the war. Though each had their own memberships, friendships and ties cut across religion. Rev. Michael Yoshii, the longtime pastor of the Buena Vista Methodist Church wrote that "[m]utual support was common among the Buddhists and Christians striving for survival in a postwar anti-Japanese society in North America." Both churches put on popular annual carnivals/bazaars along with various other events throughout the year. The JACL chapter was active in the early postwar years, and tanomoshi (rotating credit orgainzations) continued into the postwar years as well. In 1990, the Sansei Legacy Project started at the BVMC in the aftermath of the Redress movement , drawing Sansei from the Bay Area throughout the decade to talk about the long legacy of the wartime incarceration and the impact on succeeding generations. [11]

While some Nisei inevitably moved away after marriage and children, many retained a connection to Alameda, especially through continued participation with the churches. Shigeki Sugiyama remained a member of the Buddhist Temple of Alameda even after moving out, and he reported in a 2010 interview that "I consider Alameda my home but even though I live here in Richmond." [12]

As in other locales, a renewed interest preserving the history of Alameda's Japanese American community emerged in the aftermath of the Redress movement. An Alameda Japanese Community History Project conducted some oral histories and mapped the prewar Japanese community, eventually leading to an early 1990s museum exhibition on the history of Japanese in Alameda. In partnership with the local community, the Alameda Free Library did oral histories with Japanese Americans from Alameda, funded by a grant from the California Civil Liberties Public Education Program in 2010–11. More recently, a 2020 Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant funded a project to conduct additional oral histories and to digitize important community documents. [13]

While the historic Japantown in Alameda no longer exists, it is one of the few historic Japantowns in California for which the historic fabric still exists according to Jill Shiraki, the project manager of the Preserving California's Japantowns project. "The two churches look almost the same from before the war" and the city "still kind of feels like an old town." Perhaps in recognition of this, the City of Alameda and the two churches launched the Tonarigumi Historic Marker in 2022 that saw a series of historic markers placed at key sites documenting the history of Japanese Americans in Alameda, making the outlines of the old Japantown visible for a new generation. [14]

For More Information

Honor Bound: A Personal Journey . Documentary film produced and directed by Joan Safia, Flower Village Films, 1995. 55 minutes.

Honoring Alameda's Japanese American History . Documentary film, 2012. 65 minutes.

Footnotes

- ↑ Imelda Merlin, Alameda: A Geographical History (Friends of the Alameda Free Library, Alameda, California, 1977, Fifth (e-book) edition, 2019), https://alamedamuseum.org/ content/uploads/2019/11/Imelda_smallpics_4printing.pdf; "Alameda History," Alameda Museum, https://alamedamuseum.org/news-and-resources/history/ , both accessed on June 14, 2022.

- ↑ Zaibei Nihonjin Shi: History of Japanese in America , (Zaibei Nihonjinkai, 1940, translated by Seizo Francis Oka and edited by Koji Ozawa, Tim Yamamura, and Kaoru "Kay" Ueda), 49, 142, 197, 237, 284, 548–49.

- ↑ See for instance, The Evening Times Star , April 11, May 10, and Nov. 16, 1910.

- ↑ Zaibei Nihonjin Shi, 417, 426, 548–49; Cookie Takeshita interview by Brian Niiya, Segment 5, Emeryville, California, March 11, 2019, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho Digial Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1000/ddr-densho-1000-465-transcript-ebfa3a9a9c.htm ; [Sam Narahara], [Topaz] Community Analysis Section, "Alameda (A West Coast Locality Study)", p. 2, Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records, Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder H4.02, https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/k6hq45v3/?brand=oac4 , accessed on Sept. 6, 2018; Dennis Evanosky, "Japanese Once Disappeared, Today They Have Story to Tell," Alameda Sun , July 23, 2020, https://alamedasun.com/news/japanese-once-disappeared-today-they-have-story-tell , accessed on Feb. 3, 2023; Tamotsu Shibutani, "The Initial Impact of the War on the Japanese Communities in the San Francisco Bay Region: A Preliminary Report," [May 17,] 1942, p. 41, Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records, Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder A17.04, https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/28722/bk0014b1h0t/?brand=oac4 , accessed on Aug. 31, 2021; Shigeki Sugiyama interview by Richard Potashin, Segment 3, Richmond, California, Apr. 16, 2010, Manzanar National Historic Site Collection, Densho Digital Archive, https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-manz-1/ddr-manz-1-96-transcript-9b1c747b83.htm ; Shin Sekai , Sept. 5, 1932.

