Lordsburg (detention facility)

| US Gov Name | Lordsburg Internment Camp |

|---|---|

| Facility Type | U.S. Army Internment Camp |

| Administrative Agency | U.S. Army |

| Location | Lordsburg, New Mexico (32.3500 lat, -108.7000 lng) |

| Date Opened | June 15, 1942 |

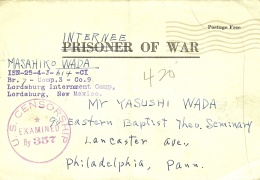

| Date Closed | 1944 |

| Population Description | Held internees of Japanese ancestry transferred from numerous U.S. Army- and Departmen of Justice-run internment camps; also held German nationals, German and Japanese prisoners of war (POWs), as well as U.S. Army soldiers who had been convicted of various offenses. |

| General Description | Located on 1,300 acres of desert land near Lordsburg in southwest New Mexico. |

| Peak Population | 2,500 |

| National Park Service Info | |

The Lordsburg Internment Camp was the largest of the army-run internment camps holding Japanese Americans in the continental U.S. and the only one specifically built to house enemy aliens. It was located outside the small town of Lordsburg, New Mexico in the southwest corner of the state, at an elevation of about 4,000 feet. Lordsburg operated as an internment camp for about a year, from June 1942 to June 1943, and had a peak population of about 1,500. While most of the internees were from the continental U.S., there was a substantial contingent from Hawai'i, as well as a handful from Alaska. Two Issei internees were shot and killed in July 1942 while walking to the camp from the train; there was also a bitter dispute between internees and camp administrators over forced manual labor outside of the camp in the first few months. Over time, internees established a community that included a newspaper and news reporting, religious services, and recreational activities such as gardening, arts and crafts, performing arts, and sports. In the spring and summer of 1943, internees were moved in groups to camps run by the Justice Department—most to one in Santa Fe—in order to clear room for prisoners of war. Lordsburg subsequently held as many as 4,000 Italian and German POWs.

Origins, Layout and Environmental Conditions

The Lordsburg Internment Camp was located on a 1,300 acre site around 2½ miles from the town of Lordsburg in an area Tessa Moening Cencula describes as "one of the most arid spots in the state." Internee and Hawai'i journalist Yasutaro Soga described the the town as "a small, desolate village with a population of about four thousand." The army contracted Tucson-based M.M. Sundt Construction Company to build the camp, which hired many local workers to begin construction in February 1942. The main area of the camp consisted of three separate compounds, each intended to house a battalion of about 1,000 men. Each compound was subdivided into four company areas intended to house about 250 that resembled a block from War Relocation Authority camps. Each company area had eight residential barracks measuring 20 x 110 that were wood framed and covered with tar paper siding. Unpartitioned, inmates slept side-by-side in individual cots. Company areas also included its own mess hall, latrine buildings, and a recreation building and outdoor recreation areas, along with a library, store, infirmary, and various administrative offices. There were about 280 buildings in total. The complex was surrounded by a double-barbed wire fence and guard towers; guards patrolled the perimeter in jeeps mounted with machine guns. Beyond the internee area were administrative buildings, soldiers' barracks to the west, and what Soga described as "a magnificent hospital that seemed out of place" to the south. There was a also a graveyard in which at least three internees who had died at Lordsburg were buried about a thirty minute walk away. [1]

As a newly built camp, Lordsburg internees faced some of the same problems inmates at WRA camps faced. As was the case with many WRA camps, the first arrivals found that the camp was unfinished. Arriving with one of the first groups, internee George Hoshida, a businessman and artist from Hilo, found insufficient numbers of latrines with a single usable faucet for the 250 men in his company. "The grounds were dug up and not yet leveled. Rubbish was strewn around all over," he wrote in his journal. "The dirt dug up dried up into fine dust and was stirred up by the whirlwinds which attacked us every few minutes. We had to cover our mouths and nostrils with wet handkerchiefs to keep the dust out of our lungs and prevent from choking." These dust storms—caused in part by the denuding of the existing vegetation in the process of building the camp—remained an issue for internees throughout. Soga wrote of sandstorms "nearly every day," observing that in severe storms, "I could not distinguish the faces of people a few feet in front of me." Seattle businessman Genji Mihara wrote of the "sultry heat on greenless the desert, no colour of pretty flowers nor charming voice of the singing birds like Missoula," in a July 17 letter to his wife. [2]

