Topaz

This page is an update of the original Densho Encyclopedia article authored by Michael Huefner. See the shorter legacy version here .

| US Gov Name | Topaz Relocation Center |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | Concentration Camp |

| Administrative Agency | War Relocation Authority |

| Location | Delta, Utah (39.3833 lat, -112.7167 lng) |

| Date Opened | September 11, 1942 |

| Date Closed | October 31, 1945 |

| Population Description | Most of those held in Topaz were from the San Francisco Bay area: Alameda, San Francisco, and San Mateo Counties in California. |

| General Description | Located at 4,600 feet of elevation in west-central Utah, Topaz was set in Millard County 16 miles from the town of Delta, 125 miles southwest of Salt Lake City. Topaz Mountain was 9 miles northwest. The 19,800 acres of extremely flat terrain were within the Sevier Desert. Dust was a major problem. Temperatures range from 106 degrees in summer to below zero in winter. Vegetation is mainly high desert brush. |

| Peak Population | 8,130 (1943-03-17) |

| National Park Service Info | |

| Other Info | |

The "Central Utah Relocation Center"—more popularly known as Topaz—was located at a dusty site in the Sevier Desert in central Utah. The second least populous of the WRA camps (after Amache ), Topaz had a peak population of 8,130 inmates. Topaz had one of the most urban and homogeneous populations with nearly its entire inmate population coming from the San Francisco Bay Area. Topaz is perhaps best known as the site of the fatal shooting of an inmate by a sentry in April 1943 and the inmates protests that took place in its aftermath. There was also significant protest against registration in the spring of 1943 and of a variety of labor disputes. Topaz was also known for its art school, which included a faculty roster of notable Issei and Nisei artists. The Topaz Museum, which opened to the public in 2015, is located in nearby Delta, Utah, and today owns all of the land on which the camp had once been built.

Pre-History and Geography

Topaz was located in Millard County 135 miles south of Salt Lake City. The closest town—and the place where inmates arrived via train—was Delta, sixteen miles southeast by car. The camp site was at an average elevation of 4,560 feet and was surrounded by mountains; one of them, Topaz Mountain, twenty-five miles northwest of the center of the camp, gave the camp its popular name. While historic average temperatures in the area were 26° in January and 74° in July, there were large daily swings. The first winter was considered to be "mild," yet saw a low of -9° in January. Mild or not, the weather that first winter combined with a shortage of coal and stoves and a population unprepared for such weather led to much disruption of camp life with school and work days limited to just the warmer parts of the day. Temperatures in the summer of 1943 saw 100° for five straight days including a high of 105°. Annual precipitation in the area was less than seven inches a year. When it did rain or snow, the alkaline soil turned into a sticky mud. [1]

Based on both contemporaneous and retrospective accounts, however, the most severe environmental condition was the dust storms, bad even by the standards of other WRA camps. Tony O'Brien, the acting project attorney, wrote in a November 1942 memo that the "dust storms are much worse than those encountered at Minidoka . The dust is more powdery in texture and penetrates every crevice on the project." Maxim Shapiro, a visitor to the camp, wrote of the dust in December 1942 that "no one who has not seen it can imagine its ill effects. It penetrates everything—it fills your mouth, nostrils, the pores of your skin, your clothing—and all efforts to keep yourself or your room clean are just futile efforts..." "We could barely see one inch ahead of us," wrote JERS fieldworker Doris Hayashi of a dust storm in November 1942. "It swept around us in great thrusting gusts, flinging swirling masses of sand in the air and engulfing us in a thick cloud…," wrote Yoshiko Uchida in her memoir. [2]

The site of the camp was on land that had been ancestral to the Ute people. Prior to World War II, it was sparsely populated with Mormons being the largest group. There was a relatively small Japanese American community in Utah centered in Salt Lake City, along with a handful in Millard county. Once a successful farming area, the area had become depressed in the 1920s due in part to water shortages, various crop failures, and difficulty in preparing the land. Many farmers lost their land to Millard County due to delinquent taxes. In this environment, the federal government purchased some 19,000 acres from a combination of private owners and local government. About 3,000 acres were obtained by eminent domain. The site fit many of the criteria set by the federal government for a concentration camp in that it was far from populated areas or military installations but relatively accessible by rail and had the support of most of the local population who saw the camp as a vehicle for land development and water access. [3]

The principal contractor for Topaz was Daley Brothers, a San Francisco firm that utilized various subcontractors from Utah and California. A crew of eight hundred began construction of the camp on July 10, 1942. It was still very much under construction when the first inmates arrived on September 11. [4]

Layout and Physical Characteristics

Topaz was laid out in a rectangular grid, seven blocks wide by six blocks long, with the blocks numbered from one to forty-two. The four blocks in the center (17, 18, 24, and 25) were left empty for a planned high school; when the temporary high school that was set up in regular barracks in Block 32 became permanent, the center area became a "central plaza" that eventually included an auditorium, church buildings, a sumo ring, and other communal spaces. Blocks 15 and 21 were left vacant to be used as recreational areas and Block 2 was used as housing for WRA personnel. Inmates lived in the remaining thirty-four blocks. Barracks within a block were numbered from one to twelve beginning at the northwest corner of the block, and individual "apartments" were given letters A through F. Camp addresses were the block number, barrack number, and unit letter, e.g. 7–2–C. [5]

The WRA administration area was on the northern boundary of the camp and included fifteen buildings. The military police area—which along with the fence was under the separate jurisdiction of the army—was in the northeast corner of the camp and included thirty buildings. The hospital area was just west of the MP area on the north border of the camp and included seventeen buildings. The administrative area was near the main gate, and administrative housing and twenty warehouse buildings were west of that area. The entire complex—with the exception of the MP area—was surrounded by a barbed wire fence with seven watch towers on three sides of the camp; the towers on the southern and western sides of the camp were about a quarter mile beyond the barracks. The fence was in the process of being built as inmates started to arrive and was completed by the end of 1942. Though there was no mass protest about the fences as at some other camps, inmates still found them insulting. "The idea of a barbed wire fence being constructed here is the most aggravating situation," wrote JERS fieldworker Doris Hayashi in an October 1942 diary entry. Ninety-eight MPs arrived on September 8, 1942, and as many as 150 were stationed at Topaz at its peak. [6]

Most inmates arrived by train at the Delta, Utah, station and were transported to the camp by Utah Parks Co. busses and trucks. After the first "volunteer" group, succeeding groups were greeted by enthusiastic inmate greeters, a Boy Scout drum and bugle corps carrying a sign reading "Welcome to Topaz—Your Camp," and greetings by Camp Director Charles Ernst and other WRA staffers. [7]

Unfinished

Inmates arrived to an active construction site. "As of September 30, the project site was a scene of construction, excavation and dust," wrote Reports Officer Irvin Hull. "Nearly all project buildings… were still under early stages of construction," he added, and "[s]everal blocks of barracks were either not started or were still under construction." Inmates who arrived at the end of September and early October fared the worst. The relatively fortunate ones were taken in by friends or family members; other families were doubled up with strangers or put into barracks that were too small for them. Still others ended up sleeping in mess halls, the hospital building or other "emergency quarters." Perhaps the worst off ended up in unfinished barracks that lacked roofs, mattresses and blankets. After a visit to Topaz, WRA Reports Division Chief John Baker wrote that "one or two nights new arrivals had to stay up all night—huddled around stoves in recreation halls." In a 1944 interview, Aiko Maruoka recalled arriving in barracks that lacked roofs and electricity and being so "exhausted by the trip so that we slept right on the floor because we couldn't wait that late." "Temporary transformers proved inadequate to carry the load placed upon them by an increased populace and fuses blew out three nights consecutively cutting off lights and water," wrote Hull in an October 9 report. [8]

While inmate laborers slowly finished up the barracks and communal facilities such as school and hospital buildings, conditions slowly improved. However, the pace of "winterizing" did not keep up with temperatures that had fallen as low as 10° by the end of October, as many wall boards and stoves had not been installed by then. To make matters worse, a coal shortage stretched into November even for those who had stoves. A company that had been contracted to supply 25,000 tons of coal beginning on October 1 had by October 23 delivered just forty tons—less than one percent of what they had promised—forcing administrators to scramble for other suppliers. The lack of coal disrupted much camp activity, as school days were shortened or canceled and meetings scheduled around when there was heat. Showers were limited to a two-hour window in the evening. Inmate labor was compelled to aid in the delivery of coal from a mine over 150 miles away. In the meantime, inmates hoarded coal, taking from supplies in other blocks and even began to raid lumber piles. The coal supply finally began to stabilize towards the end of November. [9]

