Music in camp

The incarceration of Japanese Americans interrupted their socio-economic development and identity. Yet, it provided them with exceptional opportunities for music making. For those incarcerated, music was an important means for creating hope, cohesion, resistance, and a sense of identity; yet for the camp authorities, the same music was understood to be a mechanism for relieving the inmates' anger and anxiety and controlling their behavior. Promoted by both the Japanese American inmates and the camp authorities for their own benefits, music thrived in concentration camps, fulfilling multiple functions.

[1]

Context of Musical Activities in the Camps

The camp administrative bureaus, under the jurisdiction of the War Relocation Authority (WRA), established a Recreation Department and a Music Department in each camp and employed teachers for various recreational and musical activities. They also established recreation halls in each block and even amphitheaters in some camps. This kind of support was part of the WRA's strategy to regulate the inmates' behavior and thought. The circumstances of camp life also created conditions that fostered musical activity. First, due to the highly concentrated Japanese population, instructors in a wide variety of musical types, especially of Japanese genres, became accessible to many. Second, liberated from the stresses and demands of earning an independent living, the inmates had an abundance of free time. Finally, they urgently sought out music as a diversion from the grim reality and tensions of camp life. Consequently, many of them began to practice some form of performing arts for the first time in the camps.

Published literature provides few details about the Justice Department and U.S. Army internment camps, which mostly imprisoned Issei and Kibei Nisei community leaders from Hawai'i. The available data, however, suggest that at Santa Fe (New Mexico) and Fort Missoula (Montana), a self-governance system analogous to that in the WRA camps, including recreation and music departments, was adopted. [2] The camp authorities in these camps also not only approved but encouraged sports and entertainments. [3]

Overall the camp environments served to both revitalize Japanese music and promote Western classical and American popular music among Japanese Americans. The only exception occurred at Tule Lake (California), where music was used as a means of resistance, and, consequently, faced the direct opposition of the WRA.

Vitalization of Japanese Music Practices

Every art that had been practiced in Japanese American communities before the war continued on in many, if not all, of the camps. The musical genres performed in the camps include various types of Japanese plays (such as kabuki), naniwa-bushi (narrative music), gidayū (narrative music accompanied by the shamisen), biwa (narrative music accompanied by a lute-type instrument), classical dance, koto (zither), nagauta (vocal music accompanied by the shamisen), shakuhachi (bamboo flute), and yōkyoku (vocal music in nō theater) (see Figure 1).

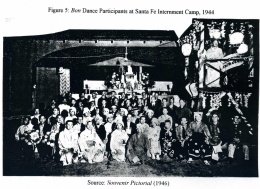

Kabuki: Japanese plays, particularly kabuki, were the most popular entertainment for the Issei. A great number of inmates collaborated in dividing the responsibilities for such areas as acting, music, narrating, stage production, dance instruction, and scriptwriting. Japanese plays were also very popular at the Lordsburg and Santa Fe internment camps in New Mexico. The Japanese inmates from Hawai'i and the mainland formed the Hinomoto Troupe at Lordsburg in 1942 (see Figure 2). Its activities were continued in Santa Fe as most of the members were transferred there by 1944. When no shamisen was available, the performers used kuchi-jamisen–vocal imitation of the shamisen sounds–as the musical accompaniment for their plays. [4] Some costumes and props were sent from Hawai'i, [5] but many others had to be handmade out of limited materials; the bamboo rings attached to soy sauce barrels sent from Japan were used as the bases of wigs, [6] while the hair was made by Manila rope cut into three-foot-long pieces or so, soaked in water to separate the fibers, and then dyed the desired colors. [7]

Japanese Classical Dance, Koto, and Shakuhachi

Japanese classical dance and koto, which were popular before the war, continued to thrive in the camps. For instance, at Rohwer Kansuma Fujima, a Nisei teacher, taught about forty students between the ages of nine and sixteen. [8] At Tule Lake, Mitsusa Bandō (formerly Misa Bandō), also a Nisei teacher, taught a group of about 140 students, mostly between the ages of eight and ten but with a range that extended from a three-year-old Sansei (third-generation) to a senior Issei (see Figure 3). [9] In some cases, such teaching activities were incorporated into the Recreation Department programs and the teachers were paid a monthly salary. Fujima and Bandō were paid nineteen dollars a month, which was second only to the twenty dollars paid to the doctors at Rohwer, and was the highest at Tule Lake. Some dance props were handmade by the inmates: they used a tin stove-pipe as the base of a wig, to which a rope shredded and painted black with shoe polish was attached as the hair, while stage backdrops were made by sewing together gunny sacks and painting scenery on them. [10] Although some inmates were able to ask their non-Japanese friends to store their musical instruments upon their departures and eventually have them sent or brought to the camp, similar creative efforts were also made by the koto and shakuhachi practitioners in the camps. The koto plectrums were made by carving a toothbrush, a chip of wood, or cow bones and horns. [11] Shakuhachi were made from hickory trees [12] or out of water pipes. [13]