Internees—most of whom were from relatively temperate areas on the West Coast or Hawai'i—also struggled with weather that ranged from very hot to very cold, sometimes in the same day. "The heat in here is over hundred every day unbearable, we yearning our northern waterly beautiful scenery in summer," wrote Mihara in a July 12 letter to his wife. Soga observed that after intense heat in August, winter arrived suddenly in October. Fellow Hawai'i internee Hoshida wrote that he "saw frost for the first time in my life" on October 31. By December, it was bitterly cold; after going for a walk on a winter morning, Sogo wrote, "I felt as if my face and ears were being sheared." On May 11, he recorded temperatures of 40° in morning and and 90° at noon. Beyond the weather, internees noted swarms of mosquitoes in the fall, as well as flies, ants, snakes and scorpions. Despite the desolate surroundings, internees also found some beauty. "The nature of New Mexico especial the clouds are so beautiful this morning after the rain we saw the golden clouds that looked like a flame in the eastern sky," wrote Mihara in a September 12 letter, "we Japanese who live nature, could enjoy life where we go." [3]

Internee Population

The internee population at Lordsburg was entirely male and almost entirely Issei. The first group arrived on June 15, and most internees arrived by the end of July. The largest group of 613 came from the Fort Lincoln Internment Camp in Bismarck, North Dakota, in July. About 250—many from Hawai'i or Alaska—came from Fort Sam Houston in Houston, Texas, and smaller groups came from the Missoula , Montana; Santa Fe , New Mexico; Fort Bliss , Texas; and Fort McDowell (Angel Island), California detention facilities. The population peaked at just over 1,500 in November 1942. Of this number, about 250 came from Hawai'i. Later, on October 28, around fifty Japanese POWs, most of whom had been captured from a submarine sunk during the Battle of Midway—and some of whom had taken part in the attack on Pearl Harbor—arrived and were housed amongst the internees, and according to Yasutaro Soga, the two groups "gradually became friendly." After a conflict with camp authorities over the display of a Japanese flag at a November 3 celebration of the emperor's birthday, the POWs were moved to the Livingston , Louisiana, Internment Camp. A group of about twenty American soldiers detained for disciplinary reasons were also held at Lordsburg in November. On November 26, one of these detainees got drunk and attacked two of the internees with a knife, injuring one, though not seriously. In February 1943, officials at the Gila River War Relocation Authority concentration camp rounded up so-called "agitators" during the loyalty questionnaire period. Fifteen Issei from this group were subsequently sent to Lordsburg. [4]

Given the size of the internee population, only two of the three compounds at Lordsburg were used. Internees were organized into two battalions, the 2nd and 3rd, each assigned its own compound. The 2nd Battalion was made up of the 5th through 8th Companies and the 3rd Battalion the 9th through 12th. According to the journalist Soga, the camp population included about a hundred clergymen, most of whom were Buddhist, with others from Shinto or Christian churches, or from one of the new Japanese religions. He also counted thirty-one journalists including the heads of many of the West Coast Japanese language newspapers, along with a few members of the Tokyo Club, a notorious crime syndicate, whom he found to be "quiet and cooperative." [5]

Internee Life at Lordsburg

Run like a POW camp by the army, internee life at Lordsburg was regimented in many ways. A bugle awoke the internees at 6 am and lights went out at 10 pm. They took their meals in company mess halls at set times. In the first weeks, the administration conducted bed checks twice a day, by that was later reduced to a weekly roll call on Saturdays after June 27. Living in close quarters in the barracks, privacy was minimal and the problems of communal living came to the fore. "My barracks was like a zoo at night," recalled Soga. "Loud snoring could be heard from one end to the other," while others loudly played games or sang. He noted a few internees who refused to bathe and those who suffered nervous breakdowns. Internees argued over opening windows or whether or not to turn on the gas heaters. Mess hall food seemed generally to get good reviews, with Mihara reporting "good food," Quaker missionary and Nikkei advocate Herbert Nicholson calling the food "excellent" based on an October visit to the camp, and Soga writing that while "[s]ome complained about the meals, but I thought they were fairly good," while also acknowledging that "we were forced once in a while to eat sand with our rice" due to the dust storms. [6]

