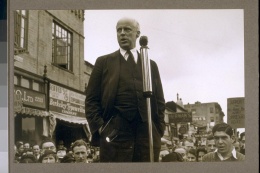

Norman Thomas

| Name | Norman Mattoon Thomas |

|---|---|

| Born | 1885 |

| Died | 1968 |

| Birth Location | OH |

Norman Mattoon Thomas (1885–1968), leader of the U.S. Socialist Party and six-time presidential candidate, was the only national political figure to take a public position against Executive Order 9066 . In writings and public speeches, he denounced mass removal as "totalitarian justice." Thomas was also active in organizational efforts. He circulated a petition calling for immediate hearings for Japanese Americans, and he unsuccessfully pressed the American Civil Liberties Union to take court cases challenging Executive Order 9066.

Born in Ohio, Thomas attended Princeton University and in 1911 became a Protestant minister. Attracted to doctrines of Christian socialism, he joined the Socialist Party during World War I. Following the war, he helped found the League for Industrial Democracy and the American Civil Liberties Union. In 1928, Thomas was first selected as the Socialist Party's presidential candidate, and his campaigns brought him acceptance as leader of the Party. Throughout the 1930s, he spoke out on behalf of Democratic Socialism, economic justice, birth control, and equal rights for Blacks, and opposed both Soviet communism and fascism. In 1940, he joined the America First Committee, and worked to prevent U.S. entry into World War II.

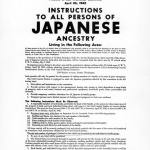

Following Pearl Harbor, Thomas announced his support for U.S. participation in the war, but was forced to spend considerable time justifying his prewar isolationism. Meanwhile, he organized the Post War World Council to promote postwar planning and focused on defending civil liberties in wartime. It was because of this concern about government abuse of power that Thomas was propelled into action in support of Japanese Americans. Although Thomas began receiving information about injustice against Issei and Nisei by early January 1942, he took no immediate action. However, after receiving news of Executive Order 9066, he made immediately made a series of public speeches denouncing mass removal, drafted a short article opposing it for the Socialist Party newspaper The Call , and contacted all the people on his mailing list to ask them to write the government in protest.

In early May 1942, Thomas drafted a petition through the Post War World Council that called for the immediate rescission of Executive Order 9066, which it said, "approximates the totalitarian theory of justice practiced by the Nazis in their treatment of the Jews." The letter demanded immediate civilian boards be set up for both Issei and Nisei, so that the loyal could return to their homes. Within a few weeks, over 200 people signed the petition, including such renowned figures as John Dewey, Reinhold Niebuhr, Ruth Benedict, and W.E.B. DuBois. Meanwhile, as a board member of the American Civil Liberties Union, Thomas signed a group letter asking the President to establish hearing boards. He was greatly disappointed when the ACLU resolved not to challenge Executive Order 9066. Although he backed the cases brought by ACLU lawyers against the government's unequal targeting of Japanese Americans, he complained bitterly that all such challenges missed the essential issue and would fail.

On June 18, 1942, Thomas called a meeting in New York to discuss "the Japanese Question" and organize opposition to mass removal. A number of liberal groups sent representatives. At the meeting, Mike Masaoka of the JACL stated that the treatment of Japanese Americans was "a test of democracy" and warned, "If they can do that to one group they can do it to other groups." [1] With Masaoka's support and that of ACLU director Roger Baldwin, Thomas introduced a resolution calling for the immediate establishment of hearing boards to determine the loyalty of the "evacuees" and warning against the "military internment of unaccused persons in concentration camps."

The resolution was challenged, however, by members of the Japanese American Committee for Democracy , a New York-based antifascist group closely aligned with the Communist Party, who introduced a counterresolution expressing approval of the Order and charging that criticism of the government "hampered the war effort." Although the JACD resolution was defeated handily by those assembled, the meeting settled on a weak compromise resolution avoiding criticism of the government.

Unable to win support for his case from liberal or leftist groups, Thomas turned to the press. In July 1942 he published the pamphlet, Democracy and Japanese Americans , which laid out in detail the facts behind the "evacuation" and described the difficult conditions facing Japanese Americans in the assembly centers . The last several pages were devoted to a program to wind up the camps and promote immediate resettlement , including a provision to reimburse the dispossessed Japanese Americans through government grants of land. Thanks to the distribution efforts of the Japanese American Citizens League, plus Thomas's Socialist Party colleagues, the pamphlet enjoyed wide circulation. Its influence was limited, however, by attacks from army officials, who unsuccessfully sought to discredit the information contained in the pamphlet, and from Nisei communist Karl Yoneda , confined at Manzanar , who sent a letter attacking Thomas to the San Francisco Chronicle .

Shortly after the pamphlet's release, Thomas wrote an extended article, "A Dark Day for Liberty," in the liberal Protestant weekly Christian Century , in which he explained that the President had granted the army "wholly totalitarian controls over American citizens." Thomas poured out the frustration and fear he felt over the difficulties he experienced in finding allies against the creation of "concentration camps" for the expropriated Japanese: "In an experience of nearly three decades I have never found it harder to arouse the American public on any important issue than this."

In addition to his organizing efforts, Thomas corresponded with numerous inmates, including Hideo Hashimoto and Sam Hohri. He also took aim against government censorship. In summer 1942, inmate Kay Hirao smuggled Thomas copies of "The Evacuee Speaks," a clandestine uncensored newsletter circulated by samidzat in the Santa Anita Assembly Center . Thomas undertook to copy it and share it with his friends. Meanwhile, K. Conrad Hamanaka, editor of The Grapevine , the official newspaper of the Fresno Assembly Center , sent Thomas a copy of officially censored stories. Thomas protested vainly to Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy . He subsequently labored to place Hamanaka's articles in magazines and corresponded with Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee founder Kiyoshi Okamoto.

Thomas continued to advocate justice for Japanese Americans throughout the war years. He maintained a steady stream of articles against confinement in The Socialist Call , and included in his public speeches the needs to help resettle the camp inmates. During his 1944 presidential campaign, he visited the West Coast and defied hostile local opinion by calling for the end of exclusion and the return of inmates to their homes. Because of his actions, a number of Nisei joined the Socialist Party.

Thomas continued into the postwar years as Socialist Party leader, and ran for President on the Socialist ticket one final time in 1948. During the McCarthy period, he publicly defended civil liberties and the right to dissent, and became an elder statesman of the American left. In his last years, he emerged as a critic of the Vietnam War.

For More Information

Robinson, Greg. "Norman Thomas and the Struggle Against Japanese Internment." Prospects: An Annual of American Cultural Studies vol. 29 (2004): 419-434.

Shaffer, Robert. "Cracks in the Consensus: Defending the Rights of Japanese Americans During World War II." Radical History Review 72 (1998): 84-120.

Swanberg, W.A. Norman Thomas: The Last Idealist . New York: Scribner's, 1979.

Footnotes

- ↑ New York Times , June 19, 1942; 13:5

Last updated April 17, 2014, 9:49 p.m..

Media

Media