Toshio Mori

| Name | Toshio Mori |

|---|---|

| Born | March 3 1910 |

| Died | 1980 |

| Birth Location | Oakland, CA |

| Generational Identifier |

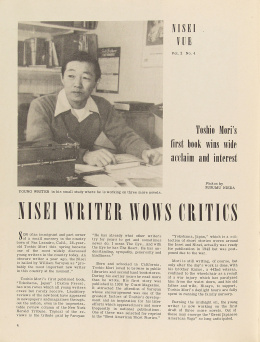

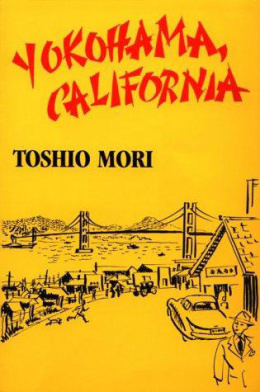

Northern California Nisei writer Toshio Mori (1910–80) was the first Japanese American to publish a book of short stories in the United States. Originally scheduled to debut in 1942, his collection Yokohama, California was delayed by World War II, and eventually published in 1949 to brief acclaim. At the U.S. government incarceration camp Topaz , Mori worked for the camp newspaper and continued to write fiction. Although he remained committed to his craft the rest of his life, widespread recognition within the Japanese American community did not arrive until the 1970s, when a more receptive generation of Sansei readers, writers and critics rediscovered his work. Mori's compassionate, quirky portraits based on the Issei and Nisei characters he observed around him, and his sensitive portrayals of intergenerational tensions captured the pathos, humor, dreams and insecurities of Japanese American life both before and after World War II.

Before the War

Toshio Mori was born on March 3, 1910, in Oakland, California, the third of four sons of Issei Yoshi and Hidekichi Mori of Hiroshima prefecture. His family ran a bathhouse for local Japanese then operated a nursery, relocating to the rural town of San Leandro in 1915. From second grade on, Mori made the twelve-mile commute to Oakland by himself, and when he was nine, began helping in the family business. As a youth he dreamed of becoming a baseball player, an artist or a Buddhist missionary, interests that gave way to an absorption in the popular dime novels of the period. As Mori became increasingly interested in fiction, he read O. Henry, Stephen Crane, Sherwood Anderson, de Maupassant, Balzac, Chekhov, Gorky, and Gogol, and began writing his own stories. According to a self-imposed schedule, he wrote from 10 p.m. to 2 a.m. nightly, after working long hours in the family business. [1]

Even though Mori's intended audience was the wider, white American public, his subject matter was the close-knit Japanese American community he lived in. Although he once noted that he received enough rejection letters to paper a room, he told interviewer Russell Leong, "When I started to receive so many rejections a day....rejections didn't mean much to me after that." [2]

Mori acknowledged that his Japanese-speaking upbringing hampered his English-language abilities ("My language was awkward and, as a whole, I believe I was a typical Nisei without high education"), so to augment his vocabulary, tried to memorize the 40,000 words in his first abridged dictionary. [3] Yet his immersion in the spoken language of the Nisei, and his grasp of the cultural longing and loneliness of his people as well as their strong sense of obligation and community gave his stories a verisimilitude inaccessible to writers who observed his world from without. Little by little, he began to receive encouraging letters from large magazines, and contributed to the prewar San Francisco-based Nisei publication Current Life, as well as The Coast, Common Ground, Pacific Citizen , New Directions , The Clipper , The Writer's Forum , and Matrix . [4]

Mori's prewar stories serve as a valuable window into that forgotten era before the major trauma of Japanese American history, the unconstitutional forced evacuation and incarceration of World War II. Many of his tales from this period evoke an idyllic, hopeful period, emitting what poet and critic Lawson Fusao Inada called "a burnished glow which simply reflects the actual atmosphere of the time, the way the people felt, saw and lived." [5] Yet signs of the growing tension between the United States and Japan leading up to World War II, and the related rise in racial tensions along the West Coast of the United States, are visible in stories such as The Brothers , an allegorical tale about two young Nisei brothers who wage battle over a desk given to them by their father. [6]

Wartime Years

Relocated in 1942 from San Leandro to the Tanforan temporary prison camp in San Bruno, California, and then to Topaz U.S. government prison camp in Utah, Mori joined the staff of the concentration camp newspaper, Topaz Times and was named "camp historian." [7] He also published stories in Trek , the camp magazine. He later spoke of his fascination with camp life because of the large concentrations of Japanese Americans in each, recalling, "I used to think there were eight thousand stories to be told." [8] The tension between an Issei generation that remained loyal to Japan despite its mother country's increasingly aggressive stance on the world stage and a Nisei generation that longed for acceptance in American society became the basis for some of Mori's stories, including his short novel "The Brothers Murata." A tale of two brothers imprisoned at Topaz who fall out over the question of patriotic duty to country, the novel is dedicated to Mori's younger brother Kazuo, who was seriously wounded in battle as a sergeant in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team , and to Mori's parents and the rest of his family.