As at other camps, inmates did their best to improve conditions. Having experienced chaotic raiding of scrap lumber piles at Tanforan , inmate leaders tried to organize lumber distribution through block managers. This proved largely unsuccessful as lumber raids continued, even with guards assigned to watch the piles. Inmates used the wood to build furniture and other necessities. Visitor Maxim Shapiro wondered "how, with primitive tools and out of only scraps of lumber, they succeeded in fashioning these pieces." Some dug out "basements" under their barrack rooms that proved to be warmer in winter and cooler in summer. Muddy walkways were "paved" with gravel. Others tried to plant flowers and other decorative plants in front of their barracks, or made even more elaborate gardens that included ponds. Inmate landscapers replanted trees and shrubs found on land around the camp and also worked with administration to bring in purchased and donated trees and other flora to help beautify the center. While some of these efforts succumbed to the combination of alkaline soil, heat and wind, others endured. [10]

Blocks/Barracks

As of July 1943, there were thirty-four residential blocks; two of these (Blocks 8 and 41) were actually half blocks, with the other halves used as elementary schools. Each block had twelve barracks that were 20 x 120, along with a mess hall (40 x 120), an H-shaped bath house/latrine/laundry building (two 20 x 100 buildings connected by a 20 x 20 segment), and a recreation hall (20 x 100). In most blocks, the barracks were divided into six units: two rooms each of dimensions 20 x 16, 20 x 20, and 20 x 24. Because there were more small families requiring the smallest rooms then had been anticipated, some of the last built blocks (including 33, 34, 40, and 41) were adjusted so that barracks had two large 20 x 28 rooms and four of the 20 x 16 units. Even with this adjustment, some smaller families had to be doubled up, or had to have barrack units further subdivided. Unlike many other WRA camps, there was no dedicated bachelor area or bachelor barracks; instead, singles were scattered throughout the camp in various combinations in regular barrack units. [11]

The barracks were built of pine and elevated from the ground on stacked wood scraps with no footings or foundations and no insulation, though gypsum board inner walls were added later. Black tar paper was used on the outside walls and roofs were asphalt, while floors were eventually covered with Masonite. Each unit had a pot-bellied coal burning stove; cots, mattresses and blankets; and three to five windows, depending on the size of the room. John Embree , the head of the Community Analysis Section in the WRA Washington, D.C. office, reported that the rooms did not retain heat as well as those at Amache, whether because the stoves were less efficient or the barracks less well insulated. There were three entrances to each barrack building, each of which opened into a small hallway from which doors led into the two units on either side. [12]

Latrines

The men's and women's bathroom facilities were in a central building in each block that also included the laundry room and coal-fueled boilers to heat the water. The latrine included flush toilets—ten in the men's section along with six urinals and fifteen in the women's section—that were partitioned, but did not include doors. They also did not initially include toilet seats, which were installed in late October. The men's section included twelve showers, the women's eight showers and four bath tubs, though there may have been some variation from block to block. As with the toilets, they were partitioned but not did not include doors. The shower floors were concrete and sloped to a drain. In her memoir, Toyo Suyemoto wrote that inmates would arrange for a friend to shower in the opposite stall so as to minimize embarrassment. Suyemoto also recalled drawing an audience of other women when she bathed with her baby in one of the tubs. Each bathroom unit also included ten sinks each for men and women. As with the toilet seats, mirrors weren't installed until later. Water quality was apparently poor; Minoru Kiyota wrote in his memoir that it was "so lukewarm and salty that I gagged on it." [13]

Mess Halls

Each block mess hall was a in building that was essentially a double wide barrack that could feed the entire block population of 250 to 300 in one seating. Described as "barn-like on the inside" by Toyo Suyemoto, the mess halls had the cooking area and serving counters at one end, with the rest devoted to communal tables at which the inmates ate. Depending on the block and time period, inmates either lined up for food cafeteria style, or were served in communal platters family style, with the former becoming prevalent. Because some mess halls developed a reputation for having particularly good or bad food resulting in uneven numbers going to each mess hall, a ticket system was developed by the end of November, limiting inmates to their assigned mess hall. Breakfasts, lunches, and dinners were served at specific times. The mess hall in Block 1 was larger, 40 x 172 (the same width but substantially longer than other mess halls), and was used for dances and other events/assemblies prior to the construction of the auditorium in December 1943. [14]

Assessment of the food varied. Quality and quantity was clearly poor at first and improved to some degree later on, particularly as produce and meat from Topaz's agricultural operations began to appear and as the inmate cooks improved. In a December 1942 report, Maxim Shapiro wrote that "[t]he food, as I heard from dozens of people, was at first both inadequate and insufficient—complaints voiced chiefly about the lack of foods containing proteins." In a November 1942 letter, Tom Yamamoto complained to friends on the outside that "the food is too scanty for a wolf such as I," adding that as he wrote, "my stomach is gurgling with hunger." Suyemoto described one meal of beef kidneys and cabbage: "… as the odor spread outside, those of us in line looked at one another and asked, 'What is that?' Not even the very hungry would try this combination." [15]

In the spring and summer of 1943, the camp was unable to purchase sufficient meat due to outside shortages, and began serving a succession of organ meats—livers, hearts, tripe, etc.—that most inmates found unpalatable. Widespread complaints followed, including appeals to the Spanish Consul and the State Department, and calls for the firing of the chief steward. The situation was eventually resolved when the camp farming operation began to deliver beef and pork to mess halls in August 1943. [16]

Population Characteristics

The population of Topaz was an unusually homogeneous one, consisting almost entirely of Japanese Americans from the San Francisco Bay Area who had gone first to the Tanforan Assembly Center. As such, it was among the most urban of all of the camps, with nearly 73% of the population coming from cities with populations of over 25,000, the third highest ratio of the WRA camps, behind only Manzanar and Minidoka. Fewer than 250 Topaz inmates were farmers. The peak population of Topaz was 8,130, on March 17, 1943. According to WRA records, there were 384 births, 136 marriages, and 139 deaths. [17]

The first group to arrive at Topaz consisted of 214 "volunteers" from Tanforan. This group was selected to include a cross section of people to help set up key areas of the camp, including the hospital, administration offices, mess halls, and recreation programs. Most of this group were Nisei young men (though about forty were women) who averaged about thirty years of age. One of this group, Fred Y. Hoshiyama , was also a JERS fieldworker who summarized both the altruistic and selfish motivations for being a "volunteer." "I am challenged and the adventurous feeling that we are to help set the camp for the rest of the camp gives our mission a double edge of keenness," he wrote. But on the other hand, "[t]here is an added incentive in being trail blazers for we can get better jobs, more scrap lumber and get to know the camp situation and administrative staff much better." Six days later, regular groups of about five hundred began to arrive daily from Tanforan for the next eight days. After a break of four days, the arrivals continued into early October, with conditions deteriorating for the later arriving groups as noted above. [18]

| Assembly Center | Arrival Date | Number |

| Tanforan | Sept. 11 | 214 |

| Tanforan | Sept. 17 | 502 |

| Tanforan | Sept. 18 | 482 |

| Tanforan | Sept. 19 | 511 |

| Tanforan | Sept. 20 | 498 |

| Tanforan | Sept. 21 | 505 |

| Tanforan | Sept. 22 | 520 |

| Tanforan | Sept. 23 | 500 |

| Tanforan | Sept. 24 | 516 |

| Tanforan | Sept. 28 | 525 |

| Tanforan | Sept. 29 | 514 |

| Tanforan | Sept. 30 | 516 |

| Tanforan | Sept. 31 | 513 |

| Tanforan | Oct. 2 | 522 |

| Tanforan | Oct. 3 | 527 |

| Tanforan | Oct. 15 | 308 |

| Santa Anita | Oct. 7 | 550 |

Source: John L. Dewitt, Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Army, Western Defense Command), 282–84.