Mail was the internees' lifeline to the outside and was also strictly policed. Inmates were allowed two letters of up to twenty-four lines and one postcard per week, with various rules for what they could write about; both incoming and outgoing mail would be checked by censors. The main post office just outside the fence also served as a meeting area for visitors, who were kept separate from the internees by a wire net. Spoken exchanges could only be in English. Internees were issued $1 in monthly coupons (later raised to $3) to be spent in the canteens, mostly for toiletries, food items, cigarettes, postage stamps, and, eventually, beer, limited to one bottle per day. Some internee camp workers were also paid (at a 10¢ per hour rate) including cooks, doctors, barbers and canteen staff; leaders of the inmate government (described below) were also paid. Inevitably, there was some discord over workers being paid but not others. The hospital served both military personnel and internees and was headed by military officers. Internee doctors also staffed the hospital as well as clinics in each of the company areas. Nicholson called it "a fine hospital where good care is taken of the sick." [7]

Within the framework of this regimentation, internees were able to put together their own religious, cultural and recreational programs. Given the preponderance of middle-aged Issei community leaders at Lordsburg, news became a preoccupation of many. A twice weekly Japanese language newspaper, the Lordsburg Jiho , first appeared on August 26. Keitaro Kawajiri of Seattle was the editor-in-chief and Kenji Kasai the general manager; subscriptions were 10¢ a month. Internees also created their own news broadcasts, with popular broadcasters drawing overflow crowds. Internee experts lectured on various topics to appreciative audiences. Various religious groups formed out of the large number of religious leaders who had been interned. Funerals would be conducted by dozens of clerics, something reserved only for the most important people on the outside. "Upon seeing this spectacle, someone joked, 'If you have to die, now is the time'," wrote Soga, noting this internee's black humor. Soga, Hoshida, and Mihara all noted the huge November 3 celebration, a "grand picnic was held by the inmates of the whole camp of 1600 internees at the Compound Three ball ground," as described by Hoshida that included sumo and various games. Other large celebrations were held to commemorate other significant Japanese dates. There were talent shows and theatrical presentations, various sports, Japanese poetry groups, and arts and crafts among many other activities. Gardening was also a popular pastime. A November 1942 visitor from the International Red Cross reported that gardening was "the principal occupation of the internees" who "have laid out striking decorative gardens and very fertile vegetable gardens...." Mihara wrote to his wife in October about a internee-made park with a new "cute little arched bridge" that was painted red and and "pleasing to the eyes. Certainly it adds much to the beauty of the camp." Internees even composed a song about life at Lordsburg. It is clear that internees did their best to improve the quality of their lives while interned to whatever extent was possible. [8]

Administration, Self-Government, and Unrest

The initial commander of the camp was Lt. Col. Clyde A. Lundy, who presided over a staff of 110, including ten officers. He soon became known for hosting parties for the officers, keeping a safe filled with liquor in his office, and for allegations of mishandling profits from the canteen. Cencula writes that, "most of these men did not consider Lordsburg to be a 'choice assignment, and Lundy's leadership reportedly left much to be desired." On the internee side, various officers were elected, headed by governors and vice-governors of the two battalions and mayors of each of the companies, along with various other lower offices. Top office holders received the same wages as other key internee workers in the camp. Given that many of the internees were themselves community leaders, holding these offices often proved to be a thankless task. Elected as on of the company mayors, Mihara noted in his limited English the "many self bit shots" among the internees who "make me dizzy to unify their difficult difference" in one of his letters home. [9]

Lundy's tenure was marked by two major conflicts with internees. Shortly after the arrival of the first internee groups in June, Lundy ordered them to perform punishing manual labor in midday heat in apparent violation of the Geneva Convention. Various groups among these internees decided not to obey these orders. Lundy at times jailed the mayors of the three battalions and held entire battalions under barracks arrest, while their efforts to contact the Spanish consul (designated to represent the interests of interned Japanese nationals) were initially to no avail. A consular delegation visited in August, though it was not until December that the consul produced a report verifying many of the inmates' charges. Lundy had in the meantime agreed to abide by the convention and eventually released those under barrack confinement. Hoshida, who was in one of the affected companies, wrote of being "confined within the barracks with guards stationed outside to prevent us from going outside. All privileges such as canteen service, light at night, and going outside, except to the latrine... were denied to us strikers." When he and his group agreed to return to work, he noted that the "commander definitely seemed bent on revenge and punishment on us who had disobeyed his wishes." While this labor dispute was ongoing, the camp was shocked by another incident in which two elderly Issei inmates, Toshio Kobata and Hirota Isomura, were shot to death by a guard while en route from the train to the camp entrance on July 27. The shooter, Pfc. Clarence A. Burleson, was acquitted of manslaughter after a one-day trial. (See Homicide in camp for more on the shootings.) [10]