- ↑ San Francisco Chronicle , Apr. 29, 1942; "Buddhist Temple of Alameda," in Buddhist Churches of America, Volume 1: 75 Year History, 1899–1974 (San Francisco: Buddhist Churches of America, 1974), 182; [Narahara], "Alameda," 3–4; Oakland Post Enquirer , Feb. 5, 1942; San Francisco Chronicle , Feb. 8, 1942.

- ↑ [Narahara], "Alameda," 4; Mas Takano interview by Brian Niiya, Emeryville, California, Apr. 5, 2022, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho Digital Repository.

- ↑ Figures calculated by author based on WRA Final Accountability Rosters; Cookie Takeshita interview by Brian Niiya, Segments 3 and 7, Emeryville, California, March 11, 2019, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/media/ddr-densho-1000/ddr-densho-1000-465-transcript-ebfa3a9a9c.htm ; Shigeki Sugiyama interview, Segments 5 and 11; Gila River Final Accountability Roster, 112.

- ↑ Greg Robinson and Jonathan van Harmelen, "The Great Unknown and the Unknown Great: Japanese American Singer and Civil Rights Activist Ruby Hideko Yoshino," Nichi Bei Weekly , Nov. 5, 2020, https://www.nichibei.org/2020/11/the-great-unknown-and-the-unknown-great-japanese-american-singer-and-civil-rights-activist-ruby-hideko-yoshino/ , accessed on Mar. 28, 2023; Nichibei Shimbun , Feb. 11, 1942; Judy Furuichi interview by Virginia Yamada, Emeryville, California, Apr. 7, 2022, Alameda Japanese American History Project Collection, Densho Digital Repository; "A Memoir, Arthur Tadashi Hayashi," Alameda Museum, https://alamedamuseum.org/Hayashi , accessed on Feb. 14, 2023; Tanforan Totalizer , May 30, 1942; Sandra Taylor, Jewel of the Desert: Japanese American Internment at Topaz (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 181–82; Shigeo Shimada, A Stone Cried Out, the True Story of Simple Faith in Difficult Days (Valley Forge, Penn.: Judson Press, 1987), 125–28, 141; "Buddhist Temple of Alameda," 187; Topaz Final Accountability Roster.

- ↑ Figures calculated by author based on WRA Final Accountability Rosters; "Buddhist Temple of Alameda," 187; Judy Furuichi interview; Jo Takata interview, 2012, Alameda Japanese American History Project: Digital Stories Collection, Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/ddr-ajah-8-8/ ; Karen Morioka interview, 2012, Alameda Japanese American History Project: Digital Stories Collection, Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/ddr-ajah-8-4/ ; Cookie Takeshita interview, Segment 16.

- ↑ George Fukayama interview, 2012, Alameda Japanese American History Project: Digital Stories Collection, Densho Digital Repository, https://ddr.densho.org/ddr-ajah-8-1/ ; Mas Takano interview.

- ↑ Michael Yoshii, "The Buena Vista Church Bazaar: A Story within a Story," in People on the Way: Asian North Americans Discovering Christ, Culture, and Community , ed. David Ng (Valley Forge, Penn.: Judson Press, 1996), 56; "Buddhist Temple of Alameda," 188; Pacific Citizen , June 23, 1951 and Dec. 19, 1952; Annie Nakao, "Asian Pacific American Heritage Month," San Francisco Chronicle , May 26, 1996, https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/ASIAN-PACIFIC-AMERICAN-HERITAGE-MONTH-3140782.php , accessed on Mar. 28, 2023; author phone interview with Jill Shiraki, Mar. 24, 2023.

- ↑ Shigeki Sugiyama interview, Segment 4.

- ↑ Michael Yoshii, "Japanese American Bazaar Tradition & Racial Ethnic Identity," in Doing Theology with the Festivials and Customs of Asia , ed. Joseph Patmury and John C. England (ATESEA Occasional Papers No. 13. N.p.: ATESEA, 1994), 89; California Civil Liberties Public Education Program, FY 98–99 through FY 10–11, https://www.library.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/CCLPEPGrantsFY98-99%20thruFY10-11.pdf ; "Funded Projects," Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program, https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1379/funded-projects.htm .

- ↑ Jill Shiraki interview; "First Alameda Japantown Historic Marker Unveiling Takes Place Thursday," Alameda Sun , Nov. 15, 2022, https://alamedasun.com/news/first-alameda-japantown-historic-marker-unveiling-takes-place-thursday , accessed on Feb. 2, 2023.

Last updated Nov. 30, 2023, 6:34 p.m..

Media

Media