One of the last groups to arrive was the one from

Santa Anita

, a group of about 550. This was a group from San Francisco that had been the first to be removed from the Bay Area in April 1942 before Tanforan was ready, necessitating their incarceration down south. Their long incarceration at Santa Anita along with the miserable conditions they faced as late arrivals at Topaz led to their being viewed by other inmates as having "a cocky attitude" and having "a chip on their shoulder." Community Services Chief Lorne Bell described them as "something of a problem, reflecting to some degree the very unfortunate conditions which must have prevailed at that center [Santa Anita]." Their incarceration with Los Angeles people also seemed to have changed them in the view of the Bay Area people. Hoshiyama described their arrival with some degree of bewilderment:

Many of the young nisei boys who were conservative dressers came off of the bus in "zute (sic) suits" and other flashy dress wear. The girls wore their hair in styles different from the Tanforan group ala Hollywood glamour styles—either long like Veronica Lake or short and put up. Their language, their attitudes, their mannerism changed to the extent that It was easily discernible and many of the Tanforan girls and boys expressed surprise as well.

The Santa Anita group was housed in Blocks 33, 34, and 40 and apparently remained somewhat distinct from the rest of the camp population. [19]

Another distinctive group at Topaz was a continent of 226 from Hawai'i that arrived in March of 1943 and were housed in Block 1. Most—176—were single men, most of them Kibei. Inmates and WRA staff went through great efforts to welcome them upon their arrival. Many had been interned at Sand Island previously or were family members of such internees. Most of them eventually ended up going to Tule Lake after segregation and many went on to Japan. Topaz also received a substantial contingent of "loyal" inmates from Tule Lake in the fall of 1943 as part of the segregation process; this group will be discussed at greater length below. [20]

Relationship to Local Community

Based on both contemporaneous and retrospective accounts, relations between Japanese Americans from Topaz and residents of Delta, the nearest town, were relatively positive compared to the situation at other WRA concentration camps, with some crediting the prevailing Mormon faith of the townspeople. WRA Reports Division Chief John Baker wrote of the belief that "Mormons in near-by areas and the Church members in general are sympathetic and understanding because they too have experienced oppression and evacuation." "We experienced none of the really nasty episodes that plagued some of the other centers," recalled teacher Eleanor Gerard Sekerak, while Doris Hayashi wrote in her diary that the "people in Delta are rather friendly." In a 1978 interview, Kinichi Kimbo Yoshitomi noted other reasons for the friendliness, recalling that inmates "brought a lot of business, and then it helped them with their sugar beet farms and milling." Indeed, some Topaz inmates worked for locals, whether as housekeepers or helping with farm work. But Project Attorney Tony O'Brien, who also worked at Minidoka, thought that because there was less contact between inmates and locals at Topaz vs. Minidoka due to more stringent rules on obtaining passes and the fact that fewer inmates did outside farm work, that "the feeling was stronger against the evacuees in this area than in Idaho." As time went on, interactions between inmates and Delta residents grew, as civic clubs visited Topaz and Topaz High School sports teams played against local high schools. [21]

While inmates at Topaz did do outside farm work as at many other WRA camps, the numbers were likely fewer for a number of reasons. Recruiters for local sugar companies visited the camp within days of the inmates' arrival and some were at work by the end of September 1942, with some 600 having taken on outside farm work by the end of October. Sugar companies and local farmers wanted more laborers and "considerable ill will seems to have been developed because no larger numbers have volunteered." But as noted above, the Topaz population was an urban one with few experienced farm workers, which undoubtedly was a factor in the relatively low numbers. Some farmers also complained about paying going wages to such inexperienced and unskilled workers. [22]

Another factor was the poor reception some farm workers received. One of the areas where laborers were most needed was in Utah County, where the WRA set up a housing camp in Provo that could house up to 400 Japanese American workers. Some of the workers reported that stores and restaurants wouldn't serve them and that locals harassed them on the streets. In October 1943, some local youths even fired shots into the labor camp while the inmates were present. They refused to return to work until their safety could be guaranteed. Armed guards were quickly brought in, and the inmates did go back to work. [23]

Personnel

Topaz had two project directors: Charles Ernst (opening to May 1944) and Luther Hoffman (May 1944 to closing). Ernst, in his mid-fifties, had a varied background in social welfare work and industry. A 1909 graduate from Harvard, Ernst worked for the South End House in Boston both at the beginning and end of his career as well as for the Department of Public Welfare in the state of Washington in the 1930s and for the American Public Welfare Association and National Red Cross in Washington, D.C. and San Francisco prior to joining the WRA. He spent much of the 1920s with the Hood Rubber Company in Seattle. JERS fieldworker Fred Hoshiyama described him as "a huge man with a very distinguished appearance" who "looks much younger [than his age] and exerts tremendous energies as he carries on his duties." While many former inmates remembered him fondly some co-workers remembered him as status-conscious, distant from inmates, and "cold and standoffish." [24]

After Ernst left Topaz on May 24, 1944, Hoffman took over as director. Born in 1898 and a graduate of the University of Arizona, he had worked for the Office of Indian Affairs in Arizona and for the Soil Conservation Service and was assistant supervisor of the Navajo Reservation before being tapped by the WRA. He began as the chief of community management at Gila River and was subsequently promoted to deputy director there and then as assistant chief of the Relocation Division in the Washington D.C. office, before being selected by WRA Director Dillon Myer to succeed Ernst. In his personal narrative, Hoffman suggests that he put his foot down in defining the limited reach of the inmates through the Community Council. Teacher Eleanor Sekerak—who spoke highly of Ernst—described Hoffman as a typical OIA "bureaucrat who saw Topaz as just another Indian reservation to be pacified." [25]

Other Topaz staffers who seem to have been well-liked by inmates included Chief of Agriculture and later Chief of Operations Roscoe Bell, Co-op head Walter Honderich, and Community Welfare Head George Lafabregue. Bell brought his wife and four children with him to Topaz and attended church services with the inmates and sent his children to Topaz schools. [26]

In the early months of Topaz, Project Director Ernst and Assistant Director James F. Hughes oversaw twelve division chiefs and sixteen section heads as follows:

Project Director: Charles F. Ernst

Assistant Project Director: James F. Hughes

Chief, Public Works, Division: Lee J. Noftzger

Head, Irrigation and Conservation Section: Henry R. Watson

Head, Construction Section: Mulford M. Hutchinson

Chief, Agricultural Division: Roscoe Bell

Head, Agricultural Production Section: William C. Farrell

Chief, Community Services, Division: Lorne W. Bell

Head, Education Section: John C. Carlisle

Head, Community Welfare Section: George Lafabregue

Head, Community Activities Section: (Miss) E. Minton

Chief, Internal Security: Ralph B. Fridley

Chief, Community Enterprises: Walter W. Honderich

Chief, Project Reports Division: Irvin Hull

Chief, Fire Protection Division: Samuel V. Owen

Chief, Administrative Division: Gilbert L. Niesse

Head, Procurement Section: William Hunter

Head, Property Control & Warehouse Section: K. W. Scoopmire

Head, Budget & Finance Section: Leon Burnham

Head, Office Service Section: Adrian H. Altvater

Chief, Employment and Housing Division: Claude C. Cornwall

Head, Quarters Section: Arthur Eaton

Head, Placement Section: James M. Jennings

Head, Occupational Coding and Records Section: none

Chief, Transportation & Supply Division: Roy Potter

Head, Motor Pool Section: Carl Rogers

Head, Mess Management Section: Brandon Watson

Chief, Maintenance & Operations Division: Paul H. Baker

Head, Garage Section: Kenley Taylor

Head, Buildings & Ground Maintenance & Repair Section: Lawrence B. Taylor

Chief Medical Officer: W. S. Ramsey

[27]

In September 1943, an administrative reorganization streamlined management, organizing the various departments into four divisions:

Community Management Division: headed by Lorne Bell and included education, internal security, welfare, the hospital, community enterprises, community analysis, community government, and evacuee property

Operations Division: headed by Roscoe Bell and included engineering, construction and maintenance, agriculture, motor transportation, and fire protection

Administrative Management Division: headed by James F. Hughes and included supply and transportation, procurement, accounting, and finance

Project Management Division: headed by Ernst and later Hoffman and included the project attorneys, the reports office, employment, leave, and relocation.