Lundy was eventually removed from his post on December 17, replaced by Col. Louis A. Ledbetter. Though there were still some instances of misbehavior by guards—including multiple instances of guards firing guns in attempts to intimidate internees perceived to be resisting orders—conditions and relations between internees and administration seemed to improve subsequently. Hoshida noted a February 18 incident in which a guard shot at the feet of an internee foreman over a misunderstanding of duties, noting that the new regime recognized the wrong done and demoted the guard. "The present commander seems to be a very understanding man, unlike the first," he wrote. Soga wrote that "the attitude of the guards toward us was good and we had no serious complaints," while also noting the shooting incidents. [11]

Closing and Aftermath

About 90% of the internees eventually transferred to the Santa Fe, New Mexico, Internment Camp which was run by the Department of Justice. The first group of around 375 bound for Santa Fe left on March 23 or 24, with the rest moving between June 14 and 23. About a hundred went to the Crystal City , Texas, camp to be reunited with families, while a handful moved to the Kooskia , Idaho, internee work camp. Once cleared of internees, Lordsburg was converted for use as a POW camp, initially holding Italian POWs until the summer of 1944, then German POWs, with the number topping out at about 4,000. After the war, the buildings at the site were auctioned off. The site, now located off POW Road, is privately owned today. The Hidalgo County Museum has an exhibit about the camp. [12]

For More Information

Cencula, Tessa Moening. "The Lordsburg Internment Camp." In Confinement in the Land of Enchantment , ed. Sarah R. Payne. Fort Collins, Colo.: Colorado State University, Public Lands History Center, [2017].

Culley, John J. "Trouble at the Lordsburg Internment Camp." New Mexico Historical Review 60.3 (July 1985): 225-48.

Hoshida, George and Tamae. Taken from the Paradise Isle: The Hoshida Family Story . Ed. Heidi Kim. Foreword by Franklin Odo. Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 2015.

Kanzaki, Stanley N. The Issei Prisoners of the San Pedro Internment Center . New York: Vantage Press, 2008. [Novel set in a fictional internment camp based on Lordsburg.]

Kashima, Tetsuden. Judgment Without Trial: Japanese American Imprisonment during World War II . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002.

Mihara Collection , Densho Digital Repository.

Okawa, Gail Y. Remembering Our Grandfather's Exile: U.S. Imprisonment of Hawai'i's Japanese in World War II . Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2020.

Soga, Yasutaro [Keiho]. Life behind Barbed Wire: The World War II Internment Memoirs of a Hawai'i Issei . Translated by Kihei Hirai. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2008.

Footnotes

- ↑ Tetsuden Kashima, Judgment Without Trial: Japanese American Imprisonment during World War II (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002), 115; Tessa Moening Cencula, "The Lordsburg Internment Camp," in Confinement in the Land of Enchantment , ed. Sarah R. Payne (Fort Collins, Colo.: Colorado State University, Public Lands History Center, [2017]), 26–28; Yasutaro [Keiho] Soga, Life behind Barbed Wire: The World War II Internment Memoirs of a Hawai'i Issei , translated by Kihei Hirai (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2008), 74–75, 100–01, 120; George Hoshida, "Our Barrack, Lordsburg Internment Camp," July 4, 1942 George Hoshida Collection, Japanese American National Museum, accessed on Apr. 2, 2020 at http://www.janm.org/collections/item/97.106.1Q/ .

- ↑ George and Tamae Hoshida, Taken from the Paradise Isle: The Hoshida Family Story , ed. Heidi Kim (Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 2015), 95; Soga, Life behind Barbed Wire , 117; Letter, Genji Mihara to Katsuno G. Mihara, July 17, 1942, Densho Digital Repository, Courtesy of the Mihara Family Collection, accessed on Apr 2, 2020 at http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-140-116/ .

- ↑ Letters, Genji Mihara to Katsuno G. Mihara, July 12, Sept. 7, 12, and 24, and Oct. 12, 1942, Densho Digital Repository, Courtesy of the Mihara Family Collection, all accessed on Apr. 2, 2020 at http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-140-115/ , http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-140-131/ , http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-140-132/ , http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-140-135/ , and http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-140-140/ ; Soga, Life behind Barbed Wire , 99, 118; Hoshida, Taken from the Paradise Isle , 115.

