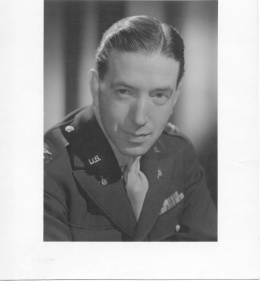

Karl Bendetsen

| Name | Karl R. Bendetsen |

|---|---|

| Born | October 11 1907 |

| Died | June 28 1989 |

| Birth Location | Aberdeen, WA |

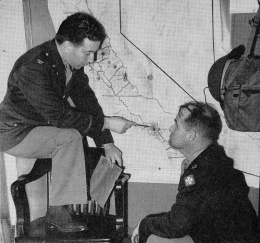

Attorney, forest products company executive and high-ranking federal official, Karl R. Bendetsen (1907–1989) is remembered for his key role in the mass removal and incarceration of the West Coast Japanese Americans during World War II. He claimed in his 1942 military qualification form and in early "Who's Who" entries that he "conceived, drafted and processed Executive Order 9066 " authorizing exclusion of 120,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast; for the next two years he administered the program. During later testimony he denied having any responsibility for the "evacuation" decision.

Before the War

Karl R. Bendetsen, born on October 11, 1907, in Aberdeen, Washington, was the only son of shopkeeper Albert M. Bendetson and Anna Bentson Bendetson, both from families of recently-immigrated Lithuanian Jews. He attended Weatherwax High School in Aberdeen and Stanford University, where he denied his Jewish faith to join Theta Delta Chi fraternity and majored in political science; he earned an AB in 1929 and an LLB in 1932, and joined the Army Reserve Corps. Returning to Aberdeen he practiced general law until May 3, 1940, when he was called to active duty as a captain in the regular army assigned to the Military Affairs Section of the Judge Advocate General's staff. There he drafted and defended the Soldiers and Sailors Civil Relief Act dealing with civil actions which could befall draftees. In April of 1941 he was promoted to major and became assistant to the Judge Advocate General, Major General Allen W. Gullion . He and four other JAG officers assisted in the reactivation of the office of Provost Marshal General, the law enforcement arm of the U.S. Army, which post Gullion assumed. Bendetsen organized and headed the Aliens Division, charged with issues relating to prisoners of war and the internment of enemy aliens. Soon after war was declared, Gullion and Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy , with whom Bendetsen had interacted throughout the prior year, sent Bendetsen to the West Coast to help Lt. General John L. DeWitt to understand his options in controlling enemy aliens. In the sixty days following Pearl Harbor Bendetsen made several such visits and wrote three position papers, one of which became the finding statement for Executive Order 9066, Karl Bendetsen's presence in critical meetings between the War Department leaders and top officials of the Justice Department (far above his rank of major), had a marked influence on the tenor of those meetings. Bendetsen's harsh view of the "Japanese question" differed greatly from that of Assistant Attorney General James H. Rowe Jr. and Edward Ennis , director of the Alien Enemy Control Unit, who sought to defend the civil liberties of the Japanese Americans, particularly of those who were citizens, the Nisei .

Bendetsen's early February 1942 planning paper, titled "Alien enemies on the West Coast (and other subversive persons)," supported General DeWitt's view that the Nisei presented the greatest threat despite the intelligence reports obtained by Office of Naval Intelligence and President Roosevelt's own investigators that did not support this claim. He recommended the designation of military areas "from which all persons who do not have express permission to enter or remain [would be] excluded as a measure of military necessity ." [1]

With Bendetsen's help, DeWitt then wrote a report to Secretary of War Henry Stimson recommending an "evacuation" on the ground that the Japanese on the West Coast would engage in attacks and sabotage because "the Japanese race is an enemy race and while many second and third generation Japanese born on United States soil...have become 'Americanized,' the racial strains are undiluted." Asserting that Japanese raised in the United States would fail to be loyal, DeWitt (and Bendetsen) wrote, "It, therefore, follows that along the vital Pacific Coastal Frontier over 112,000 potential enemies, of Japanese extraction, are at large today. There are indications that these are organized and ready for concerted action at a favorable opportunity. The very fact that no sabotage has taken place to date is a disturbing and confirming indication that such action will be taken." [2]

