Japanese American Citizens League

The Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), formed in 1929, became the most well-known, influential Japanese American organization in the United States, but its history is not without controversy. The decision of the wartime JACL's leadership to cooperate with the federal government in the mass exclusion and incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II elicited harsh criticism from those who believed the organization should have done more to defend Japanese Americans' rights during the war. The JACL's wartime opposition of test cases and criticism of resisters and dissenters remains a painful source of division today. After the war, the JACL became active in turning back discriminatory legislation through the courts, lobbied for legislation that would allow greater rights for Japanese immigrants and subsequent generations of American citizens of various ethnic and racial backgrounds, and was a key player in the redress movement . Though still in existence today, the JACL has seen its influence and membership wane with the changing demographics and politics of the contemporary Asian American community.

Early History of the JACL

The JACL was formed as an umbrella organization that was composed of existing Nisei organizations in California and Washington, including the American Loyalty League, based in Fresno and led by Nisei dentist Thomas T. Yatabe; the Seattle Progressive Citizens League, led by newspaper publisher James Sakamoto ; and the San Francisco-based New American Citizens League, led by Nisei lawyer Saburo Kido . The JACL held its first national convention in Seattle in 1930. Despite much debate over the name, especially those who resisted inclusion of "Japanese" in the title, fearing that this would only raise doubts about the organization's loyalties, the newly formed Japanese American Citizens League adopted two initial goals. First they lobbied Congress to amend the Cable Act of 1922 that, among other provisions, stripped women of their citizenship if they married men ineligible for citizenship, or in other words if they married immigrants from Asia. Congress amended the Cable Act in 1931. Second, the JACL lobbied Congress to secure citizenship for veterans of the First World War. The campaign to lobby Congress was spearheaded personally by Tokutaro Slocum , an Issei veteran who encouraged the JACL to throw its weight, as young as the organization was, behind helping Issei veterans secure citizenship. Issei veterans were finally granted citizenship in 1935 when Congress passed and the president signed the Nye-Lea Act.

On a local level, chapters of the JACL held meetings that some dismissed as social events. These meetings were meant to bring Nisei together to discuss issues they shared in common and to raise Nisei political awareness. Local chapters encouraged Nisei to register to vote, and worked to foster Nisei awareness of their citizenship rights and responsibilities.

The JACL by definition was exclusive. It was an organization open only to citizens. Issei (with the exception of World War I veterans who had secured citizenship through the Nye-Lea Act) were automatically excluded from membership. Nisei sympathetic to labor interests, involved with the Young Democrats, or who were not interested in super-patriotism as their ticket to acceptance into mainstream American society found the JACL did little to address their needs or interests. The JACL never meant to represent the interests of the entire Nikkei community. It represented one current of Nisei thought and politics in the prewar years. Nisei organizations that existed outside the umbrella of the national JACL blossomed in the 1930s, but remained deeply divided over the direction Nisei leadership should take.

Wartime JACL

Staffing and Membership

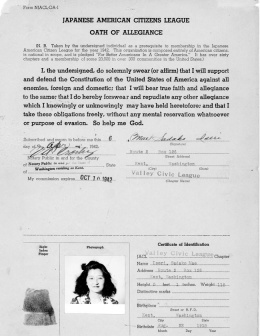

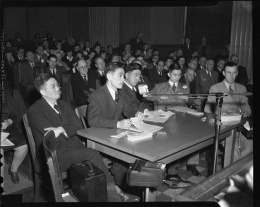

The JACL changed dramatically in 1941 due to the impending threat of war between the United States and Japan, and the new leadership of the organization. JACL President Saburo Kido and Executive Secretary Mike Masaoka launched an aggressive campaign to expand membership and improve the public image of the Nisei as loyal American citizens. Kido's decision to hire Masaoka as executive secretary had a particularly polarizing effect on the JACL membership. Since he had been hired for what was then the only full-time paid position with the national organization, the choice indicated a new wartime direction based on his peculiar notion of the position Nisei occupied and the burden that they carried to prove themselves loyal to the United States. He was charismatic and well-connected politically within certain circles, but he was not well connected within Japanese American communities. He grew up in Salt Lake City, was a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, otherwise known as the Mormons, where he had limited contact with other Japanese Americans and had developed an exaggerated notion of how far Nisei should go to prove their loyalty and their assimilation to American society. Masaoka embraced Americanization wholeheartedly. This attitude was reflected in the " Japanese American Creed ," which was written by Masaoka and promoted as evidence of Nisei loyalty to the United States despite the realities of racial discrimination. Kido and Masaoka included the "Japanese American Creed" in press releases and Togo Tanaka and Mike Masaoka read the creed when testifying before congressional committees in an effort to bolster a positive image of the Nisei and prevent restrictions on Nisei rights.