- ↑ Kashima, Judgment Without Trial , 115, 196–97, 260n37; Barbara Wyatt, ed., Japanese Americans in World War II: National Historic Landmarks Theme Study (Washington, D.C.: National Historic Landmarks Program, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2012), 182; Soga, Life behind Barbed Wire , 72, 103, 116–17; Cencula, "The Lordsburg Internment Camp," 27; Hoshida, Taken from the Paradise Isle , 115; Letter, Robert H. Lowie to Dorothy Thomas, Feb. 18, 1943, The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement: A Digital Archive, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder W 1.23 http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/jarda/ucb/text/cubanc6714_b295w01_0023.pdf .

- ↑ Kashima, Judgment Without Trial , 115; Soga, Life behind Barbed Wire , 75, 88–89, 91, 97.

- ↑ Cencula, "The Lordsburg Internment Camp," 29–30; Kashima, Judgment Without Trial , 115; Soga, Life behind Barbed Wire , 76, 100–02, 115; Letters, Genji Mihara to Katsuno G. Mihara, Aug. 4 and Oct. 2 and 16 1942, Densho Digital Repository, Courtesy of the Mihara Family Collection, accessed on Apr. 2, 2020 at http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-140-122/ , http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-140-137/ and http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-140-141/ ; H. V. Nicholson, letter to editor, Pacific Citizen , Oct. 15, 1942, 4.

- ↑ Soga, Life behind Barbed Wire , 75, 93, 112–16, 121; Letters, Genji Mihara to Katsuno G. Mihara, July 12 and Oct. 2, 1942, Densho Digital Repository, Courtesy of the Mihara Family Collection, http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-140-115/ and http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-140-137/ ; Kashima, Judgment Without Trial , 115–16; Nicholson, letter to editor.

- ↑ Soga, Life behind Barbed Wire , 88–91; 104; Hoshida, Taken from the Paradise Isle , 111, 116; Letter, Genji Mihara to Katsuno G. Mihara, Oct. 5, Oct. 16, Nov. 9, 1942, and Feb. 20, 1943, Densho Digital Repository, Courtesy of the Mihara Family Collection, accessed on Apr. 2, 2020 at http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-140-138/ , http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-140-141/ , http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-140-148/ , http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-140-161/ ; Kashima, Judgment Without Trial , 115; Cencula, "The Lordsburg Internment Camp," 30–32; Gail Y. Okawa, Remembering Our Grandfather's Exile: U.S. Imprisonment of Hawai'i's Japanese in World War II (University of Hawai'i Press, 2020), 113–14; Minako Waseda, "Extraordinary Circumstances, Exceptional Practices: Music in Japanese American Concentration Camps," Journal of Asian American Studies 8.2 (June 2005), 194.

- ↑ Cencula, "The Lordsburg Internment Camp," 29–30; Interview with Richard S. Dockum, conducted by Paul F. Clark and Mollie M. Pressler on March 18, 1977 for the California State University, Fullerton Oral History Program Japanese American Project, p. 6, in Japanese American World War II Evacuation Oral History Project, Part II: Administrators , edited by Arthur A. Hansen, accessed on May 20, 2020 at http://content.cdlib.org/view?docId=ft7199p03k;NAAN=13030&doc.view=frames&chunk.id=Richard%20S.%20Dockum&toc.depth=1&toc.id=0& ; Soga, Life behind Barbed Wire , 75; Letter, Genji Mihara to Katsuno G. Mihara, Aug. 11, 1942, Densho Digital Repository, Courtesy of the Mihara Family Collection, accessed on Apr. 2, 2020 at http://ddr.densho.org/ddr-densho-140-124/ .

- ↑ Kashima, Judgment Without Trial , 196–203; Cencula, "The Lordsburg Internment Camp," 33, 36; Hoshida, Taken from the Paradise Isle , 96–101; Okawa, Remembering Our Grandfather's Exile , 88–94.

- ↑ Cencula, "The Lordsburg Internment Camp," 38; Richard S. Dockum interview, 7; Kashima, Judgment Without Trial , 204–05; Hoshida, Taken from the Paradise Isle , 159–61; Soga, Life behind Barbed Wire , 117.

- ↑ Soga, Life behind Barbed Wire , 121, 123, 129; Kashima, Judgment Without Trial , 118; Cencula, "The Lordsburg Internment Camp," 39; Wyatt, ed., Japanese Americans in World War II , 182–83.

Last updated July 17, 2021, 5:15 p.m..

Media

Media