A Crucial Meeting

After President Roosevelt gave the go ahead to Secretary of War Stimson for mass removal of the Japanese Americans, Bendetsen assisted General Gullion in preparing a draft executive order to present at Attorney General Francis Biddle's home the evening of February 17, 1942. McCloy, Gullion and Bendetsen expected opposition from the Justice Department. Rowe and Ennis launched into an exposition of why a forced removal of citizens would be unconstitutional. Gullion pulled from his pocket the drafted order and read it aloud. Rowe was incredulous and laughed at the general, angering him. Biddle, however, explained that he was deferring to the President and would no longer oppose the removal. [3] Two days later Rowe was required to obtain President Roosevelt's signature on what became Executive Order 9066.

Bendetsen wrote in his 1942 military record (and in his first "Who's Who" entry) that he had "conceived the executive order" and that he "conceived the method, formulated the detailed plans for, and directed the evacuation of 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry from military areas of the West Coast." [4] He saw himself as the architect of military necessity . He wrote to an army friend that he had persuaded Secretary of War Stimson, Assistant Secretary of War McCloy, and Attorney General Biddle that such an exclusion could be seen as constitutional. [5] With Bendetsen's cooperation, General Gullion had successfully insinuated himself into the chain of command between General DeWitt, who commanded troops, and the leaders of the army. When given the opportunity, DeWitt said nothing to Army Chief of Staff Gen. George C. Marshall about the magnitude of the "evacuation" that he was about to propose. [6] By the time Gen. Marshall received Lt. Gen. Mark W. Clark's assessment of the Japanese question recommending only measured and limited action, it was clear that planning for the executive order had bypassed the top brass. [7]

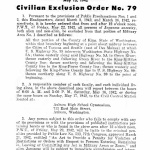

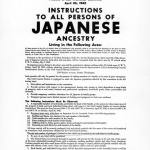

The vaguely-worded executive order allowed a military commander to designate military areas from which any or all persons could be excluded. Many assumed that this order was to be used against enemy aliens, a category that included Italians and Germans as well as Japanese aliens. However the order, as delegated to and promulgated by General DeWitt, was applied to "all persons of Japanese Ancestry, both alien and non-alien." By this order, the latter group, American-born children of Japanese immigrants, were forced to leave the West Coast and were imprisoned without any opportunity to defend themselves in court.

Executive Order 9066

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, Bendetsen received a double promotion to colonel, was named assistant chief of staff (ACS) to DeWitt, and put in charge of the forced removal and incarceration program that he had conceived. He set up offices in the Whitcomb Hotel in San Francisco and enlisted the help of a number of federal agencies. He was an assiduous organizer, a person "always on task," a poised and commanding presence, persuasive and focused on getting the job done. [8] He issued orders in General DeWitt's name and then executed them himself as director of the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA), the agency he had proposed to oversee the forced removal of the targeted "persons of Japanese ancestry" and the establishment of the "assembly and relocation camps." Once the entire Japanese American population was fully removed from Military Areas I and II (the western half of Washington and Oregon, all of California and southern Arizona) and had been transferred into ten prison camps under the jurisdiction of the War Relocation Authority (WRA), the WCCA was dissolved (March 1943). In November 1942 Bendetsen received a Distinguished Service Medal for his leadership of the "evacuation." He continued as ACS and head of the Civil Affairs Division of the Western Defense Command (WDC) until October 1943.

Bendetsen's submission in April 1943 of the Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 was rejected by John J. McCloy because McCloy disagreed with many of General DeWitt's positions therein. Bendetsen participated in the destruction of the original submission and alteration of the report that was finally submitted on June 5, 1943.

After EO 9066 and Subsequent Career

Bendetsen was not promoted to general as he had hoped; after his duty with the Western Defense Command, he served as a high-level civil affairs officer in the invasion and liberation of Europe, working on various planning operations, including Operation Overlord. Later he was deputy chief of staff with the 12th Army Group under Lt. General Omar T. Bradley. He mustered out in December 1945.