[28]

Other key staffers in Topaz's history included Russell Bankson, the second reports officer who succeeded Hull in June 1943 and E. Wafford Conrad, who succeeded Bankson in September 1944. The main community analyst at Topaz was Oscar F. Hoffman , who arrived on September 4, 1943 and served in that capacity for nearly two years. He was preceded by Weston La Barre (May 12 to June 26, 1943), whose short stint at Topaz ended with his conscription into military service. [29]

Topaz's project attorneys included

Anthony O'Brien: acting project attorney until Dec. 1942

Ralph C. Barnhart: December 1942 to September 1944

Frank Barrett: acting, September to December 1944

Mima R. Pollitt: acting, January to February 1945

Lloyd Buchanan: February 1945 to closing

[30]

Institutions/Camp Life

Community Government

As at other WRA camps, Topaz had a system of representative elected government based on blocks. Though providing inmates some voice in the governance of the camp, the various incarnations of the Community Councils had limited power in the context of what was a concentration camp and grew increasingly antagonistic towards the administration over the course of the incarceration.

There were six Community Councils (CC) along with a Temporary Community Council (TCC) over the course of Topaz's history. Each of the councils consisted of one elected representative from each residential block, a total of thirty-four. Each served a six-month term after which new elections would be held; council members could be—and often were—reelected. The Temporary Council was set up by Head of Community Services Lorne Bell as inmates began to arrive at Topaz in September of 1942. The first election was held on September 30 to elect representatives from eight occupied blocks. Elections continued in to mid-October until a full slate of representatives could be elected. Carl Hirota, a Nisei dentist from San Francisco and a JACL member, chaired the Temporary Council. Due to WRA regulations, only Nisei were allowed to hold office initially, and so the Temporary Council and first regular council were made up entirely of Nisei. Acting Project Attorney Tony O'Brien called the TCC "very active" and implied that he thought them too active, writing "I found that they had been appointing committees right and left and using them mainly for investigative purposes." The TCC was able to draft a constitution for Topaz which was ratified by a vote of inmates on December 15. [31]

The general election for the first regular council took place on December 29. Utah Governor Herbert Maw installed the first CC on January 14. San Francisco Nisei accountant Tsune Baba was elected chair. In an annual report stemming from the Reports Office, Warren Watanabe wrote that the first CC "had become almost defunct during its last few weeks since its chairman and many key councilmen had relocated." Upon Baba's resettlement in Michigan in May 1943, Masato Maruyama, a Nisei from Alameda, took over as chair. The election for the second council in June 1943 drew additional interest, since Issei were now eligible to hold office; twenty-two of the thirty-four council members were Issei, though Nisei dentist George Ochikubo was elected chair. [32]

A minor crisis roiled the second council when Ochikubo's opposition to Topaz inmates being asked to serve as strike breakers at Tule Lake led to an FBI agent interrogating him for allegedly "seditious" comments made at a council meeting. Ochikubo denied making the statement and, reasoning that someone on the council had informed on him, resigned the council on November 16. The entire council subsequently resigned. A special election on November 26 elected a new council—which was largely the same as the old one—but with a new chair, Issei Saiki Muneno. Ochikubo would return as chair of the third council installed in January 1944. The last three councils were chaired by Issei Masaru Narahara. Ochikubo later challenged the mass exclusion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast in the courts , resulting in his individual exclusion after the West Coast was opened up to Japanese Americans at the beginning of 1945. He remained active on the Topaz council until the end. [33]

Reports Officer E. W. Conrad characterized the later councils as drawing limited interest from inmates as the limits of their powers became evident. Conrad noted that Narahara and Ochikubo broke protocol at the installation of the last council in July 1945, when both explicitly criticized WRA policies in closing the camp. Historian Sandra Taylor called these later Issei dominated councils "obstructionist forces" She added that Topaz administrators "used the community councils to give the appearance of democracy" but that when the "gap between appearance and reality was… discerned by the residents,… [they] discounted the council as a result." [34]

Unrest

While there were no disturbances at Topaz on the scale of incidents at Manzanar , Poston , or Tule Lake, there were many instances in which inmates rose up to challenge aspects of their confinement, with conflict erupting between inmates and the administration and between groups of inmates. The most notable camp-wide uprising might have come in the aftermath of the most notorious incident to take place at Topaz: the fatal shooting of Issei inmate James Hatsuaki Wakasa by a watchtower sentry on April 11, 1943. The unprovoked shooting shocked and outraged the inmate population and a mass strike of inmate workers followed. Up to 3,000 inmates attended Wakasa's funeral, and inmates erected an unauthorized memorial—which was later pulled down after pressure from the War Department—at the site of the shooting. (See Densho Encyclopedia on the Wakasa shooting .)

Disputes in the workplace were the root of several disputes at Topaz. Just a few days after the arrival of the first "volunteer" group on September 11, 1942, kitchen workers charged with preparing mess halls for the mass arrival of inmates from Tanforan walked out over a conflict with their white supervisor. The strike continued for three days until an agreement was reached that limited the supervisor's authority over them, and they returned to work in time to prepare food for the first regular group of inmate arrivals on September 17. A somewhat similar dispute broke out a year later, in September 1943, among garage workers also upset about treatment by a supervisor. The subsequent walkout of garage workers spread to include agricultural workers as well and lasted a week. Topaz was plagued by corroded and leaking water and sewer pipes that required frequent repair, a difficult and dirty job. Inmate workers—many of them "loyal" transferees from Tule Lake who were stuck with the work since other jobs were taken—walked off the job in the summer of 1944 over clashes with white supervisors and a wage cut from $19 to $16 a month. Though the higher wage was restored and the overtime policy retooled, it remained difficult to find workers to repair the pipes. The Topaz hospital was also the site of much unrest among inmate workers, as described in the "Medical Facilities" section below. [35]

Tensions also broke out between inmates stemming from the "loyalty questionnaire" and segregation process. Several inmates who were viewed as pro-administration were threatened or assaulted, including artist Chiura Obata , who was attacked on April 4, 1943. Agitators threw "jars of foul-smelling material" into the barrack rooms of eight others. Eventually, Topaz administrators sent fourteen "troublemakers" to the WRA prison camp at Leupp, Arizona . [36]

Registration/Segregation/Military Service

Widespread resistance to registration emerged at Topaz, with Issei and Nisei alike questioning various aspects of the "loyalty questionnaire" and the segregated Nisei combat unit, delaying the scheduled February 10, 1943, start of registration a week. Issei objected to the wording of question 28 that asked a population that was prohibited by law from becoming U.S. citizens to "forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese Emperor"; they organized a committee of nine to ask that the question be changed and refused to register until the issue was resolved. With similar complaints coming from other camps, the WRA and army agreed to change the wording of the question. Nisei also organized a committee of 33 to demand the restoration of their civil rights before they would agree to register. But a hard-line response—included threats of prosecution for violating the Espionage Act—by both local and national WRA officials along with counter protests by professed Nisei patriots broke the Nisei protest. Registration began in earnest on February 17 and was completed by February 27. While the initial number of Nisei who volunteered for the army was low, a group of volunteers formed the Resident Council for Japanese American Civil Rights , which spearheaded a propaganda campaign that helped recruit additional volunteers. Ultimately, a slightly higher percentage of eligible men volunteered for the army from Topaz than from the WRA camps as a whole, 7.5% vs. 5.8%. [37]

In the end, a slightly lower percentage of Topaz inmates answered "yes" to question 28 (89.4%) than inmates at all of the WRA camps (91.1%). 1,459 Topaz inmates—just under 18% of the peak population of Topaz—were segregated to Tule Lake, a figure somewhat higher than the overall 13% rate. Topaz saw a slight net uptick in its inmate population when 1,558 "loyal" Tuleans arrived in September 1943, with the segregants departing for Tule Lake on the same trains that had brought the Tuleans. [38]