The JACL was already an exclusive organization created by and for citizen Nisei, but as war loomed, Masaoka encouraged the JACL leadership to disassociate themselves and the organization even further from Issei in an effort to defend themselves from ongoing accusations that Japanese Americans were divided in their loyalties between the United States and Japan due to their racial ancestry. As Paul Spickard noted, the public disavowals of the Issei made the JACL unpopular with the Issei leadership. [1]

One of Masaoka's goals as executive secretary was to increase JACL membership, however his efforts remained unsuccessful. Leading up to America's entry into World War II, membership remained relatively small. Citing Fred Tayama's reports on membership in the league's Southern District Council, Paul Spickard noted that even though 10,500 Nisei were registered to vote in the city of Los Angeles, and 12,300 were registered to vote in the county late in 1941, there were only 673 registered JACL members in the same area. Nationally, the JACL claimed that it had 20,000 members, but this was an exaggeration. Even though far fewer Nisei were dues-paying members than national JACL headquarters claimed (best estimates indicate that approximately 8,000 Nisei were members), this still indicates that a significant percentage of Nisei who were of age at the beginning of the war identified with the JACL in some way even if that percentage were limited to 10-20% of Nisei households. [2]

When the JACL was forced to close its offices in California, it relocated its national office to Salt Lake City, where the organization launched efforts to transform its newsletter into a full-fledged newspaper. Kido invited Larry and Guyo Tajiri to move to Salt Lake City in the spring of 1942 to edit and write The Pacific Citizen , and transform it into a full-fledged national newspaper. The Pacific Citizen covered stories of importance to Japanese Americans, and even though it was used in part as a propaganda campaign to repair the image of Japanese Americans and promote Japanese American patriotism, especially by highlighting the heroism of Japanese Americans in the military, the paper also reported on the court cases of individuals like Gordon Hirabayashi , Fred Korematsu , and Minoru Yasui and other stories of resistance, especially the draft resisters . The Friends of the American Way nominated the Pacific Citizen for a Pulitzer Prize in journalism in 1946. [3] The paper became an important record of the Japanese American wartime experience and continues to be an important, well-respected newspaper today.

Wartime Cooperation and Its Consequences

The JACL made decisions during World War II that drew harsh criticism from fellow Japanese Americans. Both before and after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor , the JACL collaborated with the U.S. government, FBI , and the Office of Naval Intelligence in an attempt to promote Nisei as loyal, patriotic citizens while at the same time helping to identify potentially disloyal Issei. [4] James Omura was not alone in criticizing the JACL for this decision, arguing that instead of defending Japanese Americans against unconstitutional violations of their civil rights, the JACL had sold Japanese Americans down the river in an effort to gain political acceptance and national influence. Over the summer and fall of 1942, the JACL lobbied the War Department to restore Japanese Americans' "rights" to be processed by Selective Service on the same basis as other Americans. A full restoration of Japanese Americans' rights to serve in the military, the JACL leadership argued, would allow Nisei to prove their loyalty and perhaps restore all Japanese Americans' rights in the process. This decision—made while Japanese Americans remained incarcerated in the custody of the War Relocation Authority —led to verbal attacks and even a few notorious physical attacks against prominent JACL leaders. For example, Saburo Kido was beaten in Poston , and Fred Tayama was beaten in Manzanar .

