John DeWitt

| Name | John L. DeWitt |

|---|---|

| Born | January 9 1880 |

| Died | June 20 1962 |

| Birth Location | Fort Sidney, NE |

Wartime commanding general of the Western Defense Command and the Fourth Army. As head of the Western Defense Command, John L. DeWitt (1880–1962) has often been cast as one the primary villains in the drama leading up to the mass forced removal and detention of Japanese Americans from the West Coast.

Career to World War II

John Lesesne DeWitt was born at Fort Sidney, Nebraska, to a military family and raised at various army posts. His father, Calvin DeWitt, was a former Civil War infantry captain and a Princeton graduate, and his brothers Calvin, Jr. and Wallace were also generals. He left Princeton in 1898 to enlist in the Spanish-American War and followed it with the first of four tours of duty in the Philippines in 1899. He became a supply officer and rose up the ranks, working in the office of the quartermaster general in Washington from 1914–17 and as assistant chief of staff for the army's War Plans Division in the early 1920s. He became quartermaster general in 1930 and was granted command of the Fourth Army and Western Defense Command in 1939 at the age of 59.

His pre-World War II career holds a couple of clues as to the source of his apparent enmity towards ethnic Japanese. While with the War Plans Division, he led a team in the creation of a "Joint Defense Plan" for Hawai'i in the event of war with Japan that called for the institution of martial law and the selective detention of Japanese enemy aliens. A variation of this basic plan was in fact carried out in Hawai'i in contrast to the action DeWitt led against Japanese Americans on the West Coast. His four tours of duty in the Philippines no doubt shaped his views of Japanese as well, particularly his 1904–05 tour during and after Japan's victory in the Sino-Japanese War and in 1935–37 during the Japanese war with China.

The Road to Executive Order 9066

Over the two-and-a-half months between the attack on Pearl Harbor and the issuing of Executive Order 9066 , DeWitt, made a range of conflicting pronouncements and proposals regarding the issue of Japanese Americans on the West Coast that seem to reflect some level of panic and confusion mixed with a strong self-preservation instinct. As historian Roger Daniels writes, "no one who read the transcripts of De Witt's telephone conversations with Washington or examines his staff correspondence can avoid the conclusion that his was a headquarters at which confusion rather than calm reigned, and that the confusion was greatest at the very top." [1]

Amid fears of further Japanese attacks and unsubstantiated reports of signaling of Japanese submarines from the coast—along with the news that the army and navy commanders in Hawai'i had been relived of their duties—DeWitt's first proposal regarding enemy aliens on December 19 advocated the removal of "all alien subjects fourteen years of age and over." [2] But a week later, he resisted the entreaties of army provost marshal general and longtime friend Allen Gullion for arresting all West Coast Japanese Americans. "...we are going to have an awful job on our hands and are very liable to alienate the local Japanese," he told Gullion. "An American citizen, after all, is an American citizen." [3]

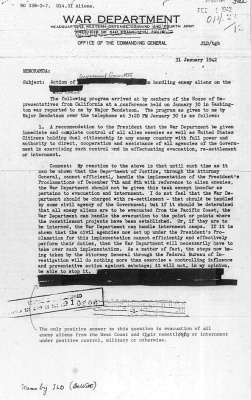

The arrival of Gullion's young assistant Karl Bendetsen in San Francisco to assist DeWitt was a turning point. At a January 4 meeting that included Justice Department officials, the idea of establishing Category A zones around sensitive areas was hatched, where everyone could be excluded, with some given passes to be allowed back. At that meeting, he stated, "I have little confidence that the enemy aliens are law-abiding or loyal.... Particularly the Japanese. I have no confidence in their loyalty whatsoever. I am speaking now of the native born Japanese." [4] The idea that even Nisei were now irredeemably "Japanese" would remain consistent for him henceforth.