When Nisei eligibility for the draft was restored in early 1944, two groups formed to protest the continued segregation of Nisei in the army, the Topaz Citizens Committee and Mothers of Topaz . Though a faction of the former advocated draft resistance , the majority opted to protest segregation but not to actively resist. The latter sent a petition signed by 1,141 mothers to President Roosevelt and other national leaders objecting to the segregated Nisei military unit and to the fact that Nisei were banned from all branches of the military except the army. In the end, only seven Nisei refused to appear for their pre-induction physicals, one of the lowest figures of any of the WRA camps. [39]

Later in 1944, Nisei emissaries Ben Kuroki and Thomas Taro Higa visited Topaz to continue to drum up support for enlistment to a mixed reception. In December 1944, the first center-wide memorial service for the nine Nisei soldiers from Topaz who had been killed in action was held before a crowd of 1,300 in the auditorium. The Community Council had refused to sanction such a service previously, citing concern over how the Japanese government would view it. In the end, 451 from Topaz joined the army—80 as volunteers—and 15 were killed in action. [40]

Education

Topaz had three K–12 schools, a multi-unit pre-school program, and a substantial adult education program that included notable art and music programs. While initial plans were to build new elementary and middle/high school campuses, for the most part, regular residential block buildings ended up serving as the school campuses, a pattern that recurred at many of the WRA camps. Two elementary schools each took up half of Blocks 8 and 41 and were dubbed "Mountain View" and "Desert View" respectively. The two schools were located on opposite ends of the camp, with Mountain View serving the north and west blocks and Desert View the south and east ones. Topaz High School (THS)—which served both middle and senior high students, grades seven to twelve—took up all of Block 32. Four preschools were located in Recreation Halls 9, 13, 27, and 37. [41]

As late as a year in, the empty blocks in the middle of the camp were referred to as the future site of the high school, but the new school would never be built. Regular residential barracks served as classrooms, as well as the high school library and administrative offices. Laundry rooms were used as labs and for shop classes. The Block 32 dining hall served as the junior/senior high school auditorium and meeting space, even though its 250-person capacity was far too small for a school with over 1,000 students. Two new school buildings did later get built: an industrial arts shop opened in March 1943 and a new science building in December 1944, the latter finished just a few months before the schools closed down for good. Schools also used the new auditorium built in the central open space that was completed at the end of 1943. [42]

In part to meet Utah state requirements for a nine-month school year, Topaz School Superintendent John Carlisle and his staff rushed to open the schools by mid-October 1942. Schools opened on October 26 with an initial enrollment of 1,041 junior and senior high school students, 764 elementary, and 287 preschool. The barrack classrooms, however, proved unusable at first. In addition to the usual issues of dust, noise (due to partitions that did not go all the way to the roof), and insufficient light, the early onset of winter weather made the rooms too cold to hold classes in. After a week, schools were closed and staff and inmate volunteers were tasked with "winterizing" the barracks. Former teacher Eleanor Gerard Sekerak recalled "teetering precariously on a wobbly table, holding a sheetrock slab with both arms while hammer-wielding students banged nails on each edge—and presto, a ceiling!" Even with the fixes, school was held only during the warmer portions of the day for over a month when it wasn't canceled entirely. The installation of stoves and minimal insulation finally allowed for the resumption of full school days in early December. Furniture was sparse, and there were few if any textbooks, though conditions did slowly improve over time. [43]

As was true with other WRA camps, teacher recruitment was difficult and turnover high, though Topaz's schools did benefit from relatively stable leadership. While Carlisle left Topaz in January 1943, he was replaced by Le Grande Noble, a former superintendent of schools at Uintah County who had been the principal of Topaz High School. Noble would remain as superintendent for the duration. In his final report, Noble wrote that "[at] no time… was the teaching personnel adequate in the Topaz schools," even noting that teachers were sometimes required to teach two classes at the same time. "It is needless to point out that such a condition caused considerable unrest and discouragement in the minds of the pupils," he added. [44]

Given the difficulties of retaining white teachers, along with the relatively well-educated urban inmate population of Topaz, a relatively high percentage of teachers were Nisei. At the end of February 1943, 38 of the 48 elementary school teachers were Nisei as well as 33 of the 61 at THS. All of the preschool teachers were Nisei. Over time, many of these teachers left camp to "resettle," resulting in younger and less experienced teachers. By February 1944, two-thirds of inmate teachers had had no prior teaching experience. The combination of inexperienced teachers and increasingly demoralized students led to a deteriorating school experience by the school's last year as vandalism rose and, as historian Sandra Taylor writes, "senior boys, waiting to be drafted, were uninterested and uncooperative, and they were particularly rowdy, unruly, and disrespectful toward the Japanese American teachers who were barely older than they were." Inmate experiences were certainly mixed as some students fondly recall dedicated teachers. Others, like Bob Utsumi, recall not being challenged enough. "I wasn't prepared for the outside when I got back, in college, for college," he said in a 2008 interview. Schools shut down in June 1945 with the final commencement ceremony. [45]

As at other WRA camps, there was also an extensive adult education program at Topaz. It included the usual "Americanization" classes aimed at Issei and Kibei, geography classes aimed at would-be resettlers, craft classes, vocational classes, and English language classes. As at other camps, the adult English classes were mostly attended by women. The average monthly enrollment for the English classes was 437, of which 408 were women. Two programs somewhat unique to Topaz at least in scope were the art and music schools, which were undoubtedly functions of the urban and cosmopolitan inmate population. The art school was started by artist and University of California Professor Chiura Obata and located in Recreation Hall 7. Instructional programs included drawing, painting, sculpture, mechanical drawing, and flower arrangement, and there were Saturday classes for children. The first graduating class in March of 1943 saw certificates awarded to 350 art students. After Obata left in the spring of 1943, George Matsusaburo Hibi took over as director. Other notable artists who taught at the school included Hisako Hibi , Frank Taira , Miné Okubo , and Byron Takashi Tsuzuki . The music school was located in Recreation Hall 35 and offered piano, violin, and vocal lessons along with many other courses. Peak enrollment at the music school was 653 students. [46]

Recreation

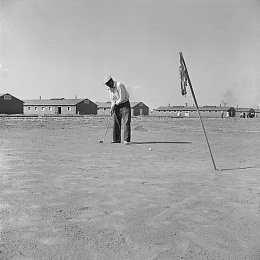

"At Topaz, the Recreation program was late in getting started," wrote Fred Hoshiyama, part of the "volunteer" group from Tanforan charged with putting together the Topaz program. Along with Tad Hirota, Bob Iki, and Kimio Obata, Hoshiyama had been part of the Tanforan Recreation Department and the quartet became the first executive committee charged with forming the recreation program at Topaz. The group brought some equipment from Tanforan, but facilities were largely lacking, as many of the block recreation halls had been assigned other uses as churches, libraries, or preschools, and there were no existing outdoor fields or courts. Empty blocks (15, 21 and central square that included Blocks 17, 18, 24, and 25) had been set aside for schools, but when residential blocks were used for the schools instead, those blocks became play areas. Along with some purchased equipment, inmates leveled playing fields and built necessary gear, including baseball backstops made out of old bed springs. By the fall of 1943, there were seventeen softball diamonds laid out, and eight leagues had fifty teams. Inmates built a dusty nine-hole golf course, twelve basketball courts, six volleyball courts, three outdoor tennis courts, and a sumo ring. Inmate workers set up playground equipment in the empty Blocks 15 and 21 that drew upwards of five hundred children a day. An ice rink was built in south of the camp in late 1942. By 1944, a larger ice rink had been built on the north side of the camp and several blocks had their own smaller rinks. [47]

Eventually, a succession of WRA staffers served as heads of community activity, overseeing the recreation program. They included Emily Minton (Oct. to Dec. 1942), James Lamb (Feb. to Dec. 1943), Eleanor Gerard (Apr. to Nov. 1944), Lawrence Horton (Dec. 1944 to Mar. 1945), and Parlell Peterson (May to Aug. 1945). [48]

There were active boys and girls scouting programs and YMCA/YWCA programs as well. The YWCA used Recreation Hall 4, while the YMCA was allocated Recreation Hall 34. The Boy Scouts claimed Recreation Hall 42 as "Scout Lodge." At Topaz, existing pre-war troops were reorganized into four Topaz troops tied to four districts of Topaz. Topaz scouts also engaged in activities with troops on the outside. A highlight for youth in these and other organizations was a trip to Antelope Springs , a camp for young people established in the summer of 1943 at a former CCC camp at the foot of Swasey Peak forty miles west of Topaz. Hundreds of youth spent weeklong visits at the camp. Closer to the barbed wire fences, inmates searched for tiny shells from old Lake Bonneville that they washed in bleach and crafted into jewelry and flowers. [49]