Opposing Dissidents

When military service was opened for Nisei volunteers in 1943 with the creation of an all-Nisei combat unit of the army (the 442nd Regimental Combat Team ), followed by a restoration of the draft for Nisei in 1944 to replenish the all-Nisei unit, the JACL urged cooperation and denounced those who resisted. The JACL criticized those who answered the loyalty questions with a " No-No " response during the registration crisis of 1943. The following year, when more than three hundred Nisei refused to appear for their pre-induction physicals, the JACL suggested that Nisei draft resisters be charged with sedition, not just Selective Service violations. In February 1946, the national board of the JACL met during the Ninth Biennial National Convention in Denver, Colorado, and discussed what position they would take regarding all those who had protested their wartime treatment, including those who had renounced their citizenship and requested repatriation to Japan, "No-No" resisters, and draft resisters. In response, the board formally condemned all of them, contributing to decades of marginalization for Japanese Americans segregated at Tule Lake , Nisei draft resisters, and others labeled "disloyal" for their wartime resistance. The decision to condemn resisters en masse reinforced the organization's decision four years previous to oppose any legal challenges that would result in test cases. JACL Bulletin No. 142, issued on April 7, 1942, stated that the national headquarters of the JACL was opposed to test cases that sought to determine the constitutionality of military regulations, such as curfew and exclusion from the West Coast. The decision, the bulletin explained, was unanimous. These two official positions taken by the JACL in addition to their support of intimidation campaigns within the camps to dissuade more Nisei from following the path of resistance left the organization vulnerable to criticism that it opposed and even ostracized those who took great risks in an attempt to clarify both Nisei citizenship rights and Issei civil rights in a time of war,

Other Wartime Actions

Even though debates over the JACL's wartime legacy tend to focus on its opposition to test cases, the draft resisters, and other forms of dissent, the organization was engaged in other activities that were designed to help Nikkei through the process of relocation. The JACL softened its initial opposition to any test cases when lawyers for the organization submitted an amicus brief on behalf of Fred Korematsu. His case challenged the constitutionality of his forced exclusion from the West Coast. The organization also sought ways to ease the resettlement process. It created a credit union in 1943 to provide loans to support Japanese American resettlement, and set up offices in Chicago to assist Japanese Americans relocating to the Midwest. The JACL encouraged families to write to hometown newspapers about the military service of their Nisei sons. Some criticized their use of Nisei casualties in West Coast newspapers as an inappropriate attempt to promote the public image of the JACL. The JACL leadership hoped that Americans who learned of the wartime sacrifices of Nisei troops would be more likely to accept Japanese Americans into their communities once the West Coast was opened up for Nikkei to return home.

Postwar JACL

After the war was over, lawyers and lobbyists for the JACL worked hard to overturn laws banning interracial marriage, segregation, restricted rights to citizenship, and immigration based on race. The JACL lobbied to end alien land laws in California, lobbied for passage of the Evacuation Claims Act , and for legislation that would end racial restrictions on naturalization. The McCarran-Walter Act , or the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 granted Issei the right to naturalized citizenship and ended the ban on immigration from Japan. JACL lawyers also wrote briefs in support of ending segregation in schools in the case of Brown v. Board of Education and in favor of ending restrictions against interracial marriage in the case of Loving v. Virginia .

One of the most enduring contributions the postwar JACL leadership had was on the historical memory of the meaning of Japanese Americans' incarceration during the war. Nisei had been traumatized by their characterization as suspect citizens during the war. Many responded by embracing the model-minority concept. Within the context of the cold war, memories of the extraordinary sacrifice of the segregated 442nd led to the commonly accepted myth that all Nisei veterans had volunteered for this dangerous call to duty (ignoring the involuntary draft that followed the initial voluntary recruitment in 1943). Portraying Nisei veterans as heroes who volunteered for duty heightened the image of their loyalty and their voluntary sacrifice in defense of their country. In this narrative, the contradictory story of draft resisters, "no-no" boys as they became known, and renunciants became victims of historical amnesia. Writers like Bill Hosokawa , a long time Pacific Citizen columnist and JACL in-house historian, played an important role in shaping historical memory of Japanese Americans' wartime experiences, first with the publication of his book, Nisei: The Quiet Americans , which highlights the loyalty of Nisei, their sacrifice on the battlefield, and the postwar upward mobility of "the quiet Americans," loyal to the end, epitomizing the image of a model minority.

In the 1970s, elements within the JACL began to push for individual monetary reparations for Japanese Americans incarcerated during the war. This stance initially divided the organization, with many key leaders opposing such reparations. The JACL's eventual decision to work with Japanese Americans in Congress to support the formation of a study commission—what would become the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC)—led to the splintering of the redress movement and the formation of two other national organizations that would pursue different paths. But after the CWRIC hearings and its 1983 report recommending that the United States government officially apologize for the wrongs committed and provide monetary restitution, the groups worked together in support of legislation towards that end. JACL lobbying and influence were key factors in the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 , passed by Congress and signed into law by President Ronald Reagan.