After the war, Bendetsen enjoyed considerable success as a civilian administrator of the army and later in the business world. Though his appointment was vigorously opposed by the Japanese American community, Bendetsen served during the Truman administration as assistant secretary of the army for Secretary Gordon Grey, and briefly as under secretary for Secretary of the Army Frank Pace Jr. He joined Champion Paper & Fiber Co. in 1952 and rose to president, CEO and chairman of the board of forest products conglomerate Champion International, retiring in 1972.

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians

In the 1970s, Bendetsen broke a years-long refusal to be interviewed about his role in the forced removal and incarceration of the Japanese Americans, immediately beginning to rewrite history, which he accused the redress supporters of doing in the 1980s. He told Truman Library interviewer Jerry N. Hess that the assets and properties of the Japanese Americans were protected and that incarceration was never intended. [9] In an article for a biographical encyclopedia, he revised his Jewish and Lithuanian origins, giving himself fictitious (perhaps Icelandic) grandparents. [10] He began the practice of denying that he had anything to do with the decision to exclude, or that he took part in important meetings, contending that "of course, I wasn't in high level meetings, I was just a major." [11] In a November 1981 CWRIC hearing, former Justice Arthur J. Goldberg reminded Bendetsen of his first "Who's Who" statement; Bendetsen would not admit to what he conceived, and argued at length that he did his conceiving only after " voluntary evacuation " was shown to be a failure. When forced by Goldberg to acknowledge that there had been a compulsory removal he immediately said, "When they were in the centers, they were free to leave." [12]

Bendetsen's grasp of reality (or commitment to it) was questioned in many of his appearances before commissions or congressional committees in the 1980s; he disagreed with any statement made by former detainees, arguing that they just wished to make a "raid on the Treasury." Appearing before a 1984 House Judiciary Subcommittee investigating David Lowman's claims regarding the MAGIC Cables , Bendetsen made unsupported assertions that the cables "revealed that there were hundreds of espionage nets among persons of Japanese ancestry on the West Coast...[and were] the basis finally of General DeWitt's recommendations." Minutes later he admitted that he doubted DeWitt had any knowledge of the cables, and that he himself hadn't know of them until after the Battle of Europe [in 1945]. [13] In 1988 his wife reported that he had Alzheimer's disease; he died in Washington D.C. on June 28, 1989.

For More Information

de Nevers, Klancy Clark. The Colonel and the Pacifist: Karl Bendetsen, Perry Saito, and the Incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2004.

Footnotes

- ↑ Klancy Clark de Nevers, The Colonel and the Pacifist: Karl Bendetsen, Perry Saito and the Incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2004), 103-104.

- ↑ de Nevers, The Colonel and the Pacifist , 118.

- ↑ Peter Irons, Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese American Internment Cases (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 79 and Kai Bird, The Chairman: John J. McCloy: The Making of the American Establishment (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992), 153.

- ↑ de Nevers, The Colonel and the Pacifist , 313-315. As noted, Bendetsen failed to change his year of birth, incorrectly give as 1908, when he edited this Statement of Military Qualifications in 1942.

- ↑ Ibid., 120-121.

- ↑ Roger Daniels, ed., American Concentration Camps Vol. II (New York: Garland, 1989), transcript, February 3, 1942 conversation between DeWitt and Marshall.

- ↑ de Nevers, The Colonel and the Pacifist , 115 and Roger Daniels, Concentration Camps: North America: Japanese in the United States and Canada During World War II (Malabar, Fla.: Krieger, 1981), 66-67.

- ↑ Lawrence Hewes, Boxcar in the Sand (New York: Knopf, 1957), 182.

- ↑ Oral History Interview with Karl R. Bendetsen, by Jerry N. Hess, Harry S. Truman Library, New York City, NY, October 24, November 9 and November 21, 1972.

- ↑ de Nevers, The Colonel and the Pacifist , 269. Biographical entries in the National Cyclopaedia of American Biography are based on questionnaires completed by individuals or their families.

- ↑ Ibid., 11.

- ↑ Ibid., 280-281.

- ↑ Ibid., 287-288.

Last updated Dec. 11, 2023, 8:08 p.m..

Media

Media