As at other camps, dances, talent shows and movie screenings were popular pastimes. Popular talents included singer and frequent event MC Goro Suzuki, who became a Broadway and television star after the war under the name " Jack Soo ," and the Cossacks, a singing group that would sing popular songs, while sometimes inserting their own lyrics about camp life. The Topaz Tooters, a dance band that had been the Tanforan Tooters, played dances and the high school prom. Later, as members of the group resettled, younger musicians formed the Jivesters, The Savoy Four and the Rhythm Kings. The larger Block 1 mess hall was used for large community events until the Hawai'i inmates moved there in early 1943. Later, an auditorium was built in the central plaza under the supervision of George Shimamoto. Intended as a school auditorium, it ended up being used for a wide variety of events including movie screenings. Dedicated on December 22, 1943, it had a capacity of 1,350. [50]

Both sanctioned and illicit gambling flourished for a time. Henry Hajime Endo and Hiroshi Hirashima recalled in interviews that workers who had left the camp for outside work picking sugar beets returned flush with cash and were targeted by professional gamblers in the camp who "took it all away from them in a short time." Many blocks began using bingo games as fund raisers, often for the purchase of athletic equipment or other things that would benefit the block population. But when some young people became addicted to the games, even stealing family money to play, the Community Council prohibited such games. [51]

Medical Facilities

As with many other elements of the camp, the hospital was not complete when inmates began arriving. As a result, a temporary infirmary was set up in the laundry room of Block 4, staffed by members of the first "volunteer" contingent of September 11, 1942 led by Dr. Benjamin Kondo. A week later, three more doctors and two interns arrived, though one of the doctors was soon transferred to Manzanar. A twenty-eight-bed adult ward opened in the new hospital complex on Sept. 26, 1942 and a dedication ceremony was held on October 18. The complex was located on the north border of the camp just west of the MP area and came to include seventeen buildings, including wards for adults and children; an isolation ward; an obstetrical ward, x-ray, medical laboratory, surgery and public health departments; pharmacy, dental, and optometry clinics; and doctors' and nurses' quarters. There were eventually 128 beds in total. Severe shortages of supplies and equipment dogged medical personnel for the first few months, and staffing shortages recurred throughout the life of the hospital. In particular, nurses and nurse aides were perpetually in short supply given the many better opportunities in outside hospitals. Aides in the isolation/TB ward were particularly difficult to find given Japanese cultural taboos regarding TB. By mid-1944, the medical staff was asking friends and family of patients in the isolation ward to volunteer. [52]

Throughout its history, the hospital was riddled with strife both between inmates and between inmate and white staff, fueled by prewar rivalries and professional jealousies and the artificial pay and status gap between white and inmate staff that often saw less qualified white doctors supervising more qualified inmate doctors while being paid twenty times the maximum allowed WRA salary of $19 a month. There were three incidents that reached a crisis status. The first stemmed from an apparent professional rivalry between inmate doctors. When two doctors left Topaz in late 1942, the medical staff petitioned the WRA to bring in another doctor to help lessen their workloads. The Nisei surgeon transferred over from Manzanar proved to be a rival to the existing Issei surgeon from Sacramento, the latter of whom mobilized the other doctors and Issei leaders to threaten to quit if the Nisei was brought to Topaz. When he was brought to Topaz and assigned to the hospital, the other doctors did tender resignations, though a Community Council committee managed to convince them to stay on. The Issei surgeon eventually resigned. Later, in July 1944, a mass strike was averted when administrators fired striking ambulance drivers; the unrest was due to dissatisfaction with WRA policies that resulted in cutbacks in the ranks of inmate dentists, pharmacists, and optometrists. Later in 1944, the deaths of two babies and other objections led the Community Council to demand the ouster of the white chief medical officer. Luther Hoffman, the second camp director, while acknowledging that this man "had handled his relations with the evacuee community rather badly at times," refused to accede to the council's demand, but did reach a compromise with the council that allowed the chief medical officer to stay on. [53]

In the end, there were 3,973 hospital admissions over the life of the camp, an average of 110 per month. Outpatient visits averaged 1,886 per month. Inmate dentists handled an average of 1,365 visits a month and optometrists saw an average of 638 patients per month. The medical complex began to close down in mid 1945; the last twenty-one patients transferred to outside facilities just prior to the camp's closing. [54]

Newspaper

The main newspaper at Topaz was the Topaz Times , which officially debuted with the October 27, 1942 issue and ended with the March 30, 1945 issue. As at other camps, the camp newspaper was staffed by inmates who operated the paper under the supervision of the WRA Reports Office staff. In addition to the Times , the Topaz Reports Office oversaw several different publications including separate newspapers/newsletters that pre- and post-dated the Times , and Trek , perhaps the most accomplished literary and arts journal produced in any of the WRA camps. [55]

The first publication at Topaz was the Information Bulletin , published under the supervision of the first reports officer, Irwin Hull and distributed to the first "volunteer" group to arrive at Topaz from Tanforan on September 11, 1942. Hull hired Henri Takahashi as the proposed editor of the newspaper on September 14, and the first "pre-issue" of the Topaz Times appeared on September 17, in time for distribution to the first group of regular arrivals from Tanforan. Nine more pre-issues followed, the last one dated October 24. The pre-issues focused on topics of interest to the new inmates arriving at Topaz such as housing, construction of facilities, and job opportunities. The first official issue of the Times appeared on October 27. It was published daily on Tuesdays through Saturdays and was generally four to six pages in length. A Japanese language supplement appeared by the second issue and would become a regular feature. Initially consisting just of translations of English language articles, the Japanese section later published unique content, including a page of Japanese poetry. Beyond the usual content of WRA camp newspapers, the Times included a good amount of news regarding the San Francisco Bay Area, given that its unusually homogeneous population almost all came from that area. [56]

The frequency of publication declined over time, going to three times a week in March 1943, then to two issues a week in October 1944, as the inmate population shrank and key editorial staff members left the camp. Early issues were mimeographed at Hinckley High School, but mimeograph machines were soon acquired that allowed for in-camp production. The Times had a peak circulation of 3,500 in 1943. Copies were distributed within the camp (through block managers) for no charge. Inmates who had resettled could continue to receive the paper by paying for postage. After the Times ceased publication, it was replaced by the Relocation News , which focused on encouraging inmates to leave. The News began in April 1945 and continued through October. Since many of the remaining inmates were Issei, half of the paper was in Japanese. [57]

As with other papers, the Times walked a fine line regarding content with camp administrators. After an October 1942 visit to the camp, WRA Reports Officer John Baker noted that Topaz Director Charles Ernst didn't want the Times to print news about things in other camps that Topaz did not have; he thus required that he approve any news published about other camps in the Times . Baker wrote that this reflects a "lack of confidence in staff of the paper, probably some mistrust of the press in general," decrying what he saw as "rather strict censorship." Later, during the registration crisis, Reports Officer Russell Bankson fired two staffers of the Japanese section when he found out that they were calling for resistance to registration in the Times . Later, when reporting on the Wakasa killing, the Times account falsely reported that Wakasa had been shot while trying to climb through the fence. This was never corrected. [58]

Three issues of Trek appeared between December 1942 and June 1943. It included contributions by such notable Nisei writers as Toyo Suyemoto , Toshio Mori , and Larry Tajiri . Art Editor Miné Okubo was responsible for its striking covers. 3,750 copies of the Trek were distributed. A similar publication, All Aboard , appeared in the spring of 1944. [59]