On January 21, DeWitt produced a list of 86 such zones from which all enemy aliens would be removed, a total of 7,000 of which 40% were Japanese. But over the next week, the continuing pressure for mass removal of all West Coast Japanese Americans by Gullion and Bendetsen, the release of the Roberts Commission Report on January 25, and the alarming rise in public calls for mass removal reinforced by meetings with California governor Culbert Olson and attorney general Earl Warren pushed DeWitt to toughen his stance. By the end of January, he had agreed that Japanese American citizens as well as immigrants would be moved out.

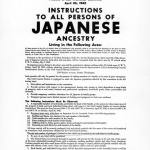

But in early February, he had yet another plan. After a conference with Governor Olson and Tom C. Clark , the coordinator of the Alien Enemy Control Program in the Western Defense Command, DeWitt advocated a plan to have Japanese American men work as volunteer laborers on "resettlement projects" within California. Informed of this, Gullion went directly to Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy and convinced him of the necessity of mass removal. McCloy in turn obtained the approval of Secretary of War Henry Stimson and of the president on February 11, sealing the fate of Japanese Americans. Executive Order 9066 was issued on February 19.

DeWitt appointed Bendetsen to head the newly formed Civil Affairs Division and the Wartime Civil Control Administration on March 12, putting him charge of the logistics of removing 110,000 people from their homes and communities. For the rest of his tenure, DeWitt continued to take positions that reinforced his original contention that Japanese Americans could not be trusted and that their loyalty could not be determined, opposing allowing Nisei into the army as combat troops and opposing Japanese American resettlement on the West Coast. As plans for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team crystalized in early 1943, DeWitt told Gullion "[t]here isn't such a thing as a loyal Japanese and it is just impossible to determine their loyalty by investigation—it just can't be done." [5] In front of a House Committee on April 15, 1943, he stated: "There is a feeling developing, I think, in certain sections of the country, that the Japanese should be allowed to return. I am opposing it with every proper means at my disposal." [6] This general contention was reflected in his Final Report, Japanese Evacuation From the West Coast, 1942 , first issued in April of 1943. McCloy's objection to DeWitt's claim that it was "impossible" to determine the loyalty of Japanese Americans led to the report's being rewritten to edit that passage.

Leaving the Western Defense Command and Postwar Life

At an off the record news conference on April 16, 1943, DeWitt uttered his infamous "A Jap is a Jap" statement in reiterating his opposition to allowing Nisei soldiers on the West Coast, a pronouncement that was widely reported and that widened the rift with the War Department. Though federal officials tried to downplay it, it is generally accepted that DeWitt was transferred to become commander of the Army and Navy Staff College in Washington, DC in September 1943 in large part because of his handling of Japanese American exclusion and its aftermath. [7] Ironically, he was replaced by Delos Emmons , who as military commander of Hawai'i, had pursued a very different strategy towards Japanese Americans there. DeWitt retired in 1947.

He lived out his last years in Washington, DC., where he is reported to have joined the Japan-American Society of Washington. [8] John DeWitt died of a heart attack at age 82 on June 20, 1962. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

For More Information

Arlington National Cemetery. "John Lesesne DeWitt, Lieutenant General, United States Army."

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians . Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1982. Foreword by Tetsuden Kashima. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997.

Daniels, Roger. Concentration Camps, North America: Japanese in the United States and Canada during World War II . Malabar, Fla.: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Co., 1981.

Irons, Peter. Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases . New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Robinson, Greg. By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans . Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Footnotes

- ↑ Roger Daniels, Concentration Camps, North America: Japanese in the United States and Canada during World War II (Malabar, Fla.: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Co., 1981), 37–38.

- ↑ Peter Irons, Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 27.

- ↑ Irons, Justice of War , 29–30.

- ↑ Klancy Clark de Nevers, The Colonel and the Pacifist: Karl Bendetsen, Perry Saito and the Incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2004), 85.

- ↑ Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1982), 125.

- ↑ Personal Justice Denied , 221.

- ↑ See for instance, Personal Justice Denied , 222–24; Robinson, By Order of the President , 198–99.

- ↑ Allan R. Bosworth, America's Concentration Camps (New York: W. W. Norton, 1967), 247.

Last updated Dec. 19, 2023, 6:51 p.m..

Media

Media