Yokohama, California

Slated for publication in 1942, Mori's first and best-known book was delayed with the outbreak of war and finally published by Caxton Printers Ltd. in 1949. Most of the short stories in the collection were written in the late 1930s and early 1940s, though some were set even earlier. His prewar stories (inspired by Sherwood Anderson's 1919 short story collection Winesburg, Ohio , which probed the lives of a small town's residents) take a generally optimistic view of the human comedy he watched unfold in the Japanese American community. In 1949, to his tales of dreamers, philosophers, hard workers, cheats and saintly mothers, Mori added two, darker, autobiographically based stories. In "Tomorrow is Coming, Children," written while Mori was imprisoned at Topaz, an elderly Issei grandmother recounts her life story to her grandchildren, her rough passage by boat, racist attacks on her home, and now enduring the pain of witnessing her native land at war with her adopted country. In "Slant-Eyed American" Mori plumbed the contradictions and painful emotions that remain unspoken during the reunion of Nisei soldier on furlough with his family during the immediate aftermath of Pearl Harbor.

Critical Reception

In his introduction to the 1985 re-publication of Yokohama, California , poet Lawson Fusao Inada called it "the first real Japanese-American book," and linked Mori's tales to the " shibai tradition of folk drama and humorous skits," many of which "are the very source of wisdom and depth." [9] He also examined the backhanded compliments contained in writer William Saroyan's introduction to the collection, which began, "Of the thousands of unpublished writers in America there are probably no more than three who cannot write better English than Toshio Mori. His stories are full of grammatical errors," before praising Mori as "one of the most important new writers in the country at the moment," a "natural-born writer." To Inada, the fact that Mori grew up in a bilingual household "represented more access , than handicap," allowing him to render the nuances of spoken Japanese in "plain and regular English." But Inada lamented the fact that even though Mori "saw his people as the stuff of great art," "his own people ignored, rejected the art that he produced."

Postwar Years

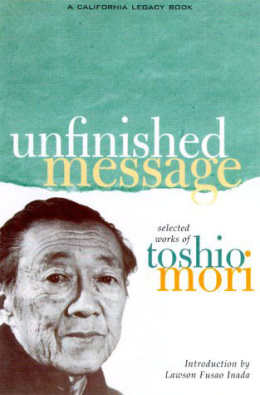

Mori married Hisayo Yoshiwara in 1947 and the couple had one son, Steven. By 1949 Mori had returned to Oakland to live. His first novel, Woman from Hiroshima , was published in 1978, and a year later his second collection of short stories, The Chauvinist and Other Stories debuted. His stories have also been published in numerous anthologies. In his foreword to Unfinished Message: Selected Works of Toshio Mori (2000) Mori's son Steven Y. Mori described an "always upbeat," devoted father who ran a nursery then worked as a salesman for a wholesale florist by day, and wrote by night. He was a man, his son wrote, who was "far more complex than people realize," writing stories about other cultures, even trying his hand at greeting card writing and song lyrics. With the renewed public attention of the 1970s Toshio Mori began speaking at college campuses and developed friendships with young Asian American writers. [10] After suffering from ill health for two years, Mori died in 1980 of a heart attack.

For More Information

Barnhart, Sarah Catlin. "Toshio Mori: (1910–1980)." In Asian American Novelists: A Bio-Bibliographical Critical Sourcebook , edited by Emmanuel S. Nelson. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000.

Horikoshi, Peter. "Interview with Toshio Mori." In Counterpoint: Perspectives on Asian America , edited by Emma Gee, et al. Los Angeles: Asian American Studies Center, University of California, 1976.

Lee, Rachel. "'The Brothers,' by Toshio Mori." In A Resource Guide to Asian American Literature , edited by Sau-ling Cynthia Wong and Stephen H Sumida. New York: Modern Language Association of America, 2001.

Mori, Toshio. The Chauvinist and Other Stories . Los Angeles: Asian American Studies Center, University of California, 1979.

———. Yokohama, California . 1949. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1985.

———. Unfinished Message: Selected Works of Toshio Mori . Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2000.

Footnotes

- ↑ Russell Leong, "An Interview with Toshio Mori," in Unfinished Message: Selected Works of Toshio Mori (Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2000), 215–224.

- ↑ Leong, "An Interview With Toshio Mori," 228.

- ↑ Ibid., 229.

- ↑ Toshio Mori, Yokohama, California (1949. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1985), acknowledgements.

- ↑ Lawson Fusao Inada, "Introduction," Yokohama, California , (1949. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1985), ix.

- ↑ Rachel Lee, "'The Brothers,' by Toshio Mori," in A Resource Guide to Asian American Literature , eds. Sau-ling Cynthia Wong and Stephen H. Sumida (New York: Modern Language Association of America, 2001), 256-258.

- ↑ Sarah Catlin Barnhart, "Toshio Mori: (1910–1980)," in Asian American Novelists: A Bio-Bibliographical Critical Sourcebook , ed. Emmanuel S. Nelson (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000), 234.

- ↑ Leong, "An Interview With Toshio Mori," 236.

- ↑ Inada, "Introduction," v-vi.

- ↑ Steven Y. Mori, "Foreword," Unfinished Message: Selected Works of Toshio Mori (Berkeley: Heyday Books, 2000), ix-x.

Last updated Oct. 17, 2021, 2:54 p.m..

Media

Media