Store/Co-op

Topaz had an extensive network of retail stores and service businesses that operated in a cooperative format, with an inmate board of directors, an inmate membership, and profits that went back to the co-op. Led by Community Enterprises Chief Walter W. Honderich, the first camp store was open by September 12 to serve the first group of "volunteers" who had arrived the day before. That stores included only "fast-moving merchandise such as candy, ice cream, fruit juice tobacco, soap, and miscellaneous drug items." Led by Rev. Taro Goto and Hiroshi Korematsu, who had pushed for a co-op out of dissatisfaction with the stores at Tanforan, co-op proponents managed to put together a Cooperative Congress that included two representatives from each block. At their first meeting on October 7, they elected a fifteen-member board of directors and later decided on a $1 membership fee for all interested inmates over sixteen. The new co-op took over management of the stores as of October 14, 1942. The board appointed a committee to draw up bylaws and a charter, which were approved on February 1, 1943. [60]

The scope of co-op stores and services grew quickly. Membership reached 5,170 and grossed $20,000 a month by the end of 1942. By the fall of 1943, there was a shoe repair shop, radio repair shop, dry cleaners, hand laundry, bank, and mail order office in the Block 26 recreation hall; a general canteen with a newsstand and soda fountain that sold groceries, tobacco, hardware, and other items in the Block 19 recreation hall; dry goods, clothing, and shoe stores in the Block 12 recreation hall; and barber shops in the laundry rooms of Blocks 8 and 41. [61]

Over the course of the co-op's history, a number of issues and disputes emerged. The early board of directors consisted largely of former retail business owners who insisted on running the business themselves. Their conservative ordering strategy even as merchandise sold quickly led to shortages of many items. Toyo Suyemoto recalled long lines for rare goods and managing to get one of only seven available pairs of pinking shears by being tipped off by her deliveryman brother. There was later discord among co-op board members over whether to reimburse members their membership fee and on a decision to start a credit union despite already having a bank. [62]

Industry

Industry in Topaz was relatively limited compared to other WRA camps and ultimately developed just to serve the inmate population. WRA administrators considered a factory that would build camouflage nets for use by the army—such plants were formed at Manzanar, Gila River, and Poston to various degrees of success—but decided not to go forward because of the issue of how to navigate the WRA pay scale in such a factory. For similar reasons, ventures that would have built cartridge belts, tents, and optical lenses also did not come to fruition. [63]

The most impactful industrial endeavors were a furniture factory that produced furniture for the camp and bean sprout and tofu factories that produced those items for consumption in camp mess halls. The modest bean sprout project started in a laundry room, but later expanded into a 20 x 20 recycled CCC building in Block 15. An inmate crew of three was able to produce enough sprouts to feed the camp—over 6,000 pounds worth in August 1944 for instance—at a cost of 3¢ a pound. [64]

Though the idea of a tofu factory was discussed for many months, it did not become a reality until the spring of 1944. Another recycled CCC building was used and equipped with a purchased grinder and a steam boiler "borrowed" from the hospital. All other equipment was made by inmates at the camp. A crew of nine was able to produce tofu cakes for the camp at 3¢ per cake versus an outside cost of 20 to 25¢ each. Production reached 27,936 pounds by March 1945, after which production ramped down as the camp prepared to close. The plant also produced soy bean milk that was used to make sherbet for mess hall consumption. [65]

Agriculture

Agricultural operations at Topaz were relatively limited both because of environmental conditions including poor soil quality and a short growing season and because of the lack of experienced farm labor. There were few farm laborers among the almost entirely urban, San Francisco Bay Area population in Topaz and fewer than 250 who were farmers prior to the war. Transportation of laborers was also an issue, as the farming areas were three to six miles away from the residential areas, far enough that camp administrators required that inmate workers be accompanied by white escorts. As a result, Topaz had the smallest agricultural program of any of the WRA camps both in terms of acreage and of vegetable production. Inmates nonetheless produced meat and vegetables that contributed to dietary needs of the camp population. [66]

The farming operation included livestock, feed crops, and truck crops. The livestock operation included poultry, hogs, and beef and was probably the most successful of the agricultural programs. In 1943 and 1944, the farm produced 1,210 turkeys and 16,432 pounds of meat; 9,200 chickens and 26,462 pounds of meat; 1,460 cattle and 689,898 pounds of beef; 2,983 hogs and 494,172 pounds of pork; along with just under 83,000 dozen eggs. Enough beef and pork was produced to supply all of the camp's needs (once delivery started in mid-1943), and there were enough cattle to send 290 head to Minidoka. The agricultural program also grew nine feed crops to support the livestock, though it produced only a third of the required feed. [67]

Twenty-six different kinds of vegetables and fruits were produced at Topaz, with onions, daikon, cantaloupe, spinach, and Swiss chard being produced in the largest quantities. While local production met most of the camp's needs in season, Topaz was a net importer of produce, with crops from Tule Lake and Gila being brought in. A late frost on June 4, 1943 and early one on Sept. 16, 1944 also killed many crops. [68]

Religion

Topaz had active Protestant, Buddhist, Catholic, and Seventh-Day Adventist congregations that seemingly cooperated to an unusual degree. Meeting initially in various block recreation halls, dedicated Protestant and Buddhist church buildings were constructed—largely by inmates—in the central plaza out of recycled former CCC buildings in 1944. At its peak, a claimed 5,000 attended regular church services at Topaz, over 60% of the peak population of the camp. [69]

There were roughly equal numbers of Protestants and Buddhists at Topaz, and they cooperated to start an Inter-Faith Council. Rev. Taro Goto, the former pastor of the Pine Methodist Church in San Francisco was elected chair, and the group held a number of programs in 1943 and aided with resettlement subsequently. There was an early joint Buddhist/Protestant service on September 13, 1942 that JERS fieldworker Fred Hoshiyama was surprised by, observing that "[i]n normal pre-war community life, such a thing would never be possible." [70]

The Protestants also met together as one group, forming an ecumenical church led by Goto and Rev. Lester Suzuki, the former pastor of the Berkeley Methodist United Church. The Protestant Church of Topaz brought together thirteen Bay Area churches and held a formal opening on November 8, 1942. JERS fieldworker Doris Hayashi observed that of the 300 who attended the opening, most were Issei, and the ceremony was conducted mostly in Japanese. As of September 1943, Protestants met in the recreation halls of Blocks 5, 22, 27 and 33, along with the dining hall of Block 32 and numbered about 1,870. The Buddhists met in the recreation halls of Blocks 8 and 28 and numbered 2,400. Catholics and Seventh-Day Adventists met in the recreation hall of Block 14 and had a weekly attendance of 200 and 500 respectively. [71]

In January of 1944 two former CCC buildings, each 20 x 100, were brought into the camp's central plaza on opposite sides of the auditorium to be turned into church buildings. Buddhist church construction began on January 13; 101 men completed the renovations on April 17. Protestant church construction began on January 25; 96 men completed the work on April 8. A joint dedication ceremony was held on April 18 attended by 400. [72]

Topaz also became the center of Buddhist Mission of North America, the national organization of the dominant Nishi Hongwanji sect which had had its headquarters in San Francisco prior to the war. Since Nishi Hongwanji Bishop Ryōtai Matsukage was not interned like most other Buddhist priests, the BMNA headquarters went with him to Topaz when he was incarcerated along with the rest of the San Francisco Japanese American community. At Topaz, Matsukage issued a statement pledging loyalty to the U.S. Nisei Rev. Kenryō Kumata organized a national Buddhist conference in Salt Lake City attended by inmates from other camps; at this event the name of the national organization was changed to the more American sounding "Buddhist Churches of America." Topaz was also the site of a three-day Buddhist gathering in late April 1944 attended by forty representatives from both outside communities and other WRA camps. [73]

Library

Topaz had five libraries: the main Topaz Public Library (TPL), a library for Japanese language material, and libraries at the high school and each of the two elementary schools. The first two were managed by the Community Services/Community Management Division, while the latter three came under the Education Section. [74]

The TPL began as essentially a continuation of the library at the Tanforan Assembly Center, with books from that library being shipped to Topaz and two former library workers from there, Ida Shimanouchi and Alice Watanabe, taking the lead in setting up the new library. Work began on the library in Recreation Hall 32 on October 2, 1942. The space was unfinished and unheated, leading to days when work had to be canceled due to the cold. Inmates contributed books and magazines to the Tanforan collection, and the library was able to open to the public with a collection of nearly 7,000 books on December 1. The TPL soon moved to the Block 16 recreation hall. [75]