Two major questions emerged in the 1990s: To what extent did the JACL cooperate with the government during the war and should Japanese Americans recognize the draft resisters as defenders of civil rights? To answer the first question, the JACL commissioned its own study. In 1990, they hired historian Deborah K. Lim to investigate the history of JACL collaboration with the government during the war. The evidence Lim found was far more damning than the JACL had expected. She found that the JACL had done much more than cooperate. The JACL had not defended Nisei rights as the civil rights organization that it would become in the years following the war. After much debate, the JACL voted in 2000 to recognize and apologize to the Nisei "draft resisters of conscience" for the way they were treated during the war.

In 2002, the JACL held a public ceremony in which it recognized the Nisei draft resisters as "resisters of conscience," and apologized for its wartime condemnation of the draft resisters. It had taken decades for the JACL to resolve internal conflicts over whether or not it should apologize as an organization for its wartime marginalization of the resisters. During the ceremony, Frank Emi asked that the JACL go a little bit further and apologize to all Japanese Americans for the decision the wartime JACL made to denounce all who resisted the government's unconstitutional wartime policies and for the leadership's decision to cooperate with the wartime exclusion and incarceration of 120,000 Nikkei without due process. Even with the apology to Nisei draft resisters in May 2002, old scars continue to haunt others who were labeled "disloyal" during the war, and debates still rage over what responsibility the JACL has in healing those wounds.

Today, the JACL works hard to live up to its highest goals of being a civil rights organization committed to defending the rights of all Americans, not just citizens of Japanese ancestry. The JACL strongly supports Japanese American National Museum programming that addresses the "happa" identities of the youngest generations of Japanese Americans, and the younger generations of JACL leadership have taken steps to repair the divisions created during the war years over issues of who could or who could not be considered a "loyal" American. The JACL has become strongly supportive of equal marriage rights for all, including same-sex couples as an example of their expanding notion of their role as a civil rights organization.

For More Information

Hosokawa, Bill. Nisei: The Quiet Americans . 1969. Revised Edition. Denver: University Press of Colorado, 2002.

JACL homepage, http://www.jacl.org/ .

Lim Report, http://www.resisters.com/study/LimTOC.htm .

Lyon, Cherstin. Prisons and Patriots: Japanese American Wartime Citizenship, Civil Disobedience, and Historical Memory . Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011.

Murray, Alice Yang. Historical Memories of the Japanese American Internment and the Struggle for Redress . Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008.

Pacific Citizen , http://pacificcitizen.org/ .

Robinson, Greg. Pacific Citizens: Larry and Guyo Tajiri and Japanese American Journalism in the World War II Era . Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012.

Shimabukuro, Robert Sadamu. Born in Seattle: The Campaign for Japanese American Redress . Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001.

Spickard, Paul R. "The Nisei Assume Power: The Japanese [American] Citizens League, 1941-1942." Pacific Historical Review 52, No. 2 (May 1983): 147-174.

Takahashi, Jere. Nisei/Sansei: Shifting Japanese American Identities and Politics . Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1997.

Wu, Ellen D. The Color of Success: Asian Americans and the Origins of the Model Minority . Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014.

Footnotes

- ↑ Paul Spickard, "The Nisei Assume Power: The Japanese Citizens League, 1941-1942," Pacific Historical Review 52, no. 2 (May 1983): 155.

- ↑ Spickard, 156. Paul Spickard and Togo Tanaka cite the 8,000 figure to make the point that JACL exaggerated its membership. But this figure seems to undermine their point that membership in JACL was limited. While there may have been 80,000 Nisei living on the West Coast at the beginning of the war, only about half were adults in 1941 and a good percentage of the adults were married to each other. So the number of Nisei households is probably closer to 35,000 of which 8,000 represents a significant percentage.

- ↑ Lynda Lin, "Celebrating the Pacific Citizen's 80-year Legacy," Pacific Citizen, January 27, 2009, accessed November 15, 2012, http://www.pacificcitizen.org/node/173?page=show .

- ↑ Spickard, 157.

Last updated Oct. 8, 2020, 4:12 p.m..

Media

Media