Ondo (bon dance): Ondo (a type of Japanese folk music and dance) was performed in the camps not only during obon (a Buddhist event to console the souls of the deceased, which is a typical occasion for ondo dancing), but also during other summer festivities, such as Independence Day and Labor Day celebrations, or just by itself as an independent event. It was not unusual for camp ondo events to draw several thousand dancers and spectators. Bon dances were also enjoyed at the Santa Fe Justice Department Camp (see Figure 4). [14]

Engei-kai: As before the war, engei-kai, which can be likened to talent shows, held in the camps consisted of a variety of Japanese performing arts interspersed with a few non-Japanese acts, such as piano, harmonica, American popular songs, and Hawaiian dance. The ages and repertoires of the camp engei-kai performers ranged from five to six-year-old girls performing Japanese classical dance, to young adults giving vocal performances of Japanese popular songs, to over seventy-year-old seniors playing traditional Japanese music.

Serving the entertainment and socialization needs of the inmates, engei-kai were held frequently–at least once a month in every camp and, in the more extreme cases, almost daily. [15] To accommodate larger audiences, amphitheaters were built in several camps including at Rohwer, Tule Lake, Poston , Gila River , and Santa Fe. At Poston, the residents built a gorgeous outdoor stage patterned after a traditional Japanese theater. [16]

Camp Songs: The Issei created camp songs to enhance fellowship among the inmates and to inspire them to overcome shared hardships. The initiative for creating these songs was taken either by the Japanese-language division of the camp newsletter or by the Issei Recreation Department. Contests were held, soliciting song lyrics from the inmates, and a winning song was selected from among all of the entries by a judging committee. The qualities of patience and docility extolled in the lyrics reflect a traditional Japanese mentality, which was prevalent among the Issei. The camp songs composed by the inmates from Hawai'i are more sentimental in content than those created in the WRA camps, expressing their loneliness in being separated from their families in Hawai'i. [17]

Japanese Culture as a Means of Resistance: Ultra-Nationalism at Tule Lake

Tule Lake became a segregation camp for the inmates labeled "disloyal" as a result of the so-called "loyalty questionnaire" administered in 1943. In this camp, a small group of pro-Japan ultra-nationalists promoted various types of traditional Japanese cultural activities including classical dance and yōkyoku. This was part of their agenda to better prepare people for eventually returning and assimilating to Japan. This cultural revival movement, however, had become too aggressive and militaristic, and even threatening to other inmates. By July 1945, some 1,500 radical Tule Lake inmates were re-segregated as "undesirables" at a separate camp. Thus, the Japanese cultural revival at Tule Lake, which exceptionally used Japanese culture as a means of resistance, was short-lived and not successful. [18]

Promotion of Western Classical and American Popular Music

As the WRA's policy was to "Americanize" the Japanese Americans, Western classical and American popular music activities were both encouraged and supported. The Music Department of each camp, funded by the WRA, offered music appreciation classes and lessons in piano, violin, voice, choir, and other musical pursuits. Instructors of Western classical music consisted of Japanese American inmates as well as non-Japanese sent from outside. [19]

Much more popular than Western classical music, however, was ballroom dancing. Every event–from national holidays to the celebration of the completion of new construction projects and the formation of charities–became an occasion for dancing. Some camps also hosted weekly Saturday night dances and dance classes. Soon, almost every camp had one or more jazz bands that provided live music for dancing. [20] As early as the late 1920s, as a part of mainstream American culture, big band jazz, coupled with ballroom dancing, captured the interest of the Nisei youth. The formation of numerous camp bands was an extension of the burgeoning Nisei bands in the prewar era. In addition to funds from the Recreation Department, the members of dance bands received a monthly salary in some camps. At Heart Mountain the members of the George Igawa Dance Band were paid twelve dollars a month as unskilled laborers, while those of Down Beat at Tule Lake received fourteen dollars a month, plus five dollars for an evening's work. Some of the dance bands also enjoyed the privilege of leaving camp grounds to perform for neighboring townspeople, as a means of improving public relations. [21] The camp bands, which performed the hit tunes of Glenn Miller, Tommy Dorsey, Artie Shaw, and others, directly linked the incarcerated Nisei to mainstream American culture. Performing and dancing to these swing repertoires, young Japanese Americans, consciously or not, were affirming their identity as Americans. [22]

For More Information

Conrat, Maisie and Richard. Executive Order 9066: The Internment of 110,000 Japanese Americans . Los Angeles: UCLA Asian American Studies Center Press, 1992.

Furuya, Suikei. Haisho tenten . Honolulu: Hawai taimususha, 1968. Translated as Internment from Camp to Camp . Honolulu: Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai'i, forthcoming, 2013.