The Block 16 space was essentially an entire unpartitioned recreation hall with mess hall tables and benches running down the middle and inmate-built shelves lining the walls. Half of the space was devoted to adult books and half to children's books. Small rooms on either end were used by the book binder and as an office for the staff. The staff staggered hours to keep the library open on evenings and weekends and made regular visits to the Delta Public Library whose staff offered helpful advice. The collection grew to include fifty-two periodicals, including major national newspapers as well the Oakland Tribune and San Francisco Chronicle . One unique innovation was a rental collection of new books that rented for 5¢ a week. In January 1943, the TPL was able to rotate in some books from the Salt Lake County Library at Midvale and also initiated an interlibrary loan service with college libraries in Utah and the University of California at Berkeley. By the end of March 1943, the collection had grown to over 8,500 books and patronage peaked at nearly 500 a day. It became a popular place for young people to gather to socialize and do homework. Motomu Akashi recalled spending many hours in the library, since "[i]t was much more comfortable than our apartment, especially during the winter." He called the library "my salvation" that "brought me just that small pleasure needed to overcome my depression." [76]

To serve the Issei and Kibei population, a Japanese language collection was formed out of donations from inmates. Opening as a part of the regular TPL in February 1943, the Japanese section became so popular that it moved to its own space in Recreation Hall 40 in May, later moving to Recreation Hall 31 in February 1944. The collection began with about 1,000 books and eventually grew to 5,000, with daily attendance of three hundred. The inmates from Hawai'i became frequent users of the library and put on a popular exhibition of craft items in Hawai'i. Later, the Japanese library hosted exhibitions of artists from the art school. The high school library was in a dedicated barrack in Block 32 and had a capacity of one hundred students. While the public libraries were staffed entirely by inmates, the high school library was supervised by white librarians on the WRA payroll. [77]

As more Nisei began to resettle, the staff at the TPL turned over quickly and hours were cut. It closed on June 23, 1945, with remaining books being combined with the school collections. [78]

Closing

As 1945 dawned, there were still 5,922 inmates at Topaz, about 73% of the peak population. As at other WRA camps, the remaining inmates—a large portion of whom were either elderly Issei or families with young children—reacted in different ways to announced plans to close the camp by the end of 1945, with some resigned to making plans to leave and others taking a hard core "stand pat" stance. Inmates discussed these and other issues at the All Center Conference held in Salt Lake City in February 1945, which Topaz inmates, led by Community Council Chairman Masaru Narahara, took the lead in organizing. But as closing time approached, opposition to leaving ebbed as inmates, many without a place to return to, realized the inevitability of the camp's demise. [79]

In mid-August, there were still 4,000 people left. All were moved out of Topaz one way or another by the scheduled closing date of October 31. Project Director Luther Hoffman locked the gates behind the last bus to leave at a 1 pm ceremony attended by the staff. The last group to leave were thirty-two from Hawai'i, who had to stay on until shipping arrangements could be made. In the end, about 44% of Topaz inmates initially returned to the West Coast, nearly all of them to California. [80]

Timeline

September 11, 1942

The first "volunteer" contingent of 214 people arrives from Tanforan to prepare the camp for occupation.

September 17, 1942

The first regular continent from Tanforan arrives. About 500 a day would arrive for the next seven days.

September 27, 1942

Representatives from outside sugar beet growers come to Topaz to recruit workers. Eleven are on payrolls by September 30.

September 30, 1942

Elections held for Temporary Community Council.

Oct. 7, 1942

First Cooperative Congress held; 27 out of 32 blocks are represented and a charter is drafted.

October 18, 1942

The hospital is dedicated.

October 19, 1942

Elementary schools begin instruction in Blocks 8 and 41; 677 students registered.

October 27, 1942

The first regular edition of the

Topaz Times

is published.

December 1, 1942

Formal opening of the Topaz Library

December 1, 1942

Arrival of U.S. Army team to recruit Nisei for the Military Intelligence Service. Nine men volunteer from Topaz and leave for Camp Savage on December 7.

December 9, 1942

Grand opening of the dry goods store.

December 20, 1942

Kozo Fukugai, 32, becomes separated from his hiking party to Mt. Topaz. A massive search that comes to involve 1,000 Topaz inmates ensues. Fukugai is found alive 72 hours later some ten miles west of Topaz. Mt.

December 23, 1942

General election for the permanent community council held.

January 14, 1943

Utah Governor Herbert B. Maw visits Topaz to swear in the new community council.

February 27, 1943

Registration is completed.

March 14, 1943

226 Japanese Americans from Hawaii arrive at Topaz and are situated in Block 1. The group included 176 men with the rest family units.

April 11, 1943

The shooting of James Hatsuaki Wakasa.

September 4, 1943

Garage workers—soon joined by agricultural workers—begin a week-long strike over mistreatment by supervisors.

September 18, 1943

The first train containing 441 "loyals" from Tule Lake arrives at Topaz. 489 "disloyals" from Topaz go to Tule Lake on the same train the next day. Two subsequent trains—on September 23–24 and 28–29—transfer similar numbers of inmates between Tule Lake and Topaz as part of the segregation process.

December 22, 1943

Dedication of Topaz Civic Auditorium.

December 1943–January 1944

A flu epidemic—perhaps the largest outbreak in any WRA camp—results in some 1,400 cases. Block 9 along saw 113 cases, nearly half the block's population.

Feb. 20, 1944

A ceremony is held to acknowledge the receipt of "comfort" goods sent by the Japanese Red Cross. The goods include soy sauce, miso, tea, and other items. About 1,000 attend the ceremony.

March 1, 1944

The first group of twenty-five draftees from Topaz report for pre-induction physicals at Fort Douglas, Utah. (8)

March 1944

Tofu factory opens.

April 18, 1944

Joint dedication of Protestant and Buddhist Church buildings in central plaza.

April 1944

At a three-day meeting at Topaz attended by 40 representatives from both the free zones and WRA camps, the Buddhist Churches of America is officially formed as a Nisei run organization.

May 19, 1944

War hero Ben Kuroki arrives at Topaz for a four-day visit.

June 16, 1944

Welcome reception held for new project director L. T. Hoffman.

July 3–4, 1944

Visit and speeches by PFC Thomas Taro Higa.

December 3, 1944

The first camp wide memorial service held for Topaz Nisei killed in action held in auditorium before capacity crowd of 1,300.

December 18, 1944

The U.S. Supreme Court rules on a case instigated by Topaz inmate

Mitsuye Endo

challenging the continued incarceration of Japanese Americans. The Ex Parte Endo decision led to the opening of the restricted West Coast area to Japanese Americans and to the closing of the concentration camps.

June 1, 1945

The closing of Topaz's schools.

July 12, 1945

Closing date of November 1 announced.

August 29, 1945

Population of the camp is 3,400 two months prior to the announced closing date of November 1.

October 31, 1945

The official closing day of Topaz

Quotes

"Ye Gods, it's a terrible place here. The dust storms are awful—can't see ahead of you, the rooms are dusty and even closed windows can't keep out the dust. We eat, sleep and live in the dust. Golly, how I miss California. I thought our stables in Tanforan were bad but it'd be heaven if we could only go back. People about me are discouraged and disappointed--they say it's no place for humans to live."

Riyoko Kushida, 1942

[81]

"The gray, uniform barracks which house the evacuees were not completed when the first batch arrived—they were not completed when the last batch arrived—and now after nearly two months, they are still not completed. Most of them had neither ceilings nor Inside walls—with the result that people had to sleep with their faces covered by towels to protect themselves from swirling dust."

Maxim Shapiro, 1942

[82]

"Topaz was a quiet center. Even its social activities moved along at a leisurely pace. There had been no serious outbreaks of trouble, no apparent resentment at the regimented life forced upon the residents. Of course it was but natural for them to feel bitterness and anger at the evacuation that had taken them from their homes and confined them in a relocation center, but these emotions as yet lay dormant."

Warren Watanabe, 1943

[83]

""I am weary of camp, the desert, the dust and the heat!!!! Words of faith and hope I cannot sincerely find in my heart… And yet, we alone of the world are not suffering…. We are but a few of the millions…. We must wait with patience and faith…. Wait with the world, with hope and with a prayer for a lasting peace; a just and eternal peace, which must come, and come soon……"

Yoshiko Uchida, 1942

[84]