Nishimoto, Richard S. Inside an American Concentration Camp: Japanese American Resistance at Poston, Arizona . Edited by Lane Ryo Hirabayashi. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1995.

Sōga, Keihō. Tessaku seikatsu . Honolulu: Nippu jijisha, 1948. Translated as Life behind Barbed Wire: The WW II Internment Memoirs of a Hawaii Issei . Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2007.

Toyo Miyatake: Infinite Shades of Gray/Moving Memories . DVD. Produced by Karen L. Ishizuka, directed by Robert A. Nakamura. Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum, 2002. [Includes a video clip showing the bon dance held at a camp.]

Waseda, Minako. "Extraordinary Circumstances, Exceptional Practices: Music in Japanese American Concentration Camps." Journal of Asian American Studies 8.2 (2005): 171-209.

Weglyn, Michi. Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America's Concentration Camps . New York: Hill and Wang, 1993.

Words, Weavings & Songs . VHS. Produced and directed by John Esaki. Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum, 2002. [Partly features Mary Nomura Kageyama, a Nisei jazz singer at Manzanar, and includes some video clips of the camp dance events.]

Yoshida, George. Reminiscing in Swing Time: Japanese Americans in American Popular Music: 1925-1960 . San Francisco: National Japanese American Historical Society, 1997.

Footnotes

- ↑ The information provided here is largely based on my interviews and examination of the following camp newsletters published by the inmates themselves: Manzanar Free Press of Manzanar, California, Tulean Dispatch of Tule Lake, California, Gila News-Courier of Gila River, Arizona, Poston Chronicle of Poston, Arizona, and Rohwer Outpost of Rohwer, Arkansas. For more information on music in the camps, see Minako Waseda, "Extraordinary Circumstances, Exceptional Practices: Music in Japanese American Concentration Camps," Journal of Asian American Studies 8.2 (2005): 171-209.

- ↑ Suikei Furuya, Haisho tenten (Honolulu: Hawai taimususha, 1968), 263–65, 290–94.

- ↑ Souvenir Pictorial , a pictorial book published in Honolulu by former Santa Fe inmates, 1946.

- ↑ Keihō Sōga, Tessaku seikatsu (Honolulu: Nippu jijisha, 1948), 161.

- ↑ Harry Urata, interview, Honolulu, Hawai'i, Oct. 17, 2000.

- ↑ Since the internment camps detained Japanese nationals, the Japanese government and relief organizations for overseas Japanese sent Japanese food items and books to the camps during the war.

- ↑ Hawaii Hochi , Sept. 29, 1987.

- ↑ Kansuma Fujima, telephone interview, Nov. 3, 2000.

- ↑ Tulean Dispatch , Sept. 24, 1942; Mitsusa Bandō [formerly Misa Bandō], telephone interview, Nov. 11, 2000.

- ↑ Kansuma Fujima, telephone interview, author's translation, Nov. 3, 2000.

- ↑ Kayoko Wakita, interview, Los Angeles, Aug. 6, 1994.

- ↑ Gyokuei Matsuura, interview, Honolulu, Oct. 11, 2000.

- ↑ Furuya, Haisho tenten , 164.

- ↑ Sōga, Tessaku seikatsu , appendix 5.

- ↑ In Rohwer, engei-kai were held by each block. Because there were more than forty blocks in the camp, engei-kai were held almost every day in one block or another, Rohwer Outpost , March 13, 1943.

- ↑ A picture of this theater is included in Richard S. Nishimoto, Inside an American Concentration Camp: Japanese American Resistance at Poston, Arizona , ed. Lane Ryo Hirabayashi (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1995), 89.

- ↑ The lyrics and their English translations of some camp songs are found in Waseda, "Extraordinary Circumstances," 192, 194.

- ↑ For more information on the cultural revival movement at Tule Lake, see Michi Weglyn, Years of Infamy: The Untold Story of America's Concentration Camps (New York: Hill and Wang, 1993), chapter 12.

- ↑ Tulean Dispatch , Oct. 28, 1942; Manzanar Free Press , Oct. 8, 1942; Poston Chronicle , March 24, 1943.

- ↑ The dance parties were held so frequently in the camps that live music was not always available. As an alternative, recorded music was played over the PA system.

- ↑ George Yoshida, Reminiscing in Swing Time: Japanese Americans in American Popular Music: 1925-1960 (National Japanese American Historical Society, 1997), 153.

- ↑ Yoshida, Reminiscing in Swing Time , 125. For more information on the camp jazz bands, see chapter 3 of Yoshida. Words, Weavings & Songs (VHS) partly features Mary Nomura Kageyama, who was a Nisei jazz signer at Manzanar.

Last updated July 22, 2020, 3:53 p.m..

Media

Media